- Home

- >

- Preservation Archaeology Blog

- >

- Back to Basics, Part 2: Archaeological Cultures in...

On Monday, I wrote about how archaeologists define culture areas, which represent geographic zones in which people were living in generally similar ways and across which people were connected through shared history and practices. Before we look at the three main culture areas of the Southwest, I should say a bit about the earliest lifeways in the region.

The oldest archaeological remains documented in this region date to the end of the last Ice Age, about 13,500 years ago. We refer to these extremely mobile gatherers and big-game hunters (“big” as in mammoths!) as Paleoindians. “Clovis” is the name for the earliest well-documented manifestation of this pattern, though people may have been in the Southwest prior to what we recognize as the Clovis pattern.

Archaeologists recognize a widespread pattern, which we call Archaic, after the end of the last Ice Age. People hunted bison and other, smaller animals and gathered an ever-increasing diversity of plant resources. Interestingly, archaeologists use the Paleoindian, Clovis, and Archaic archaeological cultural designations across much of North America (though timing and some of the specifics may differ), suggesting that the ways in which these early populations lived were similar across a vast area. The high degree of mobility that marked the lives of early residents of the Southwest probably accounts, in large part, for the broad geographic scale of the similarities researchers have documented.

A little more than 4,000 years ago, maize (corn) agriculture arrived on the scene in the Southwest. Soon thereafter, people in some parts of the Southwest began to construct irrigation canals and establish increasingly permanent settlements. Throughout this process of “settling in” across the landscape, the ways people lived and the things they made and built began to diverge.

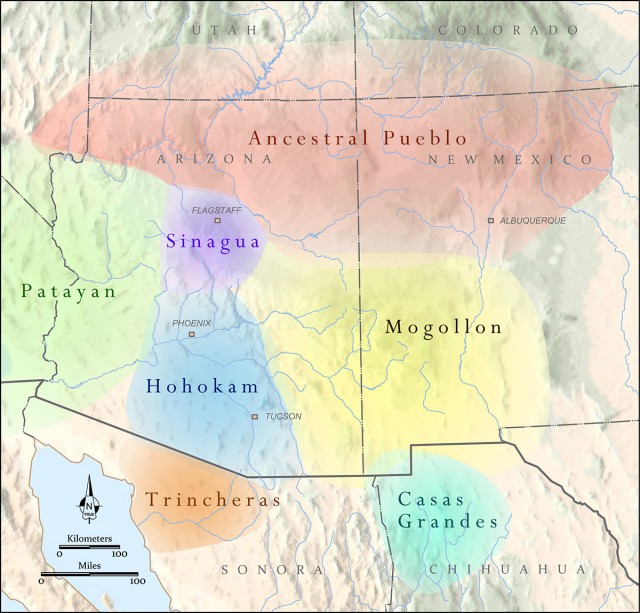

By about 2,000 years ago—and probably even a bit earlier—there were clear regional differences across the Southwest, and archaeologists have used evidence of those differences to define archaeological culture areas. The largest and best-known culture areas in the Southwest include the Ancestral Pueblo, the Mogollon, and the Hohokam. All of these groups were settled farmers, but there are key differences.

The Ancestral Pueblo (previously called Anasazi) region falls largely along the Colorado Plateau in the northern half of the Southwest. Most archaeologists have ceased using “Anasazi” because many contemporary Pueblo people oppose the term. As the name “Ancestral Pueblo” suggests, people in this region were among the ancestors of today’s Pueblo people.

At the earliest Ancestral Pueblo sites, people dwelled in deep pithouses (subterranean structures with a wood and earth superstructure) with roof entryways. These villagers made gray ware pottery (referring to the color of the clay) and beautifully woven baskets and sandals. To form vessels, potters in the Ancestral Pueblo region built up coils of clay and then scraped them smooth, which we call the coil-and-scrape technique—an uncharacteristically straightforward term borrowed from contemporary ceramic artists.

Later in time, people in the Ancestral Pueblo region began to build aboveground stone-masonry structures (commonly known as pueblos), and they commenced making beautiful black-on-white, red, and multicolored (polychrome) pottery. People in this region also built large structures that they probably used for religious observances. Archaeologists call the most common forms of these structures great houses (large and impressively built pueblos) and great kivas (round, semi-subterranean structures used as spaces for religious purposes or other large gatherings). The largest and most elaborate of these structures are located in Chaco Canyon, New Mexico, which was an influential center between about A.D. 900 and 1150.

The Mogollon (pronounced muggy-own) region includes vast expanses of the Chihuahuan desert of New Mexico and northern Mexico, as well as the Mogollon Mountain range across east-central Arizona. People who lived in the Mogollon region in the distant past had much in common with people living in the Ancestral Pueblo region, and were probably also among the ancestors of modern Pueblo people and even other contemporary communities in the southern Southwest and Mexico. Still, we see some interesting differences between these two ancient populations.

