- Home

- >

- Preservation Archaeology Blog

- >

- Salad Spinners, Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Sp...

(October 28, 2016)—October introduced me to an unexpected new archaeological research tool: the salad spinner.

I’ve just returned from a very busy two weeks in southwest Colorado, where archaeological chemistry expert Jeff Ferguson and I completed the second phase of field and museum work for our project using animal bone chemistry to examine how people’s access to food animals changed over time in the Mesa Verde area.

Last year, I spent a week at the Anasazi Heritage Center sampling gopher jaws from twenty different archaeological sites in the region. In the year since, a team of experts (including Jeff, Virginie Renson, and Amanda Werlein at the MURR Archaeometry Laboratory and Joan Coltrain at the University of Utah) analyzed those tiny bone samples using inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry and carbonate analysis to successfully identify the isotopic signatures of geologically distinct parts of the study area. These chemical signatures will now allow us to link the bones of larger animals in archaeological sites to the parts of the landscape they came from, providing insights into questions like how far people traveled to hunt certain species and how that changed over time as human populations grew.

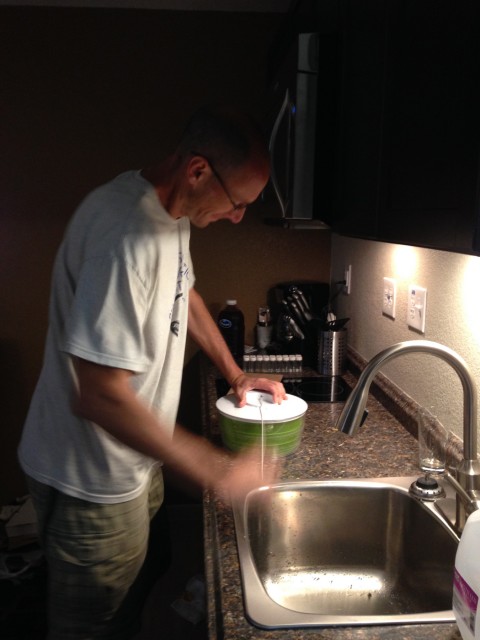

One of our goals this year was to collect plant specimens from those same geologic zones, providing a second line of evidence to chemically characterize each area. Jeff spent his days navigating rough roads in remote locations to snip twigs from sagebrush, oaks, and conifers growing in the many geologically distinct patches of this varied landscape. In the evenings, he put his hotel room kitchenette to good use rinsing the samples in distilled water, drying them in a salad spinner, and desiccating them in a food dehydrator (tucked into his bathroom in a futile attempt to contain the powerful odors of sage and pine that soon permeated everything he owned). I was able to join him on a few of those collection days, when we spent many miles trading stories about our families back home while narrowly avoiding becoming impaled on fallen tree trunks or destroying truck tires on precipitous mountain jeep trails that had always looked fine on the map.

