- Home

- >

- Preservation Archaeology Blog

- >

- 50-Dollar Words, 1-Dollar Ideas, and Priceless Peo...

(August 30, 2016)—Archaeologists are really good at making up words, or at least turning nouns into verbs in really awkward ways. Many site reports in the English-speaking world are littered with the word “recordation,” as in, “this site underwent recordation” instead of “we recorded the site.”

Part of this has to do with a trend in archaeology since the 1960s to make our discipline more science-y. This led to a massive increase in the passive voice in archaeology (and other social sciences). People stopped recording hearths. Instead, hearths were recorded.

Somehow.

Magically.

Hearths were recorded. Anthropology itself, and really most of the social sciences, is also pretty good at using $50 words (“neologism”) for $1 concepts (“new word”). One of these $50 words is phenomenology.

Phenomenology essentially means that we can understand other cultures—and for archaeology that we can understand the past—through experiential means. People are people: if we situate ourselves within our shared human perspective, then we should be able to understand other groups or people in different times. (It’s a bit more complicated than that, of course— and also includes rejections of earlier philosophical principles, efforts to engage with an experience as it occurs and avoid any preconceptions and misconceptions based on cultural traditions, and a wide variety of types of phenomenology. There are some interesting overlaps and conflicts with ontology and epistemology, as well).

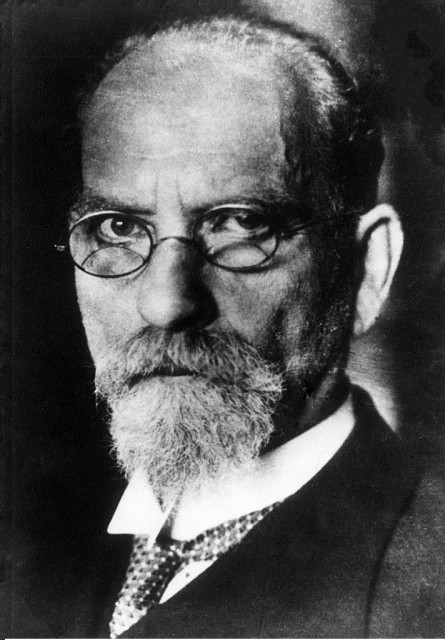

The idea, though, is that it is possible to experience the same thing that someone else experiences. This is pretty controversial, and many anthropologists have spent their careers dealing with the conflict inherent in using phenomenology within a discipline that argues there are differences between groups of people that are embedded through enculturation that necessarily color all experience. Edmund Husserl, one of the early philosophers who helped develop this idea, argued that there was a way to step outside of that experience, though. He even detailed the steps necessary to do this.

Although this might sound undoable, in many ways, this is exactly what the scientific method attempts to do, as well—because our biases are tough to perceive and yet they permeate almost everything we do. At minimum, phenomenology is a useful concept, because it essentially allows us to sit down and understand each other. Otherwise, the cultural mélange is pure Babel, and we really have no basis for arguing that we can talk about anyone besides ourselves (and psychology says that we can’t talk about ourselves, either).

In archaeology, we have some mixed thoughts on phenomenology. Some people find it incredibly useful at adding humanity back into research on the past. Others think that it is a flaky, unscientific, and unsupportable attempt to understand the past. As with most things involving humans, the reality is that it is many of these things all at once (“intersectional” is the $50 word). Phenomenology can be a supportable way to study the past, as well as add humanity back into research on the past.

My colleague Allen is particularly good at this type of experiential work. His explorations of the past involve examining traditional technologies (and he’s also an amazing field archaeologist). Recently, much of his work has been focused on creating ($50 word is “engender”) a sense of wonder about the past by showing people today how past people did things—how they built dwellings, how they made tools, how they used tools, how they processed food—and guiding them to try their hands at it, too.

This is one thing he does. Another is recreating past technologies. That is the more phenomenological side of Allen’s work. In the language of phenomenology, what Allen is doing might be called embodied phenomenology or embodied cognition, something described by Maurice Merleau-Ponty. Merleau-Ponty might argue that Allen is making a connection to past decisions through the physical activity of replicating those actions. In other words, within phenomenology, Allen becomes a bridge from the present to the past. This puts Allen in a unique position to use experiential research, to create ideas that can be tested against the archaeological record. To me this is pretty incredible, because on some level, it also places phenomenology within the scientific method.

In the natural and physical sciences, people often talk about the scientific method as deductive reasoning (as falsifiable hypothesis testing). But that is only a portion of science. The other half, the equally important half, is the inductive part. In the scientific method, this is often the portion where ideas are created; ideas that can then be tested by the deductive process. Allen uses experiential learning to create ideas that can be tested. This makes him an integral part of the research portions of our projects at Archaeology Southwest, because he is often helping to inject different ideas into our understanding of how and why artifacts and architecture were being used in the past.

Now, in all honesty, this also puts me and Allen at odds, sometimes. Not badly, of course. In our discipline, disagreements are par for the course and are necessary to get to the truth, or at least as close to the truth as we can get. It’s just a part of being colleagues and friends in our field. But these disagreements—though often frustrating to everyone involved, because everybody wants someone to agree with their ideas—also means that more ideas about what may have happened in the past can be leveraged to interpret that past. Allen’s experiential perspective from decades of reproducing ancient technology (as well as his vast fieldwork experience) means that he has very valuable insights on how things might have been used or built or broken. How things might have fallen apart (“taphonomy” is the $50 word). These insights can then be added to other ideas on how items were used. And then they can all be tested.

Long story short is that I’m always excited to work with Allen, either making an atlatl with him or talking about dirt, features, and artifacts as we are digging together at an archaeological settlement. And this season once again confirmed ($50 word is “reified”) that Allen is an irreplaceable member of our Preservation Archaeology field projects. Not just in the hands-on portion he runs, but also in excavations at the site, in the lab, and in looking at survey data.

Explore the News

-

Join Today

Keep up with the latest discoveries in southwestern archaeology. Join today, and receive Archaeology Southwest Magazine, among other member benefits.