- Home

- >

- Preservation Archaeology Blog

- >

- Gopher Jaws and the Past

(October 2, 2015)—I spent this week in beautiful southwestern Colorado working on the first phase of a new research project using animal bone chemistry to examine how people’s access to food animals changed over time in the Mesa Verde area. I wrote about this project on our blog a few months ago, and am looking forward to delivering our first batch of samples to archaeological chemistry expert Jeff Ferguson when he visits for our Archaeology Café on Tuesday night.

Most of the collections Jeff and I are using for this project are curated at the Anasazi Heritage Center, a museum and repository that houses over 3 million artifacts and records from archaeological projects in southwest Colorado. I’m particularly excited to work here because this museum was also the site of my first job in southwestern archaeology, as a curation intern in 1996. The amazing field trips the museum staff organized for my cohort of interns are part of what drew me to specializing in Southwestern archaeology as an undergraduate.

The first phase of this project has consisted of looking through hundreds of curated bags of animal bone in search of gopher jaws. Gopher bones are pretty common in archaeological sites in this area, and these little animals are unlikely to move long distances or to be carried between villages by humans. These characteristics mean their bones reflect the chemical signatures of the geology in the specific area where the animals lived. Jeff and I are sampling gopher jaws from many different archaeological sites to identify the isotopic signatures of geologically distinct parts of the study area. Once we have this baseline information, we’ll return to sample larger species (like deer and turkeys) and match up their isotopic signatures to these different geologic areas to determine where ancient people successfully hunted game animals, and how that changed over time as human populations grew and some species became harder to find near villages.

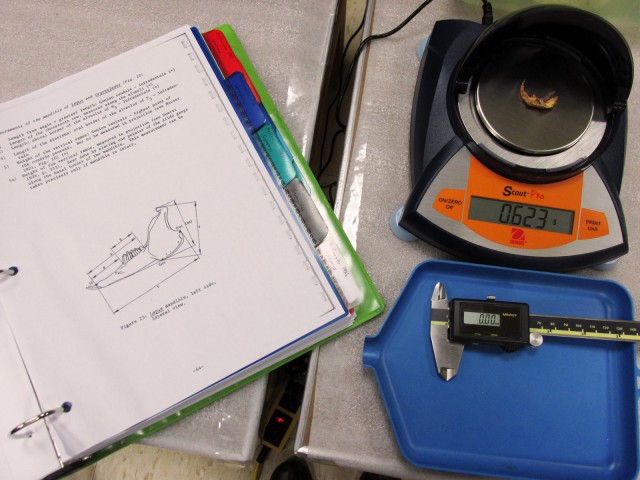

Isotope analysis involves removing a small piece of each bone, so we had to go through several stages of approval to get permission to do this study. In order to retain as much information as possible about each bone for future researchers, I photograph each specimen and take 15 to 20 different measurements of the bone and teeth. Then I cut off a sample and return the rest of the specimen to the collection. It’s a time-consuming process, but luckily for me, the museum curators know exactly which room, shelf, box, and bag to go to in order to find each one of the millions of artifacts in their collections. All these photos and measurements (and eventually the isotope data) will also become part of the museum collection, so we’ve just added yet another batch of records for them to keep track of!

This project has involved examining bones from some legendary archaeological projects, such as the Dolores Archaeological Project from the 1970s and early 1980s and the many projects run by Crow Canyon Archaeological Center. I’ve also been introduced to new projects and sites, like the interesting work at Mitchell Springs by Four Corners Research. I’m looking forward to the results of our gopher bone analyses, and to applying what we learn from this phase of the project to our larger research questions about hunting and game animal species in the past.

Thanks again to the National Science Foundation (BCS-1460385) for their support, and to Crow Canyon Archaeological Center, Four Corners Research, and the very patient curators at the Anasazi Heritage Center for their help with this project. May all your lawns be gopher-free!

One thought on “Gopher Jaws and the Past”

Comments are closed.

Very informative update!