|

|

|

|

|

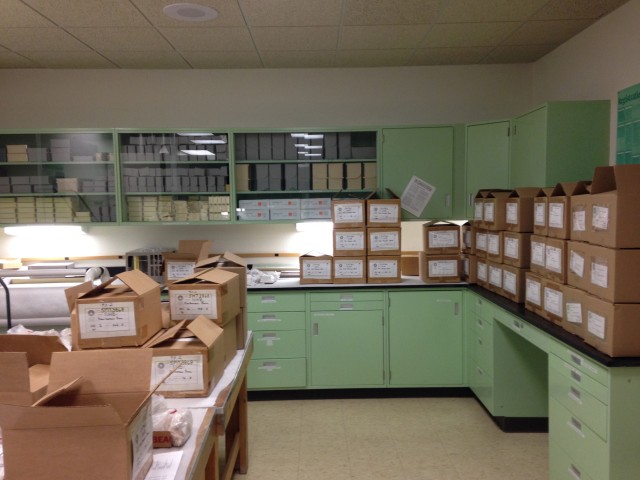

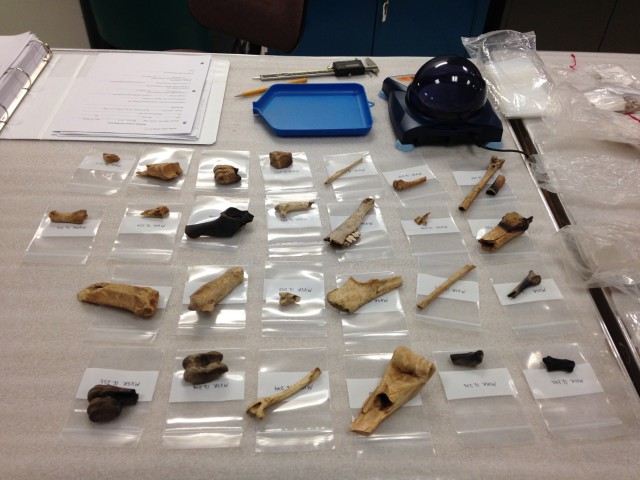

The rest of the time I was back in the now-familiar curation area at the Anasazi Heritage Center, sorting through the rows and rows of boxes curators and volunteers had brought out from storage for me in order to select deer, turkey, and jackrabbit bones from a series of well-dated animal bone assemblages spanning the period from A.D. 725 to 1280. Luckily for me, finding the specimens in the meticulously organized museum collections was pretty straightforward, so much of my time there was spent on measurements, photographs, and other documentation of each bone before removing a tiny chip for chemical analysis.

|

|

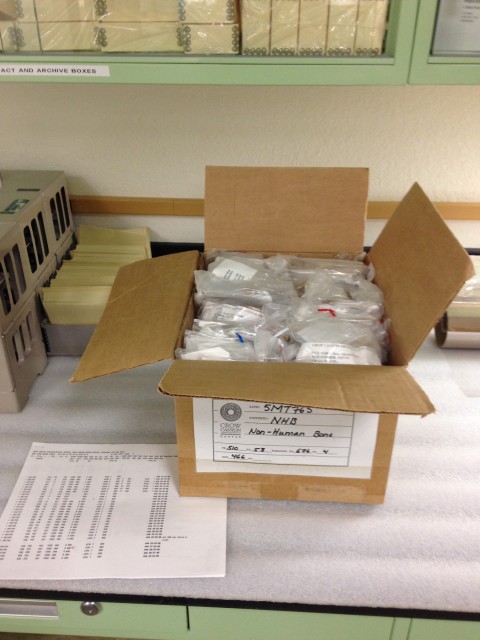

I pulled samples from hundreds of boxes just like this one, each with three layers of numbered bags arranged in numeric order. The hosts of home organizing television shows have nothing on museum curators!

I enjoyed working on three different types of animals this year, and managed to avoid a rerun of last year’s nightly dreams about gophers. I also have a renewed appreciation for the museum’s welcoming space devoted to visiting researchers and for the extent of their collections, which allowed me to complete nearly all of the work required for this large project at a single museum, rather than traveling to multiple research sites. Small notes and labels added to some of the bags by previous projects—like Camilla Speller and colleagues’ turkey DNA work in 2006–2009—were a pleasant reminder of some of the many archaeologists who have used these collections before me and the importance of curating archaeological collections and ensuring their continued availability to generations of researchers.

With two weeks to spend in the area this year instead of just one, Jeff and I were able to fit in brief visits with our friends at Crow Canyon Archaeological Center on their beautiful campus and Four Corners Research at the Mitchell Springs site. We also managed to take one of the last tours of the season at Long House in Mesa Verde National Park, a place I can never visit often enough. As I organize the hundreds of bone specimen records from this trip, I am happily looking forward to the results of the second round of chemical analyses and to adding a small contribution by salad spinners to our understanding of the past in this beautiful and interesting region.

Thank you to Bridget Ambler, Tracy Murphy, and the enthusiastic volunteers at the Anasazi Heritage Center, and to the National Science Foundation (BCS-1460385) for supporting this project. If you are lucky enough to visit the museum and would like to see some of their extensive research collections, public tours are available; please see their website for information.

Explore the News

-

Join Today

Keep up with the latest discoveries in southwestern archaeology. Join today, and receive Archaeology Southwest Magazine, among other member benefits.