- Home

- >

- Preservation Archaeology Blog

- >

- Pretty Rock: Creating Virtual Interactive Models o...

Things have been quiet on the Virtual Southwest project as we fine-tune our models and programming, so I thought I’d take a moment to share a bit about some new tools for documenting and sharing archaeological landscapes that we are utilizing in an upcoming exhibit called Chaco’s Legacy. Fellow digital archaeologists should note that most of the tools and techniques demonstrated in this blog are available for free or for fairly low cost to educational and nonprofit digital archaeologists.

As work continued on the Chaco’s Legacy project, we ran into a problem with the modeling of the canyon itself. We were using a standard terrain model created by digitizing USGS topography and draping satellite images as texture maps on to the resulting mesh. This technique looks great from a distance, but when you “went inside” the virtual world, the sharp and angular cliff faces of Chaco Canyon looked as if they were “smeared,” with the sharp sandstone cliff faces looking like melted blobs of wax.

At about this time, we began to see amazing results generated in Agisoft’s Photoscan software—and we were not alone. Almost every digital archaeology presentation at this year’s meetings of the Society for American Archaeology featured geometry and texture maps created by this new tool for photogrammetric modeling. By generating terrain models from oblique aerial photography, Photoscan offered the opportunity to create models of canyon geometry with textured surfaces that would more accurately portray the canyon’s surfaces.

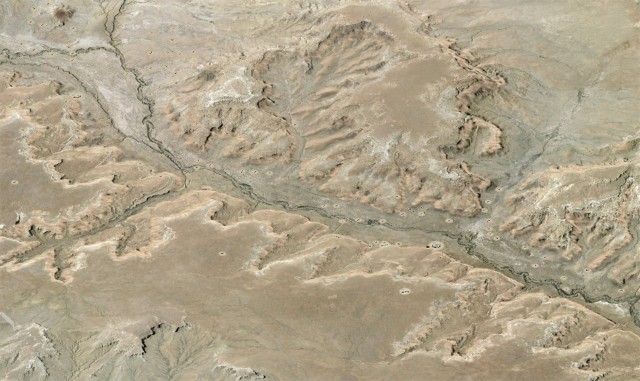

The next question was how to get low-level oblique and zenoidal (top-down) aerial photography of Chaco Canyon? At first, we toyed with the idea of using an Unmanned Aerial Vehicle, but we found this to be impractical, and actually illegal in the United States. Fortunately, we were already working with Adriel Heisey, a world-renowned aerial photographer whose artistry has been featured in museum exhibits, books, and the pages of National Geographic. Adriel was willing to try collecting the images, but we needed a test case to be sure that our investment in his time would produce useful results. Adriel chose the ancient Chacoan shrine at Pretty Rock as a test case. Situated atop a steep sandstone butte in northwestern New Mexico, the shrine at Pretty Rock turned out to be an ideal test case for our modeling problem.

We were unsure of the number of images we would need for the modeling process, so we decided to use still frames from a high-definition video camera at 1080p resolution. The video above is a segment of the raw video that was recorded by Adriel’s steady hands as he piloted his specially modified aircraft with his legs. No on-camera or post-processing stabilization was utilized for this footage.

The 1 minute and 28 seconds of uncompressed digital video were delivered by YouSendIt, and video-editing software was used to extract TIFF files at one frame per second from the footage. The video frames were examined individually, and anything that would interfere with the modeling process (such as the aircraft’s shadow, or frames where the wing or landing gear was visible) were masked using an Alpha Channel. The TIFF files were loaded into Photoscan, and digital modeling began.

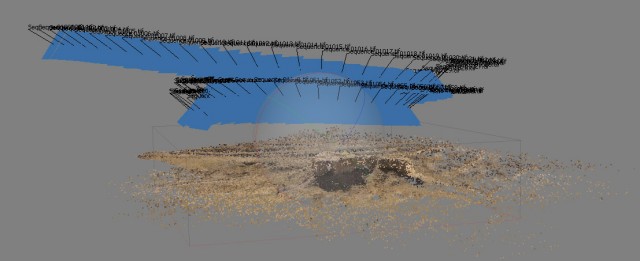

The first step in this process within Photoscan was to load a calibration file for the specific camera lens and focal length used. Once all of the images were calibrated and the masks were extracted from the TIFFs, the software began the modeling process by aligning all of the cameras into spatial relationships with each other. It then generated a cloud of data points found to be in common between pairs of images. The resulting point cloud is displayed in the image below.

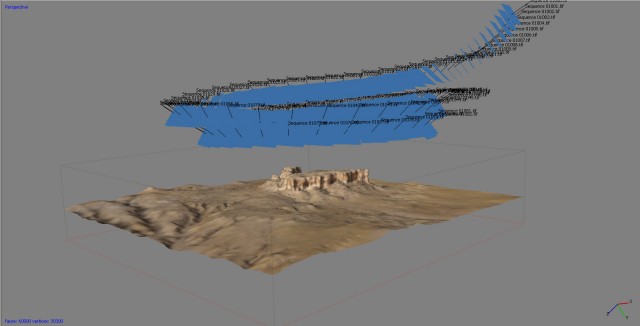

The blue squares intersected by the black lines are the depictions of each individual camera in relation to the geometry being modeled. The position and spatial orientation of each camera is recorded in three-dimensional space. My fellow three-dimensional modelers will recognize immediately that this is a fantastic feature, because it enables precision camera-mapping and a variety of interesting modeling possibilities.

The next step was to examine the point cloud for erroneous points, because statistical modeling techniques will often generate these errors as a type of digital noise. In this case, though, the model was fairly clean, with only a few errant points and no misaligned images that needed to be removed.

