- Home

- >

- Preservation Archaeology Blog

- >

- This Post Is Not about the Borg or Peanut-Butter C...

(November 4, 2013)—One of the most rewarding aspects of serving as the content editor of Archaeology Southwest Magazine is the continual opportunity to learn new things directly from the finest scholars. I have been fortunate to have Tobi Taylor, the previous content editor, and Emilee Mead, publications director, as my mentors. With their guidance, and Bill Doelle’s, I’ve gotten braver about asking issue editors and article authors the kinds of questions I feel our readers and members might ask.

Back in August, Jeff Dean, Jeff Clark, Bill Doelle, graphics expert Catherine Gilman, and I met around our library conference table, brainstorming illustration concepts and asking each other questions that helped hone our presentation of Archaeology Southwest Magazine 27:3, “Before the Great Departure: The Kayenta in Their Homeland,” just released today. (That is to say, Jeff Clark, Bill, Catherine, and I asked Jeff Dean, the expert on Kayenta, many questions—and he was patient and gracious with his answers.)

After that meeting, I still had follow-up questions for Jeff Clark. Much of his recent research has examined Kayenta migration and Salado formation through the interpretive lens of diaspora (exile from one’s homeland, dispersal, and subsequent maintenance of a strong cultural identity across generations). As a proud Irish American from the south side of Chicago (with roots in Galway, Tuam, and Cork), this aspect of Jeff’s work resonates with me—even though the precontact Southwest was obviously a very different world from the one in which my great-grandparents emigrated. In working on this issue of the magazine, I found that Kayentans’ maintenance of a strong identity outside of their homeland didn’t surprise me at all; what I did find interesting was the apparent assimilation of other groups who left the Four Corners region in the late 1200s.

Jeff Clark was kind enough to respond most thoughtfully to my questions in this regard. Here is our discussion, conducted mostly by email:

Kate: Jeff, whenever I’m working on content with you and I come across the word “assimilate,” the cube comes into view, and I think, “Borg.”

Jeff C.: But there’s something to that! The Borg model was one of assimilative homogeneity. By contrast, the United Federation of Planets was based on inclusive diversity. This actually touches on Lewis [Borck]’s work in Social Network Analysis: homophily versus heterophily.

Kate: Jeff! Jargon.

Jeff C.: Homophily—love of the same, birds of a feather. Heterophily—love of diversity, opposites attract.

Kate: Gotchya. So, did “Kayentans” assimilate more so among “Tusayans,” to whom they were already relatively socially close?

Jeff C.: I think so. Here it would have been much easier to assimilate or hybridize (adopt characteristics of both groups) than in the south, because they did have existing close ties. In the south, because the Kayenta and Hohokam groups were socially distant, hybridization was difficult, and a new, transcendent ideology was required (or else conflict was likely). In this “heterophilic” ideology, you could retain your old Kayenta or Hohokam identity while participating in a new, inclusive Salado religion.

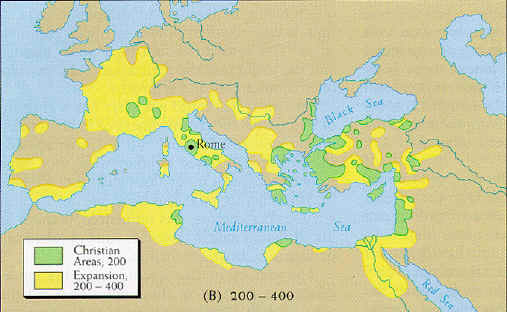

I feel that this is loosely analogous to early Christianity, which started out as a Jewish sect at a time of crisis in the Roman Empire and quickly spread to Egypt, Anatolia, and Greece—baptism meant you were included in something bigger than your specific heritage. Even though I’m not particularly religious, I did study the Bible as a historical document when I was a Southwest Asian archaeologist. Thinking of Salado, I am reminded of Galatians 3: 26–29, “There is neither Jew nor Greek, there is neither bond nor free, there is neither male nor female: for ye are all one in Christ Jesus.” I interpret this passage more figuratively than literally, with early Christianity transcending rather than negating these basic social divisions. This was a radical new way of thinking at the time. The ideology of exclusion laid out in the Hebrew Bible or Old Testament rapidly morphed into an ideology of inclusion in the New Testament. From its humble origins in a disadvantaged minority, Christianity replaced Roman religion and integrated the territory of the Roman Empire long after the fall of Rome.

Kate: The Federation transcendent! By the same token, then, did “Mesa Verdeans” (MVers) assimilate more readily because they joined groups they were already socially close to?

Jeff C.: That is a good point. MVers were socially and materially closer to Northern Rio Grande-ers than Kayenta were to Hohokam. This may have allowed them to fit in more easily. However, it is interesting that almost no distinctive MV traits survived the trip; they seem to have largely assimilated rather than hybridized. Many of these distinctive markers are ideological, so the disintegration of MV religion would account for much of their archaeological disappearance. Organic black paint ceramics and perhaps a certain MV architectural style (McElmo) survived in some places. It is hotly contested whether these are really markers of MV people, though. Finally, as we discuss in this issue, if MV social organization was more rigid than Kayenta social organization, then when that broke down in the homeland, it would have been hard to reconstitute elsewhere.

I think of Kayenta as peanut butter and MV as peanut brittle. If Hohokam is chocolate, then that makes Salado a Reese’s peanut-butter cup.

Kate: Ha! I’m wondering if that’s part of the answer to my [earlier, verbal] question about what researchers may have determined are the qualities of groups who assimilate quickly. Maybe it’s about the qualities of the hosts relative to the newcomers—maybe there’s not much assimilation to be done?

Jeff C.: I agree. The organization, size, and social distance of the host population have to be given equal consideration as that of the immigrants. Here, I think we have placed a bit too much emphasis on researching the Kayenta immigrant minority at the expense of the local majority. It is interesting that the Kayenta arrived in the south when the region was in an ideological void (Hohokam ballcourts long gone, buff ware and cremation burial complex in decline, platform mounds just starting to be built). Perhaps they arrived at a fortuitous time to start a new ideological movement. It is interesting that, analogous to early Christianity, Salado ideology started at the edges of the Hohokam World and worked its way toward the center over time.

Kate: Jeff, we should post this to the blog…

3 thoughts on “This Post Is Not about the Borg or Peanut-Butter Cups—Or Is It?”

Comments are closed.

One factor in this migration/assimilation equation that archaeologists necessarily ignore is that of language. With the Hohokam and Kayenta, for example, both of their possible descendants, the O’odham and Hopi, are Uto-Aztecan speakers. If there was some mutual intelligibility, that might have provided a point on entry and perhaps even some cultural affinity that affected social relations. I have long marveled at the linguistic diversity of Puebloan people that can be superficially viewed as sharing many cultural aspects. To me this indicates that many distinctly different people came to adopt similar behaviors and practices, yet refused to surrender their language. From a slightly different perspective, two groups of people bound by a similar language might find it more comfortable to share ideology.

Excellent point, Bruce–and one that Jeff Dean raised in conversation, but we didn’t end up discussing in the magazine. I’m glad you raise it here for further discussion.

I miss those little clay tablets we used to find in Mesopotamia that told us who spoke what where. We can only guess in the Southwest.

I wonder how different Kayenta language was from that of the people they encountered in southern Arizona. By A.D. 1275, the groups would have had little contact for at least a millennium and probably much longer. So the difference would have been beyond the dialect stage and perhaps more like German and English. Makes me want to read a comparison of Hopi and O’odham languages.