- Home

- >

- Preservation Archaeology Blog

- >

- Disappointing Discoveries

(December 16, 2016)—Some of the most exciting dimensions of archaeological work are the instances of discovery—identifying new sites on survey; unearthing features at the bottom of an excavation unit; finding interesting artifacts in the screen; peering at microfossils, use-wear on artifacts, and pottery temper under a microscope; gaining new insights from quantitative analyses; and learning different perspectives on the past through reading or discussion. At its foundation, and at its core, archaeological practice is an exploratory endeavor, and it is archaeology’s sense of discovery that catches the attention of people of all ages, creeds, backgrounds, and walks of life.

There is, however, an antithesis to such excitement. Irreparable damage and total loss of archaeological things and places is utterly heartbreaking. Take, for example, the wholesale pilfering of mortuary vessels from Mimbres villages, where the grim reaper comes in the form of a backhoe. As archaeologists, we encounter sites in all states of preservation. It’s not uncommon to find a village site with looter holes, or even a geoglyph that’s been driven over by off-road vehicles. It can be troubling to “discover” such loss, which leaves you wondering what has been taken from us, what is gone that we’ll never know about or get to appreciate.

For me, the only thing more gut-wrenching than discovering loss and damage, is witnessing and experiencing it. In the nature of archaeological practice, we often don’t revisit the places we’ve discovered. Sites are either recorded and avoided, or they are excavated. After that, we typically move on to find new sites…always thirsting for that next instance of discovery. In this process, we often aren’t witness to what happens to sites after they’re discovered, unless we go back to visit them (or if we are site stewards, entrusted with the responsibility of routine monitoring). I recently did so, and it was not the fond reminiscence I was expecting. Here’s my experience.

Between 2006 and 2009, and with the help of many volunteers, I surveyed over 1,000 acres of South Mountain Park, in Phoenix, as part of my preservation fellowship. We recorded over 100 new archaeological sites, with the vast majority including Hohokam petroglyphs. Because it usually lies exposed to the elements, and since it attracts such attention (as it was typically designed to do), rock art is particularly prone to erosion, vandalism, and theft. Petroglyphs in the South Mountains are no exception, especially given their proximity to the sixth largest city in the U.S. Graffiti and other types of vandalism have plagued the South Mountains for well over a century. The earliest dated graffiti we found was from 1902, with earlier dates probably lurking about in unsurveyed areas. With an estimated four million visitors each year, managing the thousands of petroglyphs and other cultural resources in South Mountain Park continues to be monumental challenge, and will likely remain so for many years to come.

A few weeks ago, I decided to revisit a couple of the petroglyph panels we recorded a decade ago. I was hoping to get some new, higher-resolution photographs, and I was really anxious to see one of the more impressive and interesting panels, which bears over 70 petroglyphs on a single face.

Words can’t capture the disappointment I felt when I turned the corner and saw the scream of bright pink paint on this once-pristine petroglyph panel. It’s apparent that the graffitist attempted to avoid covering any of the petroglyphs, placing their tag at the far top left of the boulder rather than smack dab in the middle. Their aim was off, though, and the pink hideousness still covers part of one of the glyphs.

Why this panel was targeted is a mystery. The site is difficult to access, and this panel isn’t visible from any trail or vantage point—both of which help explain why it has remained in such great condition for so long. Furthermore, this pink paint does not stain any of the other rocks in this area. So, it seems that the graffitist intentionally ventured into the South Mountains to paint on this specific panel. It was a deliberate act, with a premeditated victim in mind. First-degree petrocide.

Not long after that, I made another trip to the South Mountains to experiment with the Rock Art Stability Index . I had a particular panel in mind because, from my records, it exhibited an assortment of natural and anthropogenic impacts. Even though it’d been seven years since my last visit to this site, I was certain of its location.

As I walked up to the panel, all I saw was a dark rock face.

The glyphs I remembered being there had disappeared. Noticing the large spalls (known to geomorphologists as scaling) on the panel, I quickly concluded that the glyphs had been chiseled off and stolen, something I had documented elsewhere in the park. But as I peered closely at the panel, I started to make out a number of really faint petroglyphs. The first was one of a scroll I remembered.

Then I noticed the distinctive circle-bodied lizard,

and then one of the classic Hohokam stick-figures.

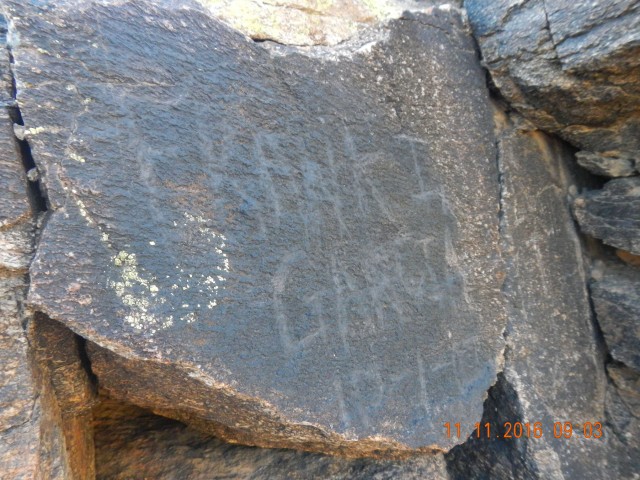

The panel had been sprayed in black paint. Looking down at the ground, I even noticed black droplets from where someone’s finger had blocked the spray of the paint.

Again, I was left scratching my head, wondering why. Looking at the pattern of spray paint, I couldn’t discern any names, initials, or graphic illustrations as is common for graffiti. No, the black paint was only found on top of the individual petroglyphs, as though they were close-range targets. In this case, and unlike the painter of pink graffiti noted above, the graffitist deliberately attempted (and mostly succeeded) at blacking out the Hohokam petroglyphs. They also blacked out the 1902 inscription noted above, which is ironically also found at this site and is now legally considered an historic property and entitled to protection under Phoenix’s Historic Preservation Ordinance (opens as a PDF).

Did someone think these petroglyphs were graffiti, and take it upon themselves to “clean up” the park? Or did they want to erase evidence of prehispanic presence on this landscape?

Without apprehending the graffitists, we’ll probably never know why they did what they did. What we are certain of is that the actions of these few have damaged something appreciated by many, something sacred and revered by the Native American communities who consider these Hohokam artists to be their ancestors.

2 thoughts on “Disappointing Discoveries”

Comments are closed.

what training and resources such as trained volunteers would be required

to restore these precious markers and symbols ?

Hi, Larry,

Aaron sent this reply from the field:

Good questions, Larry. It is the responsibility of land managers to protect the cultural resources under their stewardship, and to use conservation methods when deemed suitable and appropriate. Rather than attempting to clean the graffiti ourselves, it’s advisable to report vandalism to the land manager so they can take the appropriate measures. The South Mountains are under the keen stewardship of the City of Phoenix, which has a graffiti removal program that is actively involved in removing spray paint from petroglyphs in the South Mountains. Such work is carried out by trained conservators, who use state-of-the-art methods and techniques (see, for example, Tim Roberts and Wanda Olszewski’s recent article in Archaeology Southwest Magazine 40, pg. 30). It is important to recognize that while there are ways to remove most paint graffiti, there is no way to erase graffiti is impressed into the rock face (scratching, abrading, chiseling, etc.). We cannot restore rock or desert varnish that has been removed. There have been some attempts to use stone-colored paint to mask such graffiti, but over time such paint fades and weathers, often resulting in an unsightly mess that is more of an eyesore than the graffiti itself.