- Home

- >

- Preservation Archaeology Blog

- >

- Food and Fertility

I was on Scott Michlin’s radio show for my monthly visit in July. You can listen to our conversation here.

The topic was a recent study that discussed an ancient baby boom among the Pueblo people of the Southwest. Tim Kohler and his associates recently published a paper that summarized several hundred years of demographic (population) changes in the northern Southwest.

I’ve been interested in ancient Pueblo population since I completed my master’s thesis in the late 1980s, which examined fifteenth- through seventeenth-century Eastern Pueblos in the area surrounding Santa Fe. I’ve also been interested in population at a much earlier point in time, during the long Basketmaker era. My colleague and friend Peter Kakos completed some interesting research a few years ago that bears directly on the ancient population boom. I asked Peter to share his work in this blog post.

Here’s Peter:

My research into high glycemic index (high sugar carbohydrates) foods led me to observe that body fat may have been a more important factor in determining actual fertility than I had previously thought. Now, I believe that storage of body fat appears to be the single most critical factor for understanding population growth itself. In fact, a 30-year Harvard study by Rose Frisch conducted on thousands of women seems to confirm that a critical fat-store to body-mass ratio must be reached even before first menarche occurs in adolescent females. Furthermore, it is now apparent from these studies that a woman must maintain body fat or critical fat stores to ensure continued menses and thus fertility.

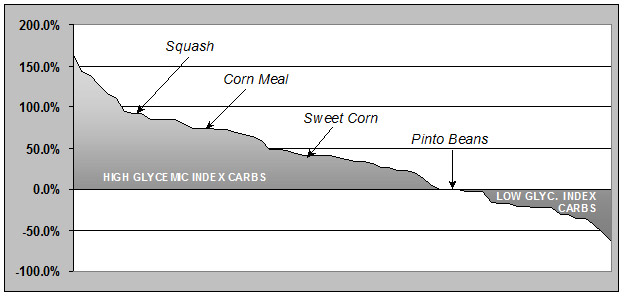

During most of what we know as the Archaic time period, foods available to hunter-gatherers may have fallen well below the G.I. value for pinto beans. Why? Because most of those foods were fibrous, and are considered diluted sources of carbohydrates, and thus have low corresponding glycemic index values. So low, in fact, that body fat may have been hard to maintain (unless excessive amounts of calories were consumed, an assumption not really justified) because there were no effective sources of high-glycemic foods available. This contrasts sharply with cultivated foods such as corn, beans, and squash (the three sisters). The Basketmaker food package included higher glycemic foods compared to the lower glycemic foods available for most hunter-gatherer populations.

What we call Formative cultures, such as the ancient Pueblo people, were involved with incipient agriculture and exhibited a population growth rate of about 0.1 percent. This is about 100 times that given for most hunter-gatherers around the world. Why population growth should have changed so drastically in so short a time has been the subject of much long and labored debate (which I will not repeat here—you’re welcome).

It is proposed that the cultivation and consumption of high glycemic index foods is a causative factor in the rapid climb in population rates. It has been suggested that high-glycemic carbohydrates stimulate the production of the hormone insulin, which in turn signals the body to store fat and keeps the body from using its own stores of fat. This is a crucial point in understanding potential fertility patterns, and ultimately population growth, in the past and present. If reproductive spans lengthened as a result of a decrease in the age at menarche, shortening of adolescent sterility, and lowering in the age at nubility, then the overall growth rate would be proportionately much greater.

For people of the Basketmaker era, then, living entailed adaptive strategies focused primarily on maize agriculture. From a nutritional standpoint, the primary effect that maize agriculture had on ancient Southwest populations was the ability to store large amounts of calories (whether in corn, beans, or squash), especially high glycemic index carbohydrates, which promoted population growth.

Research has shown that an increase in the percentage of body fat in women directly affects fertility rates by lowering the age when first menarche occurs, reducing the time of adolescent sterility, lowering the age of nubility, and decreasing the interval between child births. These factors positively affect fertility rates and ultimately population growth. Absent any evidence that cultural population control methods changed during Basketmaker II and III (and no one has suggested this happened), and absent the introduction of new diseases or a change in mortality rates (again no studies suggest this occurred), local populations could conceivably have doubled every 20 or 30 years. Because of the increase in fertility rates, it comes as no surprise that demographic models presented for the prehistoric Southwest (and elsewhere) indicate positive population growth throughout most time periods until final residential abandonment of the northern periphery of the Colorado Plateau.

Missing from previous demographic studies was a causal mechanism—a proximate cause—which could have triggered a change in intrinsic population growth in the first place. In most demographic studies population growth is merely assumed to be inherent in human populations, as with Malthus’s original study. Such studies also assume that the storage of more calories naturally increased the carrying capacity for local populations, which promoted population growth and density for these early time periods—and this probably occurred at various times and places. But it is clear that the persistent increase in population growth through time more than likely reflects increases in intrinsic fertility rates initiated first by the adoption of and then the reliance on maize agriculture, which further influenced the overall fecundity of those people.

This fecundity was not due merely to the amount of calories being stored and eaten, but also to the kinds of calories being stored and eaten. As the research presented here indicates, high glycemic index foods influence the production of insulin, which in turn not only signals the body to store fat but also inhibits the body’s ability to use stored fat. This positive feedback loop in the nutritional cycle kept the Basketmaker population in a kind of fertility zone that had consequences which sustained these populations throughout the prehistoric time period.

In separate areas of the New World—and in the Old World—where high glycemic index foods were first being produced and stored, population growth seemed to have followed at an accelerated pace. This was especially true in the Valley of Mexico, the Mayan Lowlands, in Peru, and in the Southwest. Without these high-yield grains and other high-glycemic foods, the great civilizations of the past may never have come about, nor could large numbers of people have been sustained, because the food packages utilized within hunter-gatherer systems promoted low insulin responses, which in turn affected low body fat and apparently low intrinsic fertility rates. Reliance on grain-based agriculture, however, gave rise to and sustained larger populations.

To learn more:

Kakos, Peter J.

2003 Living in the Zone: Basketmaker Food Packages, Hormonal Responses, and the Effects on Population Growth. In Anasazi Archaeology at the Millennium: Proceedings of the Sixth Occasional Anasazi Symposium, edited by P. F. Reed, pp. 35–56. Center for Desert Archaeology, Tucson.

Explore the News

-

Join Today

Keep up with the latest discoveries in southwestern archaeology. Join today, and receive Archaeology Southwest Magazine, among other member benefits.