- Home

- >

- Preservation Archaeology Blog

- >

- Delegating

(October 12, 2016)—What does the day-to-day life of an archaeologist look like? I can’t speak for all archaeologists everywhere because there are many of us working on very different projects, in diverse capacities, and in quite disparate regions of the world. As a Southwest archaeologist, my tasks are fairly narrow in regional scope. But as a Preservation Archaeologist, my day-to-days are often split among a miscellany of tasks. One of my colleagues described her days as a juggling act, and that’s true for me as well. But it is more than juggling…it takes a concerted effort at delegating time and effort as we work toward the mission of Preservation Archaeology.

Lately, I’ve been delegating myself amid a series of projects, all of which have deadlines looming over my head. On my desk right now are an article and book manuscript I’ve agreed to peer-review, as well as a crude draft of an abstract for a paper I’ll be giving at the next meeting of the Society for Applied Anthropology (2017, Santa Fe).

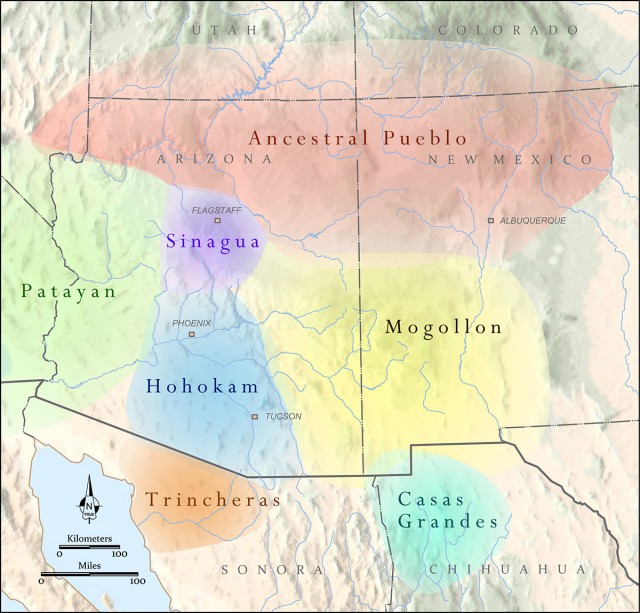

I’m also in the midst of applying for a series of grants to continue our research along the lower Gila River. These efforts are designed to expand our knowledge of the Patayan tradition, at least how it was expressed in southwest Arizona. Patayan is the least understood late prehispanic cultural tradition in the U.S. Southwest. Some may even claim that Patayan isn’t even a Southwestern archaeological tradition: don’t believe them! Granted, Patayan isn’t covered in our college courses on Southwest archaeology, but this is because little research has even been done on this aspect of the past.

Along the lower Gila, Patayan is expressed in fabulous geoglyphs and extremely dense galleries of rock art adorning black volcanic cliffs and weathered granitic boulders. It is also found among the dozens of villages sites strategically placed to harness floodwater from the lower Gila in order to irrigate crops of corn, melons, gourds, and cotton. Yes, I’m talking about sedentary agricultural villages. Are we to believe that the rock art and geoglyphs were crafted by phantoms? The lower Gila contains some of the best-preserved, and most of the only extant Patayan villages. This is because damming and extensive agriculture have obliterated much of the Patayan signature from the valleys of the lower Colorado River, the epicenter of the Patayan World.

I’m also gearing up for a field project to document the Painted Rock Petroglyph Site and conduct a condition assessment of site’s rock art. Last week, Andy Laurenzi and I used our UAV to take over 1,100 aerial photos of this site. Doug Gann is using these to create a 3D model of the site, for curation and digital exhibition. I’ll be spending the first part of winter out there surveying the site area and inventorying the petroglyphs. Painted Rocks is often described as the westernmost Hohokam petroglyph site. That’s strange, because the vast majority of the pottery found around the petroglyphs bear hallmarks of Patayan ceramic technology, the surrounding habitation areas have all been documented as Patayan dune sites, early Spanish journals reference cross-bearers (i.e., Yavapai) as crafters of some of the glyphs, and contemporary Yavapai people refer to the site as a place of prayer and veneration. Need I say more about the complexity of the lower Gila’s cultural landscape, and how rock art crosses cultural boundaries and bridges contemporary social identities with ancestral places?

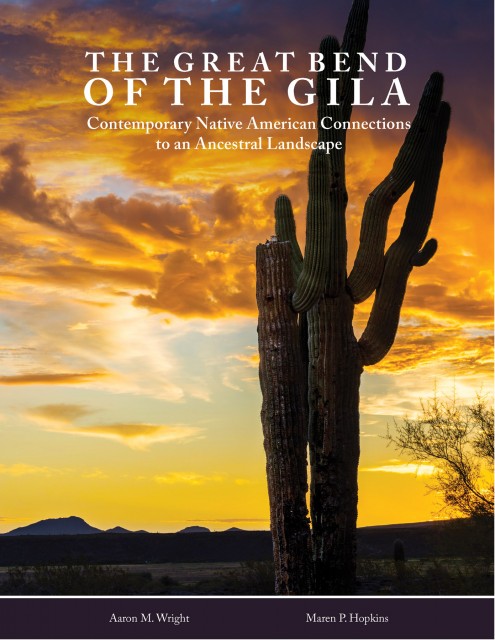

Of course, we must balance work with play, and appreciate our achievements as they arise. Archaeology Southwest recently released a cultural association study of the lower Gila River (opens as a PDF download). As the lead author, I’m very pleased to see this project to completion, and I’ve been reflecting on the results. The final report synthesizes a year’s worth of research and tribal engagement to better learn how contemporary Native American tribes identify with the cultural resources of the lower Gila River.

In the course of our work to establish a Great Bend of the Gila National Monument, it became glaringly apparent that there is an utter dearth of ethnographic information pertaining to the lower Gila River. This was quite surprising, because the people who crafted the tens of thousands of petroglyphs, arranged the desert pavements into mystifying geoglyphs, and resided among the dozens of ancient villages throughout this region didn’t just disappear. Though it’s easy to conceptualize the past in terms of “collapse” and “abandonment,” those are academic cop-outs. Southwest archaeologists struggle to bridge the prehispanic past with the vibrant communities who welcomed Spanish, Mexican, and finally American visitors to their ancestral territories. Our inability to make the link, and our unwillingness to take seriously the oral histories provided by descendant communities is no light matter. As the lingering effects of the Indian Claims Commission and ongoing lawsuits over water rights attest, the ways archaeologist do their work—and the ways they interpret the past—have real impacts on peoples’ lives.

Making the connection between the past and present is what I love about Preservation Archaeology. Sure, I wish I could spend more hours in the field, and I reminisce fondly about the many, many artifacts I’ve found and sites I’ve recorded. But the reason I pursued advanced studies in archaeology, and why I’m proud to be a Preservation Archaeologist, is the opportunity to make the past relevant to the today and the future. For me, archaeology is more than the thrill of discovery and the intrigue of the unknowable. It’s about sharing these experiences and my passion with a broader community—a community that includes the people whose very ancestors crafted the objects and artworks that I admire.

Explore the News

Related to This

-

Location Painted Rock Petroglyph Site