The earliest Mogollon villages comprise clusters of small pithouses, typically with ramp entryways (meaning people entered from the ground rather than through the roof). Potters in these communities made brown ware and red ware pottery by coil-and-scrape, and they often elaborated the exteriors of vessels with textural elements, such as scoring or incising. As in the Ancestral Pueblo region to the north, people in the Mogollon region also built structures that archaeologists call great kivas, though the forms were different. Mogollon great kivas are sometimes shaped like a kidney bean, or are rectangular a bit later in time, and they often have ramp entryways, much like typical houses in the region.

After about A.D. 1000, the Ancestral Pueblo and Mogollon regions became more similar. Mogollon populations began to live in aboveground stone-masonry or adobe pueblos, and in some areas, potters began painting black-on-white pottery similar to that made in the north. Opinions differ as to the distinctiveness of the Mogollon and Ancestral Pueblo regions later in time.

The Mogollon region in southwestern New Mexico includes the Mimbres culture area, which archaeologists see as a branch or subgroup of the former. The region is famous for the beautiful and expressive black-on-white pottery artisans produced there, depicting animals, people, and narrative scenes, as well as geometric designs.

The Hohokam (ho-ho-kahm) region falls primarily within central and southern Arizona. People in the Hohokam region were probably among the ancestors of contemporary southern desert populations, such as the O’odham, as well as Pueblo populations and perhaps other populations in northern Mexico. Population declines and other changes occurring late in the precontact period, in the 1400s, suggest that connections between past and present populations are likely quite complex, however. That’s a story Archaeology Southwest and others are still investigating.

Early Hohokam settlements consist of clusters of shallow pithouses, which we sometimes call “houses-in-pits,” because their walls are mostly aboveground. Archaeologists find these dwellings in sets of three or four around small courtyards. Between about A.D. 800 and A.D. 1100 (or even a bit earlier), many villages also had large earthen constructions that archaeologists identify as ballcourts. People probably used these oval depressions for public gatherings and a game played with a ball made from the rubber of the guayule plant, native to the Chihuahuan Desert. The form of the courts suggests that the game was probably similar to one or more of the ball games played among Mesoamerican societies. (You can see reenactments a Maya version of the game here.)

Later in time, after about A.D. 1150 or 1200, people in the Hohokam region started building their houses as aboveground compounds, often containing several adjoined rooms and a walled courtyard. Larger villages then had a different kind of central construction: large platform mounds, often with structures on top, that appear to have been the place for religious and political activities.

Throughout their history, potters in the Hohokam region produced brown and buff ware pottery, sometimes painted with geometric designs or life forms in red—though this tradition may have stopped in some places earlier than in others. They formed vessels by the paddle-and-anvil technique, building up and thinning clay walls with a paddle (held outside) and a stone anvil (held inside).

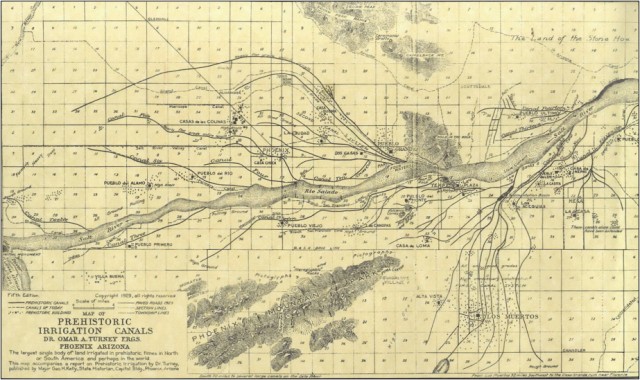

One of the salient features of populations in the Hohokam region is their use of massive-scale irrigation for farming. They built vast canal networks, with some canals more than 20 miles long! There are more than 500 miles of documented canals in the region, representing the largest-scale irrigation in North America. European settlers actually cleared out and reused many Hohokam canals hundreds of years later.

As the map at the beginning of this post shows, there are other archaeological culture areas with long traditions of archaeological research that we haven’t touched on here: Patayan, Sinagua, Trincheras, Casas Grandes. Those areas may be the subjects of future blog posts.

So, what are we trying to learn about ancient residents of the Southwest? On Friday, I’ll offer my answer.

One thought on “Back to Basics, Part 2: Archaeological Cultures in the Southwest”

Comments are closed.

Explore the News

Related to This

-

Location Elden Pueblo

-

Location Tuzigoot National Monument

Matt, I would like to use the image of the Southwest regions in a published version of my paper in the David B. Warren Symposium at the Houston Museum of Fine Arts. To whom should I send a request to? Thank you