- Home

- >

- Preservation Archaeology Blog

- >

- Student Research at the Dinwiddie Site: Raw Materi...

Students attending the 2013 Archaeology Southwest/University of Arizona Preservation Archaeology Field School completed several interesting and valuable research projects covering a wide range of topics, from experimental ceramics and flaked stone studies to magnetometer surveys. A course requirement, these projects contribute to our long-term research in the Upper Gila region of southwestern New Mexico. This is the first in a series of blog posts highlighting student research.

Robbie Grenda, Emily Reed, Heather Seltzer, and Jay Stephens collaborated on a project designed to identify potential sources for some of the raw materials used by residents of the Dinwiddie site. The group focused on four material classes: turquoise, shell, obsidian, and ceramic raw materials. Students reviewed the possible uses of these materials to produce ornaments and tools, their relative abundance and distribution on the landscape, and possible avenues for their procurement.

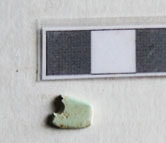

We found shell and turquoise in small amounts in our test units this summer. Turquoise is one of several blue-green minerals valued by many precontact residents of the Southwest (the people who were living here before Europeans arrived). It occurs in several areas of Arizona and New Mexico; perhaps the best-known source is the Cerrillos Hills mines near Santa Fe. The turquoise source nearest the Dinwiddie site is in the Burro Mountains, about 40 kilometers to the southeast, and other known sources are several hundred kilometers away. Isotopic sourcing would help us pinpoint which sources Dinwiddie residents used, thus enabling us to reconstruct trade patterns.

In precontact times, people used shell mostly for ornaments such as pendants and bracelets. We found three marine shell ornaments at Dinwiddie this summer: two whole Olivella beads and one worked Haliotis fragment. These materials came from the California Coast or the Gulf of California. (Chris Lange of Desert Archaeology, Inc. identified the species.) In addition, we found several fragmentary freshwater Anodonta shell fragments, which could have come from nearby Duck Creek or from the Upper Gila River.

Obsidian is abundant at Dinwiddie, as it is on many Salado sites in southwestern New Mexico and southeastern Arizona. Within the Dinwiddie assemblage, there are formal tools—bifaces, projectile points, and so on—as well as obsidian debitage. The two major obsidian sources for the Upper Gila region are Mule Creek and Cow Canyon, both about a day’s journey from Dinwiddie by foot; farther away and to the south is another prominent source at Antelope Wells, a two-day journey. Flaked stone analysis and obsidian sourcing are in progress and should provide more information about lithic material procurement and use at Dinwiddie.

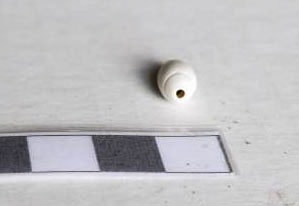

Finally, the group identified possible sources for raw materials used in pottery production at Dinwiddie. Previous clay compositional and petrographic studies have determined that potters from Dinwiddie and other Upper Gila region villages made plain brown utility ware vessels and decorated Salado polychrome vessels. Dinwiddie residents probably also acquired some decorated pottery through trade with contacts in the surrounding region and beyond. Although pottery clays and sand temper were readily available in nearby Duck Creek or along the Upper Gila, obtaining pigments for red and white slips and black paints would have required traveling longer distances. Dinwiddie potters could have found manganese, hematite, and kaolin minerals within a two-day walk from the village.

Explore the News

-

Join Today

Keep up with the latest discoveries in southwestern archaeology. Join today, and receive Archaeology Southwest Magazine, among other member benefits.