- Home

- >

- Preservation Archaeology Blog

- >

- Salado polychrome pottery, part 1

|

By Deborah L. Huntley, Preservation Archaeologist

|

A major part of our research at Mule Creek—and in the Upper Gila region in general—is to identify compositional and stylistic variability in Salado polychrome pottery (also known as Roosevelt Red Ware) through time and across space. Identifying compositional variability means looking at what the pottery is made of, what materials were used. Stylistic variability has to do with what the pottery looks like, how it is decorated.

We are using these data to track processes of migration, population coalescence, and long-distance interaction in the study area. In the context of our work in the American Southwest, coalescence refers to the process of combining social groups from diverse backgrounds into large, multiethnic communities. This occurred after A.D. 1300.

Since I’m working on a poster presenting this analysis at the upcoming meeting of the Society for American Archaeology in Memphis, I thought I would talk a little bit about the preliminary results of our typological and stylistic studies. Today I’ll address typology; next week, style.

Salado polychromes are a general class of pottery known as a ware, which means they are made using similar raw materials and share many aspects of technology and style. Archaeologists have traditionally divided Salado polychromes into three main types—Pinto, Gila, and Tonto—based mainly on their design configurations. Pinto Polychrome was the earliest type made (from about A.D. 1280 to 1330), followed by Gila Polychrome (from about 1300 to 1450) and Tonto Polychrome (from about 1350 to 1450). In addition to different date ranges for their manufacture, each type seems to have somewhat different spatial distributions.

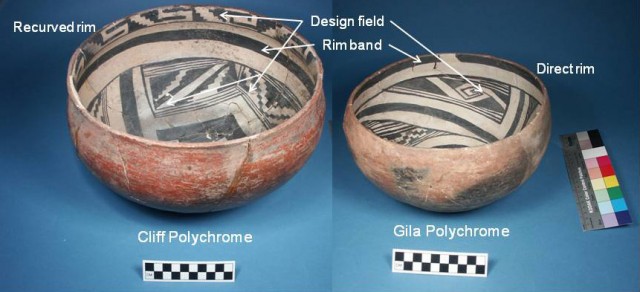

Archaeologist Patrick Lyons recently examined variability within Salado polychromes and argued that late versions of this ware can be split into several distinctive types based on their stylistic and morphological characteristics. One of these types, Cliff Polychrome, would have been lumped with Gila Polychrome under the traditional typology. Cliff Polychrome only occurs in bowl forms, almost always has a recurved rim, and differs from Gila Polychrome in that it has a dual design field, with one design above and one design below the rim banding line. Gila Polychrome bowls typically have direct rims and a single design field below a rim band.

The other newly defined late types overlap quite a bit with Tonto Polychrome, but have additional distinctive attributes, such as a smudged (blackened and polished) interior surface. Archaeology Southwest’s previous research in the San Pedro Valley and elsewhere suggests that these types were among the latest Salado polychromes to be made, well into the 15th century, and that they were associated with some of the latest occupied coalescent communities in the southern Southwest.

In the Upper Gila region, we are finding some variability in Salado polychrome types among different river drainages. For example, Gila, Tonto, and Cliff Polychrome are found at nearly every post-1300 site in our study area, including the Mimbres Valley. Other late types like Dinwiddie Polychrome (see below) are common in the assemblages from sites like 3-Up in Mule Creek, Ormand Village in the Cliff Valley, and Buena Vista/Curtis in the Safford Basin, but are absent in our sample of Mimbres Valley Salado site components.

Does this mean that Mimbres Valley potters were somewhat isolated from later developments in Salado polychrome style? Or were the Mimbres Valley sites abandoned prior to the 15th century, when many of the latest Salado polychrome types were being made? We are still investigating these questions.