- Home

- >

- Preservation Archaeology Blog

- >

- My Flintknapping Problem

(December 17, 2015)—I was reading an old book (1927) about artifact collecting recently, and I came across a funny line. The author, Virgil Y. Russell, offered this advice on how to make “Indian arrowheads”:

Don’t. Never even try. It is just as foolish as it would be to counterfeit money, but if it became known that you were making it, it would surely cause a great deal of trouble.

That perspective has not changed much. Artifact collectors have long been tormented by artifact forgers. The prices the former pay for some projectile point styles are extreme, making it an easy way for an unscrupulous person to make quick money.

Now, I am obviously not defending forgers or collectors. The latter have destroyed much important archaeological information in their relentless quests to own artifacts. And forgers are forgers. But I do want to write about flintknapping as a legitimate craft and art form—possibly verging on an addiction.

(People who make stone tools by striking or flaking are today called flintknappers. This term derives from the manufacture of gun flints in Europe in the 1800s.)

Previously, I have written about how flintknapping contributes to our understanding of the archaeological record. Learning to replicate ancient toolmakers’ techniques helps us understand what we see in archaeological sites. Studying flakes and debris as well as the finished products enables us to ascertain why they did things the way they did them. Even more than that, though, it is impossible to do without gaining great respect for the stone tool makers of the past.

Flintknapping has become quite popular, and it is practiced by fascinated archaeologists and hobbyists alike. There are thousands of how-to videos online, making it much easier for beginners to learn. When I started flintknapping—uh, let’s just say, before the Internet—I was still in high school and working summers at Crow Canyon Archaeological Center. There were a few how-to books out there, but knowing somebody who could teach you was the best way to learn, and I was lucky to have that in Bruce Bradley. In the beginning, I was knapping at least 3 to 4 hours a day.

Finding high-quality rock for making points became an obsession, too. Over the years, I have hauled in a massive quantity of rock! There are some ethics to harvesting good flaking rock so that the archaeological record isn’t damaged or contaminated—we don’t want to create new sites. Moreover, flintknapping should never be done on or near sites. Most places with high-quality flaking stone today were also used in the past, and are covered with artifacts from the quarrying process. Collecting material people used and discarded in the past, or striking flakes into such materials, destroys the archaeological record. So, I collect in rivers and washes that have exposed new, unworked material. I test cobbles in washes or rivers that have no context, as everything is washed away when it floods.

For me, the most enjoyable aspect of flintknapping is the process of making a biface. This is done to thin a piece of stone down to become a dart point, arrowhead, or knife. This process is done by striking flakes back and forth across a piece of stone. Each flake is created by a wave of energy that travels through the stone when it is struck along a margin (prepared edge). These days, I enjoy that process more than the finishing of a point. An unfinished biface has lots of potential in it, and can become anything I want it to be. Finishing it limits what it can be.

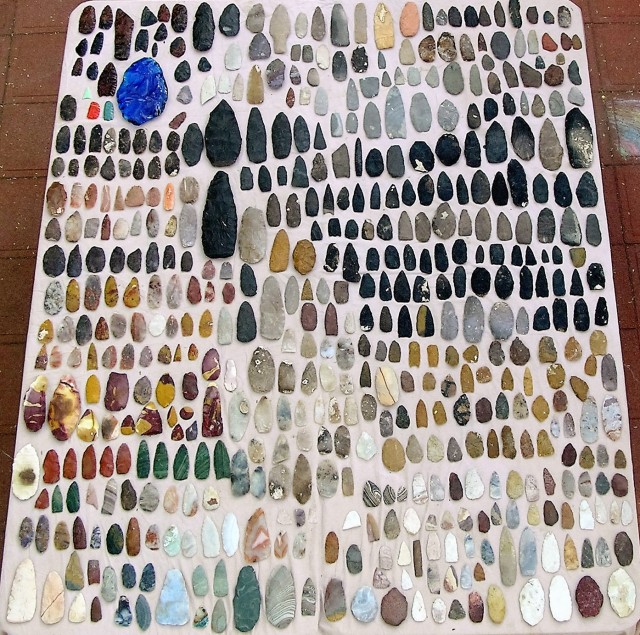

Needless to say, the bifaces have started piling up. I decided to pull a bunch of them out the other day and take some photos to show the scale of my problem. Most of them are middle- to late-stage, with a few early-stage bifaces, as well. I suspect it would take hundreds of hours to finish the bifaces in these images. I have stone from at least eight states and four other countries on that table!

|

|

It takes a lot of practice, but it’s an obsession satisfying hobby. I have put more hours into it than I could ever calculate, and still I can’t get enough.

If you are interested in learning how to knap, I teach classes here at Archaeology Southwest—including one this Saturday, December 19, 2015. In these classes we reduce a chunk of obsidian into a pile of flakes, then attempt to make a projectile point out of one of these flakes. If you can join us sometime, you might come away with your own wonderful new addiction to breaking up rocks!

2 thoughts on “My Flintknapping Problem”

Comments are closed.

I am jealous!!!!!

first time flintknapping is a kick. I am with you that it cound be addictive. Thanks for the experience. Hopefully we can cross paths a few times this winter and I can continue to learn from you.