- Home

- >

- Preservation Archaeology Blog

- >

- George McJunkin and the Discovery That Changed Ame...

On August 27, 1908, the small town of Folsom (population ~250) in northern New Mexico was hit by a cloudburst and drenched with a rapid and heavy rain. This storm caused some of the worst flooding ever recorded in the area. First-hand accounts in newspapers describe a harrowing night: water violently rushed through the streets, flooding homes and businesses as people clung to furniture and climbed to their roofs to stay safe. At least 17 people died. Water still flowed through the streets the next morning.

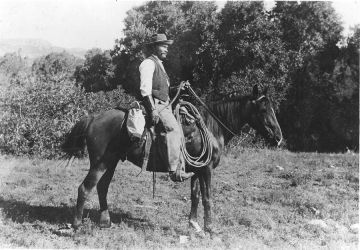

One resident of the Folsom area on that night was African American cowboy George McJunkin. McJunkin’s life story is remarkable. He was born a slave near Midway, Texas—a small village about halfway between Houston and Dallas—in 1851. George’s father was a blacksmith, and George grew up around horses. Eventually, he learned to ride and rope.

Soon after the Civil War, and as a free man, George left Texas for northern New Mexico to seek work as a cowboy. He did, and he excelled, gaining a reputation as one of the best horse breakers in New Mexico. Those who knew him described him as a curious person interested in learning, particularly about science. He learned to read from other cowboys in his spare time on the range, sometimes trading horse-breaking lessons for reading lessons. He also knew Spanish, and became somewhat of an intermediary between the Mexican and Anglo communities in the area. He even fiddled quite well! Sometime in the early 1900s, he became the foreman of the Crowfoot Ranch near Folsom.

On the day after the Folsom flood, McJunkin was out checking fences and arroyos for damage. Along one of the side drainages of the Dry Cimarron River (not so aptly named for the summer of 1908), he and friend Bill Gordon saw a newly incised cut along an area they called Wild Horse Arroyo. It was in this arroyo that McJunkin would make one of the most important discoveries in American archaeology. Approaching the arroyo, he saw bones he recognized as bison, but they were much bigger than any bison he’d seen before.

George knew this discovery could be significant, and he spent the rest of his life trying to get others interested. He wrote to an expert in Las Vegas, New Mexico, who had studied mammoth bones and remains of other animals. Bill Gordon and George also showed some of the bones to people in Raton who had expressed interest in finding evidence of extinct animals.

George McJunkin died in January 1922, never able to solve the mystery of the giant bones. Just a short seven months after his death, however, Carl Schwacheim (one of the people in Raton whom George had told of his discovery), a banker named Fred Howarth, and a group including a Roman Catholic priest and a taxidermist finally did pay a visit to the now-famous Wild Horse Arroyo. Schwacheim, Howarth, and company wrote notes of their visit to the site remarking on the huge bones and stone spear points they found eroding out of the arroyo.

A few years later, in 1926, one of the members of that team approached J. D. Figgins of the Colorado Museum of Natural History—now the Denver Museum of Nature and Science—with some of the bones from the Folsom site. Figgins hadn’t seen bones like those before and thought the site could be important. He and Harold Cook, also of the Colorado Museum, began formal excavations at what they now called the Folsom site in 1926. Their work revealed numerous bones from at least 30 extinct bison, today known as Bison antiquus, which hadn’t yet been described in the scientific literature.

In the summer of 1927, they made an even more exciting discovery: they found a stone spear point in situ in the soil in between the ribs of this extinct species of bison. (Link opens as a PDF; scroll to page 9.) At the time, most archaeologists and paleontologists believed that people had only lived on the North American continent for about 4,000 years. Figgins and company had direct evidence of people (the spear point) in association with an animal that had gone extinct many thousands of years earlier. This discovery meant that people were living in the Southwest more than 11,000 years ago (and new discoveries in the years since have pushed that date even further into the past). The Folsom site was the first site generally recognized as evidence of the great antiquity of human habitation in North America, and it set off a huge wave of interest in archaeology in the Southwest and the Pleistocene period in general.

This significant discovery would not have happened as it did without George McJunkin. McJunkin found the site, knew it was important, and persisted in bringing it to the attention of the scientific community, even though he didn’t live to see the result. McJunkin’s contribution wasn’t widely recognized, however, until almost 50 years after his death, when George Agogino of Eastern New Mexico University heard stories about McJunkin from people living in the Folsom area. Agogino and writer Franklin Folsom tracked down and recorded stories from those who knew George McJunkin, thus documenting his role in this discovery, as well as his remarkable life.

More on McJunkin:

Folsom, Franklin (1992) Black Cowboy: The Life and Legend of George McJunkin. Roberts Rinehart Publishers, Niwot, Colorado.

What should I do if I discover a site?

It is likely that archaeologists have already documented the place and there is an official record of it. This is especially true of sites on public lands. Still, contacting a visitors’ center (for public lands) or a local college, historical society, archaeological society, or museum is worthwhile, just to learn more about the place and the people who may have been there. Many states have a state museum that would be a good place to start. You can also contact us at info@archaeologysouthwest.org to help direct your inquiry.

Please do not remove artifacts from the site. When objects are moved from where they were found without proper documentation of the location and surrounding context, important information is often lost. Certain questions artifacts can address require this information. Moreover, it is illegal to remove artifacts from public lands, such as national parks, monuments, and forests, as well as from state or municipal lands, without the proper permits. Take photos instead.

If you suspect or know that a site is present on property you own, you are under no obligation to contact archaeologists, but at minimum, we ask that you enjoy, preserve, and protect what is there in place. If you’d like us to help you identify the artifacts, document the site, or advise you on how to protect the remains, please contact us at info@archaeologysouthwest.org. Many times, it is helpful just to learn that a site with certain cultural traditions is present in a place.

5 thoughts on “George McJunkin and the Discovery That Changed American Archaeology”

Comments are closed.

Nice article. Thanks!

Loved the article. Always been obsessed with the Folsum Point and the importance of its discovery. Thanks

Very interesting to read Tony Hillerman’s description of Mr. McJunkin and the unfolding of these events in his short story, ‘Othello in Union County’. Published in 1973.

I learn something new every day and this is a exciting read. Thank You

As a Chicago high schooler, I occasionally found small marine fossils in railroad track ballast near our house. In Altoona PA, I found a trilobite fossil, about 1 1/4 inches long, on the floor of deep, dark wooded area near a later home. Don’t look askance at seemingly ho-hum rock piles, such as gravel parkway ground covers. You never know what OLD wonder may be offering itself!