- Home

- >

- Preservation Archaeology Blog

- >

- For Posterity

(July 11, 2017)—My Intro to Archaeology instructor once told me that an Archaeologist is only as good as the notes he or she takes. (Well, actually, it wasn’t just once.) I have had that statement repeated like a mantra ever since I began my coursework in the field.

With no humility in this statement whatsoever, I have always received high marks in writing and penmanship. In addition, I have always loved to draw. Unfortunately, due to college and work and the consistently busy life of someone in their early twenties, I don’t usually get the opportunity to write and draw freely.

This field school presented me with a unique opportunity. I was embarking on a trip to a place I had never been before, doing something I had never done before (yet always dreamed of), and working in a field that embraces tedious note-taking. To top it all off, keeping a journal would, if nothing else, be a fun and productive way to pass any free time at camp—although most of the time there wasn’t much of that to be found.

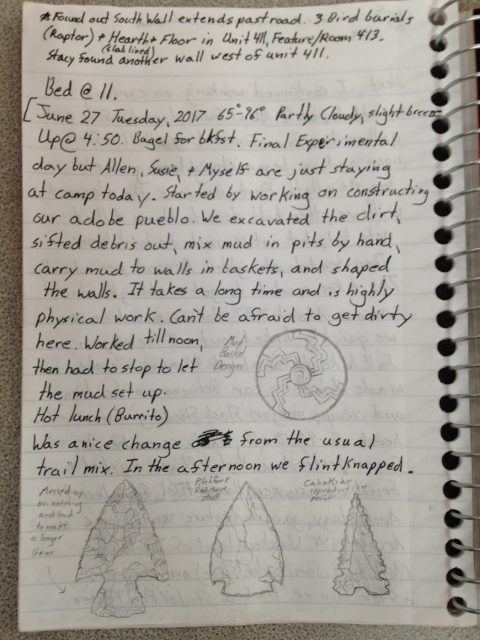

So, in a small black five star journal worth 75¢, I began recording what would be a priceless experience. I would make an entry for every day, but on the first, having never successfully kept a journal before, I was at a loss on what to include. The date, high and low temperatures, weather, what time I went to bed and what time I got up, and what I had for meals all seemed like reasonable things to start with. Next, I would add whatever seemed important on that particular day. My perception on what exactly defined important would change quite a bit over the course of our summer. Entries would fluctuate in length and detail, as well. Early ones (and on nights when I was dead on my feet after a tough day) may have been only a half page or so, whereas others could take up four or five.

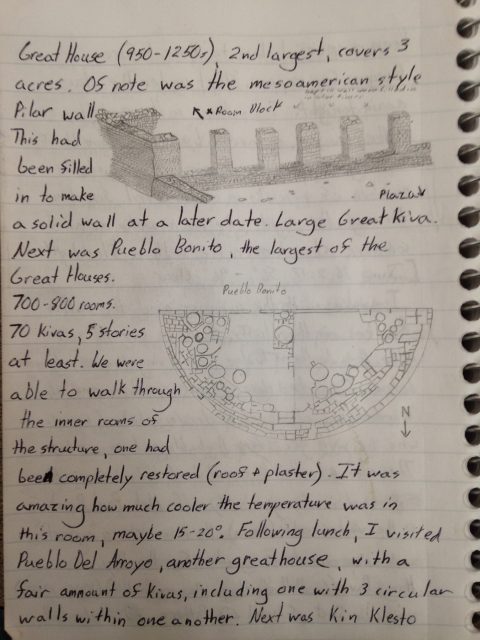

I described the sights and sounds of trips to places like the towering Gila Cliff Dwellings, the magnificent Chaco Canyon, and the KOA Campground in Grants, New Mexico. I recorded meaningful conversations with PhD lecturers and locals alike. Perhaps most importantly, though, I did my best to describe every significant (and many insignificant) finds in not just my own unit, but also throughout the whole dig site. Even though this information was being officially recorded in site forms and maps, something felt right about recording it for me, as well.

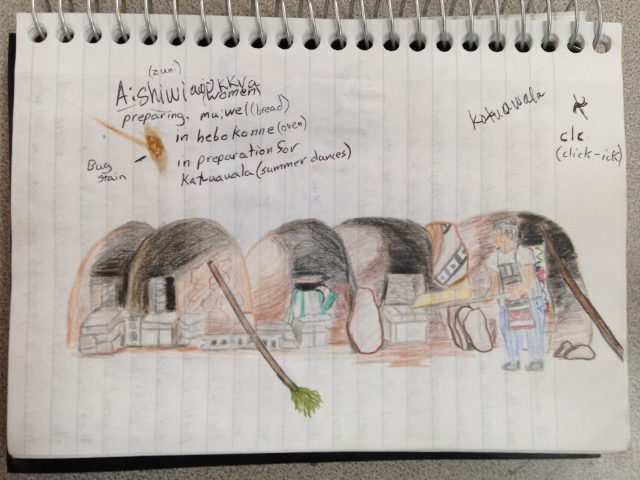

I did, however, feel as though something was lacking in my journal after a few days. Of course this was illustrations. Who would ever want to just read boring old text, right? Although I had experienced all things firsthand, other potential readers would likely not be as lucky. If nothing else it was a good excuse to doodle. I illustrated the cliff-top city of Acoma, an array of projectile points that I knapped myself, Zuni women baking bread in preparation for the summer dances, and the layout of adobe walls which had laid buried for hundreds of years, just to name a few.

As I am nearing the end of this field school, I reflect back on many of the amazing experiences I have had. Though many are still fresh in my mind and vivid, I realize that we only hang on to a select few memories, and these can often be twisted by time. My journal entries, though, will remain exactly the same as the day I wrote them, until such time as the ink fades from the pages.

Explore the News

-

Join Today

Keep up with the latest discoveries in southwestern archaeology. Join today, and receive Archaeology Southwest Magazine, among other member benefits.