- Home

- >

- Preservation Archaeology Blog

- >

- Tracking Kayenta, Understanding Salado

|

By Jeff Clark, Preservation Archaeologist

|

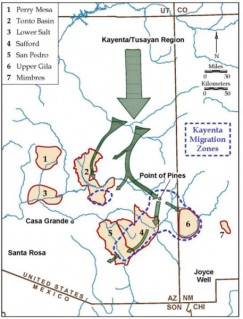

Our work in Mule Creek and the Upper Gila is part of Archaeology Southwest’s long-term research project to assess the scale and impact of Kayenta migrations in the southern Arizona during the late 13th and 14th centuries A.D. The Kayenta were a relatively small “group of groups” that substantially influenced much larger local populations everywhere they moved. Archaeology Southwest research has emphasized the persistence of Kayenta identity and the role these immigrants played in generating what archaeologists have labeled the “Salado.”

During the 75 years since its inception, the Salado has been called just about everything: a culture, a religion, an elite group, a phenomenon, and merely a question. Defining Salado has been just about as hard for archaeologists as defining Chaco. Our research has led us to believe the Salado was an inclusive ideology that integrated Kayenta descendants and various local groups in the valleys where they resettled. Integration and frequent interaction ultimately led to some degree of cultural hybridization, although earlier identities persisted. For example, just as someone living in the USA can be both American and Anglo-Saxon, Jewish, Arab, or Irish, we believe that the ancient inhabitants of the southern Southwest could be both Salado and Kayenta, Hohokam, or Mogollon (or their indigenous equivalents).

From 1990 through 2007, Archaeology Southwest conducted valley-by-valley research throughout southern and central Arizona. In 2008, we decided to hop across the border into New Mexico because we believed some of the last Salado communities were along the Upper Gila and its tributaries. Using the X-Ray Fluorescence Lab at the University of California at Berkeley we also determined that many Kayenta enclaves and subsequent Salado settlements in southern Arizona were consuming obsidian from the Mule Creek area of New Mexico instead of using closer sources.

In conjunction with Hendrix College, our excavations at the 3-Up site at Mule Creek during the summers of 2008 and 2009 identified a potential Kayenta enclave just outside the main occupation. Locally produced Maverick Mountain series pottery, a telltale indicator of the presence of Kayenta groups, was found in prodigious quantities at this enclave and was also common in other portions of the site. The 3-Up site developed into a large Salado village during the 1300s that may have endured well into the 1400s. 3-Up is, literally, on top of the Mule Creek obsidian source, and our test units unearthed large quantities of obsidian tools and manufacturing debris. Hence, we believe we have found our supplier. Rob Jones will have more to say about this in a future blog.

During the past two years, we have focused our attention at Fornholt, the other major 13th century site in the Mule Creek area identified to date. Our work at Fornholt has been discussed in previous blogs by Deb Huntley, Katherine Dungan, Rob, and various students. What I find so fascinating about Fornholt is that the site was occupied at least until A.D. 1300 and perhaps a bit longer based on the ceramic types recovered from our test excavations. Thus, Fornholt was inhabited at least a generation after Kayenta immigrants arrived at 3-Up.

Our excavations at both sites reveal that their inhabitants were involved in similar decorated ceramic exchange networks, with one notable exception: not a single Maverick Mountain or Salado polychrome sherd has been recovered from Fornholt, despite the fact that both ceramics were locally produced in the valley—probably at 3-Up, considering the high frequencies there. To me, this suggests that tension existed between the two settlements, especially after the arrival of the Kayenta.

How this tension was resolved is still unclear. However, several facts are clear: Fornholt was depopulated by A.D. 1325, while 3-Up lasted a century longer. In addition, portions of Fornholt burned near the time of its abandonment, including one storage room filled with hundreds of maize cobs. If other storage rooms were also burned, the occupants would have been hard pressed to feed themselves until the next harvest. Determining the fate of Fornholt will be one research objective that will guide our work next year.

Explore the News

-

Join Today

Keep up with the latest discoveries in southwestern archaeology. Join today, and receive Archaeology Southwest Magazine, among other member benefits.

4 thoughts on “Tracking Kayenta, Understanding Salado”

Comments are closed.