- Home

- >

- Preservation Archaeology Blog

- >

- Talking Turkey: Unexpected Encounters with New Wor...

|

By Katherine A. Dungan, Research Assistant

|

With Thanksgiving nearly upon us, we thought that it would be fun to share with our readers our own memorable turkey experience, as captured on film when we were recording Archaeology Southwest’s Mule Creek videos. But first, a bit of background on turkeys and their role in the prehistoric Southwest:

(November 23, 2011)—Although other New World domesticates often appear in Thanksgiving dinners—maize might make an appearance of one kind or another, and squash (or at least one type of squash) is likely to show up as pumpkin pie during dessert—nothing symbolizes Thanksgiving quite so much as the turkey. Modern domestic turkeys are descended from birds domesticated in Mexico, meaning that your Thanksgiving turkey is more closely related to birds that were served up in the Aztec capital of Tenochtitlan than to birds you might see in your backyard somewhere in the United States.

In the Southwest, domestic turkeys may have been present as early as the last centuries BCE or early centuries CE. Evidence for domestic turkeys, including droppings, eggshell, and feathers, has been found at Basketmaker III sites in the northern Southwest, and, by the protohistoric period, turkey pens were in use at Paquimé in northern Chihuahua and at sites scattered throughout the Puebloan Southwest. In Mule Creek, we have a small amount of turkey bone from 3-Up, the only site for which we have a complete faunal analysis of our excavated material.

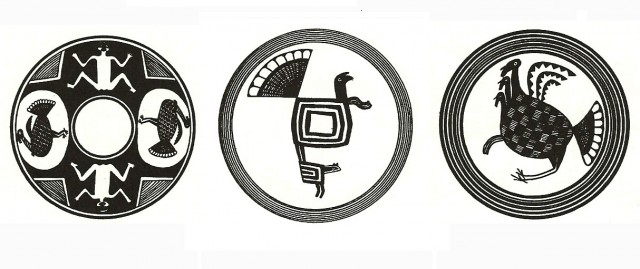

Although we think of turkeys primarily as food animals, prehispanic Southwestern people may have valued turkeys largely for their feathers, which were used in the creation of ritual objects and more mundane items, including textiles. Charmion McKusick has argued for the importance of turkeys as ritual sacrifices, perhaps associated with Mesoamerican rain deities.

Recent research suggests that, unlike maize, domestic turkeys were not initially brought into the Southwest from central Mexico, however. In a genetic study published last year in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Science, it was determined that most archaeological Southwestern turkey remains were more closely related to birds living today in the eastern U.S. and northeast Mexico than to central Mexican or modern domestic turkeys. This suggests that domestication of turkeys also took place outside of Mesoamerica, though not necessarily in the Southwest.

A final point to consider as you watch the cheerful turkey-shaped balloons in the Macy’s parade: turkeys have a belligerent streak, as well. Among native groups in the southeastern U.S., turkeys were specifically associated with warfare. After meeting the turkeys in the video, I can see why.

For more information on birds in the prehispanic Southwest, check out this past issue of Archaeology Southwest Magazine. Information for this post was drawn from the following sources: Hudson, C. 1976 The Southeastern Indians. U. of Tennessee Press; McKusick, C. 2001. Birds of Sacrifice. Arizona Archaeologist No. 31. Arizona Archaeological Society; Munro, N. 2006. The role of turkeys in the Southwest. In the Handbook of North American Indians, Vol. 3, Environment, Origins and Populations, ed. W. Sturtevant, pp. 463–470. Smithsonian; Speller, C. et al. 2010. Ancient mitochondrial DNA analysis reveals complexity of indigenous North American turkey domestication. PNAS 107(7):2807–2812. Any mistakes in data or interpretation are mine.