- Home

- >

- Preservation Archaeology Blog

- >

- Flight of the Phantom

As I mentioned in my last post, I wanted to wrap up 2013 with a little cautionary tale about the use of unmanned flying cameras, commonly called “drones” in the media. In the Pretty Rock blog post, I illustrated how a revolution in generating three-dimensional data from photography is changing how archaeologists are able to map, measure, and document archaeological sites. Popular websites have been publishing these results for the past few months. Eager to give this new technology a trial, I set out to gain some experience in using a quad-rotor device to be able to loft a small camera and gain aerial perspectives on archaeological features. Eventually, this practice would improve my own efforts to map and model places of the past in modeling software such as Photoscan. Because this was a purely experimental effort, I did not wish to risk Archaeology Southwest’s resources, and so what follows was a project that I conducted with my own funds, and on my own time. First off, for the camera platform, I chose the DJI Phantom. The choice was made based upon the low cost of the device and the fact that it was not actually a “drone.” Rather than flying along a predetermined course defined by GPS checkpoints, I wanted to be able to maneuver the device to exactly where I wanted the camera to point. With a fair bit of experience with remote controlled airplanes and helicopters—and a rather rusty skillset from flying Cessnas for a few years—I was confident in my choice. I was even more reassured by the technical specifications, which demonstrated how the “Phantom” used connections with GPS satellites to maintain stable flight, hover at a fixed location, or even automatically return to the launch site if something went wrong.

I’ll admit to a bit of “go-fever” when Amazon delivered the quad-rotor. I charged up the battery and took my new associate to a local park. As the sun set, The Phantom was behaving perfectly. The blinking light codes flashed green after a brief warm-up period, indicating that the Inertial Measurement Units were ready and that the little copter had successfully connected with at least 7 satellites for a GPS lock. With a flick of the control levers, the phantom popped up into the air, settling on a spot about 3 meters (ten feet) off of the ground, and then it stopped and maintained its position. I was amazed. A breeze from the west did not matter; it was locked in its place in the air. Running out of daylight, I reluctantly landed the device and returned home to attach the camera and try again on the next day.

The issue of the camera turned out to be more complicated than I had anticipated. The first problem was the selection of the camera itself. The Phantom comes equipped with a camera mount for the GoPro wide-angle camera, which I had already decided to avoid. The GoPro is a great choice for artistic aerial photography. It is rugged, fairly shock-proof, and the wide angle makes for dramatic overhead shots; however, the camera uses three “cheats” that distort images in ways that result in poor photogrammetric results. The first cheat is a very inexpensive plastic lens that introduces strong image distortions. The second cheat is something called a rolling shutter, which uses a smaller-than-normal camera sensor to scan across the light coming through the lens, rather than capturing an image frame in one exposure. This results in a “wobbly” or “jello” effect that can distort images in obvious and some not so obvious ways. The final cheat is in the software of the camera itself, where some pretty amazing types of image processing computations are used to try to correct for the problems described above. These issues are problems not just on GoPro cameras, but on pretty much every cellphone camera for sale today. All of these issues add up to a type of camera that might shoot great pictures, but I would not trust these devices for archaeological documentation.

Typical field projects are expensive endeavors. The last thing you want to have happen is to travel to a remote site, collect your images, and then realize that image distortions have already doomed your photomodeling effort after you have returned to your office. Even worse, imagine publishing data that was in error because your camera lens had compressed actual feature widths by 10 to 15%!

Instead of the GoPro, I chose a Panasonic Lumix camera, which featured everything needed for photogrammetry: GPS location data, orientation to magnetic north, and orientation to the plane of the earth’s gravity is automatically encoded on every image. I had managed to get the camera mounted to the quad-rotor’s fuselage before I discovered that the Lumix was not very useful, because the minimum interval for the time-lapse function was 1 minute. The Phantom had about 15 minutes of light time per charged battery, and instead of collecting the hundreds of images per flight that were needed, the Lumix Camera would only collect fifteen exposures.

“Hello, Amazon? I need to speak to your returns department…” So, despite this disappointment, I prepared for my second test flight, this time carrying the weight of a spare digital camera. I set the camera to record video and went into the desert for better real-world shooting conditions. Once again, The Phantom got itself warmed up and flashed the blinking light codes for the GPS lock. A flick of the control levers, and it rose in the air—yet, once the controls were released, rather than hovering in place, the quad-rotor started moving to the starboard (right) side of its airframe. As it started to fly away from me, I brought it back down for a soft if bumpy landing. You can watch this flight in the video segment below.