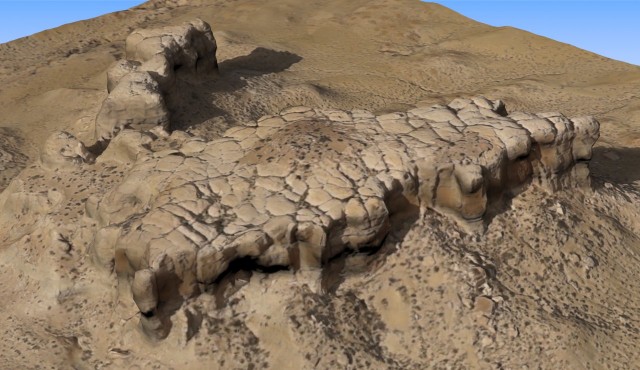

Once the point cloud was ready to go, a surface model was generated. Photoscan provides numerous options for processing models, but I was in a hurry, so I selected a smooth model at medium quality. The resulting geometry is shown in the figure above.

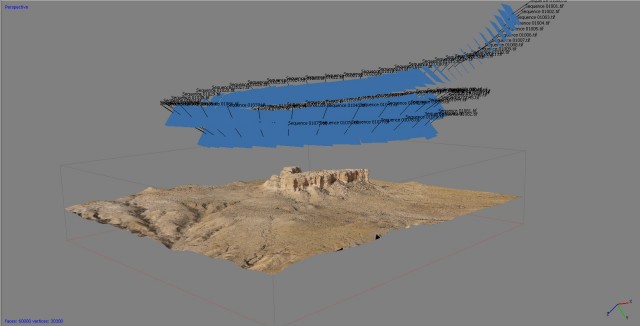

The next stage of the process was to develop the photographic texture map. The colors on the surface model above were based upon loose averages of the color values assigned to the data in the point cloud (a.k.a. vertex color), so one final step was needed to generate the photorealistic image that would be mapped onto the surface geometry. Photoscan creates such a mosaic graphic from an analysis of the digital stills used to create the geometry. I wanted a very high-resolution texture map for the demonstration, so I went with a 4096 * 4096 pixel map, generated in the adaptive orthophoto mode to provide the best image mapping on the vertical cliff faces.

Once this result had been generated, I was very confident in being able to utilize this type of aerial photography to model the cliffs at Chaco. But what about the archaeology? At this point, I went ahead and exported the model as an FBX file and “fed” the model into our 3D renderer to get a better look. In the image below, you can see the circular feature of the ancient Chacoan shrine that sits atop Pretty Rock.

At this point, I could not resist animating a fly-around, so I used my trusty copy of 3D Studio Max to generate a quick 600 frames.

Up until a couple of years ago, this was where I would stop. With the model constructed and animation rendered, I would put it online or in a kiosk and move on to the next task. But now that we have middle-range game engines, it was a trivial task to import the model into Unity 3D, add a first-person-perspective controller and “skybox” background, hit play, and voila! Instant first-person simulation of an ancient archaeological landscape. And once that was done, it was even easier to export the simulation space as applications in multiple formats:

Explore Pretty Rock via the Web – Requires the Unity 3D Plugin

Download the simulation for Windows (9 mb)

Download the simulation for Windows with the Oculous Rift Display (9 mb)

Download the simulation for Macintosh (Bug found, fixed version coming soon.)

Download the simulation for Linux (13 mb)

With the model done and a simple simulation space completed, it was clear to me that Photoscan is an amazingly capable modeling system that has the capacity to change archaeological practice in ways we can only begin to imagine. To provide a single example of my definition of “amazing,” perhaps the most astonishing aspect of this entire test project was the time it took to complete the effort. From the arrival of the video file on my desktop, through the creation of the textured model, the rendering of the animation, and the completion of the virtual first-person simulation, the total project time was four hours. It took three times that amount of time just to post the demonstration files and then write and format this blog post.

Interested in building your own virtual simulation? Just try it! The Unity 3D “Indie” version is free to use for just about everything except for advanced lighting and water effects. To get up to speed on how to use Unity to construct first-person perspective environments, spend a morning with this set of tutorials from 3dBuzz. If you would like to follow along and explore building a Unity simulation space of Pretty Rock on your own, feel free to download the source files here, and see the Readme.txt file for a couple of pointers on keeping your application’s users from falling off the edge of your virtual world.

And so with our methodology proven, its time to model all 7 miles of downtown Chaco Canyon—four time periods, six great houses and 100 small house sites, all to be rendered in real time. But before we explore Chaco’s Legacy, my next post will look at the good, the bad and illegal sides of using drones for aerial photography.

6 thoughts on “Pretty Rock: Creating Virtual Interactive Models of Places of the Past”

Comments are closed.

Explore the News

-

Join Today

Keep up with the latest discoveries in southwestern archaeology. Join today, and receive Archaeology Southwest Magazine, among other member benefits.

Looks cool, would like to try it outt, but neither of the Windows download links are working, nor is the source files link.

Try again. I accidentally posted Rars instead of the Zips I was coding for.

Mac simulation not running, and source files link broken.

See http://www.rupestrian.com/quadcopter.html

Hopefully, FAA rules will change soon, if the government shutdown ever ends.

Sorry Mark,

I don’t know why the Mac export is failing, looking into it now.

Thanks – Windows plain and source files are now working. Oculous file is still missing, but since I don’t own one, I can live with that.

Doug,

Nice work! Thanks for the making the source files available.