Clearly, something was wrong, so I went back to the home office and got to work. I updated the Phantom Bios (the quadcopter’s basic programming), recalibrated all of the inertial measurement sensors, double-checked that the radio signals from the remote control were functioning properly, and carefully, manually rebalanced the propeller blades. Bad weather kept me grounded for a few days, but, finally graced with a calm, sunny morning, I went to a local park to see if my adjustments had taken hold. The following cellphone video records the…debacle.

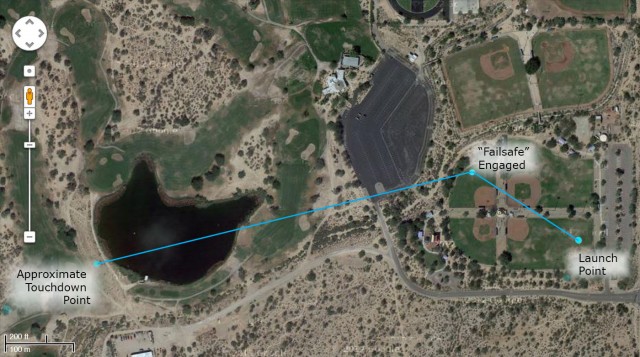

As the video illustrates, at first, it was perfect. “Parked” a meter off the ground and stable. But then it started climbing. No response from the controls. It climbed higher and higher and again started drifting to the right. Then, as it headed for a high school parking lot, I had visions of the Phantom’s rotors getting tangled in some poor kid’s hair, and the inevitable liability lawsuit. So, I activated the GPS fail-safe by turning off the remote unit. But, rather than turning around and returning to its launch point, it rotated 60 degrees and flew away, ascending until out of sight (as seen in the last three seconds of the video). I don’t know if you’ve ever had the chance to watch $1,000 worth of equipment inexplicably and uncontrollably fly away from you, but I can assure you that it is not an enjoyable experience.

I searched for an hour before giving up, returning home, and using Google Earth to plot what I thought would be the most likely impact point. Back at the park, I continued my survey, and was pleasantly surprised to find that rather than crashing, or landing in the golf course water hazard, the little quad-copter was intact, just sitting there with the low-battery indicator blinking. Apparently, it had made a soft landing just off the edge of the pond. “Hello, Amazon? I need to speak to your returns department…” The nice person at the Amazon store said I could get a full refund or exchange for a new system, and indicated that they had received enough complaints about “fly-away” issues that they feared a hardware defect. The ghost in the machine? I opted for the refund.

To be sure, many other people have had much better luck with their DJI Phantom Quadcopters (see Robert Mark’s work with Rupestrian Cyberservices, for example). But, my experiences have convinced me that my desire to manually control the flying camera was in error. My next attempt will utilize an Audrino-based GPS-guided flight-control system with a Canon camera that can be controlled by the CHDK. The CHDK (Canon Hack Development Kit) allows you to program your own interval for time-lapse photography, and I suspect 1 image per 10 seconds of flight should do an adequate job.

Unfortunately, I will not try this again until 2015, when the FAA is expected to clarify the regulations and use of unmanned flying systems for applications such as mapping, research, and photography.

So, for now, we wait on the FAA and utilize trusty technologies, such as kites to take advantage of the revolution in photometric modeling and reality-capture software. And speaking of reality-capture software, I’m pleased to be able to share that Autodesk just donated about $15,000 dollars worth of such software to Archaeology Southwest. We now have access to a whole new set of tools for processing the high-resolution data generated by these new modeling programs. More details to follow in 2014, so stay tuned to Preservation Archaeology, and have a happy New Year!

4 thoughts on “Flight of the Phantom”

Comments are closed.

Explore the News

-

Join Today

Keep up with the latest discoveries in southwestern archaeology. Join today, and receive Archaeology Southwest Magazine, among other member benefits.

Nice try, Doug. Janine Hernbrode (documented Sutherland Wash petroglyphs) said that someone is going to use their drone to photo a geo-glyph. Assuming his is already working satisfactorily, would you like me to get his contact info?

Sorry to learn of your problems. So far, we have not lost our Phantom, but I have heard other stories. See some of our results at http://www.rupestrian.com/quadcopter.html

and http://www.rupestrian.com/PecosConfPhantomPoster.pdf

We have been able to generate PhotoScan 3D models with rectified GoPro images. We are also waiting on the FAA, but hope they will have regulations for the very light models in 2014.

I’m going to echo Bruce, Doug. This was a brave and impressive attempt! I ran into a guy with drones at the Rillito Riverpark who was quite experienced and adept, and very enthusiastic about the use of a quad-rotor for archaeological purposes. He did a very nice video of the Roosevelt Lake area, which I will send to you with his contact info. He might be able to help!

Hey Bruce – Janine is probably referring to Robert Mark, who has posted below your comment.

Many thanks

Doug