- Home

- >

- Preservation Archaeology Blog

- >

- Shell Bracelet Manufacturing

Christine H. Virden-Lange, Desert Archaeology, Inc.

(September 27, 2017)—In the ancient United States Southwest, the culture group archaeologists call the Hohokam inhabited the area from northern Mexico on the south to the Colorado River on the west, the Agua Fria to the north and the Gila River to the east. From about A.D. 50 to 1450, these people were known for their ornaments of personal adornment, especially those manufactured from marine shells collected from the Gulf of California, with a minor amount from the Pacific coastal waters off southern California.

Beads and pendants made from whole shells and ornaments made from cut or ground shells were quite popular throughout the Hohokam era. But the ornament form that sets the Hohokam apart from other groups is the shell bracelet, which was made from the Glycymeris shell, also known as the bittersweet clam.

The two primary species of Glycymeris shells that have been identified in the archaeological record include G. gigantea and G. maculata. G. gigantea, the larger of the two, seems to be confined to the Gulf of California area, from Bahía Magdalena, Pacific coast of Baja California Sur, and into the Gulf of California as far north as Bahía la Choya, Sonora, while extending to Puerto Marqués, Guerrero, Mexico. We can distinguish this large clam shell from other species by its cream-colored shell with brown blotches and zig-zag bands or chevrons, or both.

G. maculata is also found in the Gulf of California, as far north as near its head at Puerto Peñasco, Sonora, Mexico, extending to Islas Guañape, La Libertad, and south to Perú. This species is slightly smaller than the G. gigantea, with an exterior shell that is also cream colored, but the markings are irregular pastel brown blotches with some brown zig-zag patterns on the beaks of the shells.

Pretty straightforward, right? The species are distinguished from each other by the brown markings on the exterior of the shell and by size. But in an archaeological ornament collection? Then it is much more difficult to distinguish them, because the shell has been greatly reduced during the bracelet manufacturing process, removing virtually all of the brown patterning that would set them apart. Moreover, people chose dead shells—white beach-drift specimens—if fresh ones were not available. We can’t necessarily identify them by size, either—thinking that a very large bracelet band must be a G. gigantea, for example—because it is possible to stumble across a large G. maculata. And it is impossible to know how much of the exterior edges of the shell (the margins) were removed (reduced) as the band was made.

Archaeologically, bracelets first appear in the Santa Cruz River valley during the Early Ceramic Period (A.D. 50–500) in small numbers. These bands were very gracile and plain, with the beak (umbo) greatly reduced or even ground away. They appear in conjunction with clay containers, both possibly arriving from La Playa, a site located just south of the international border in northern Mexico, where a thriving shell jewelry manufacturing tradition was already in place.

Almost overnight, the bracelets became a popular commodity—everybody wanted one! Soon, Glycymeris bracelets became associated with those identified as Hohokam, along with a suite of other artifact forms such as red-on-buff ceramics, ¾ groove axes, other shell jewelry, ground stone palettes, and particular rock art motifs.

How to make a bracelet

First, unless you know someone who has a shell collection, you must obtain the shells yourself by traveling across the international border with Mexico, and continuing south to the Gulf of California to the area around Cholla Bay and Rocky Point. You should be able to find some shells as you stroll along the beach. If they have colorful exteriors, then you know they are fresh shells. If they are white, beach-drift specimens, then you know they are older, dead shells. If the shells have lost their coloration and are sort of gray looking with a sand breccia matrix on the interior, they are probably fossil shells. The latter are very dense and difficult to work, and they break easily—not good for making a bracelet! Some of the shells might have an abundance of small holes, which result from small sea worms boring into the shells. These holes weaken the shell, which may cause it to break easily during the manufacturing process. In other words, you will need several shells as back-ups!

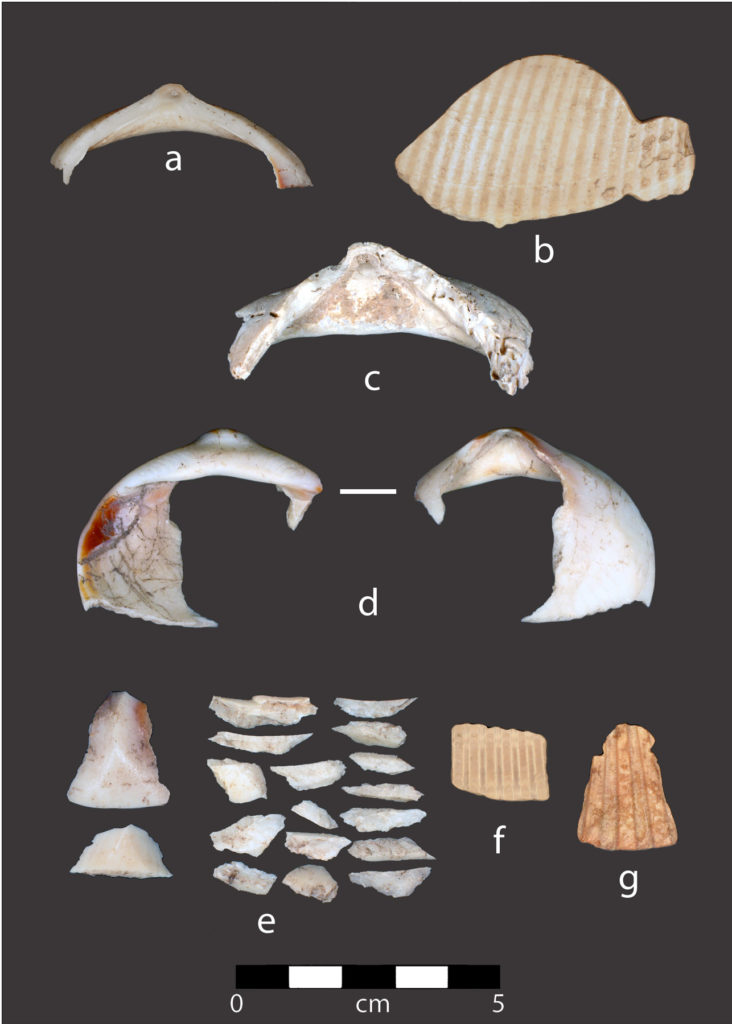

Archaeologists have identified three known bracelet manufacturing methods in the archaeological record. Emil Haury described the method Snaketown’s artisans used: they removed the highest part of the convex surface of the Glycymeris valve by grinding it on an abrasive surface (such as a lapstone of sandstone) until they were able to punch a small hole through the thinned surface. People then expanded the diameter of the opening by chipping. If the valve wall became too thick for successful chipping, more grinding thinned the shell and provided the edge which made further chipping easy. The roughed-out shell circle could then be finished by using a rasp or reamer (ground stone tools) or both to smooth the inner edge. Archaeologists recognized early on that this method was distinctly Hohokam. It creates some shell chips and a lot of white shell dust.

The second method is known from the La Playa site in northern Sonora, Mexico. The upper surface on the shell exterior was marked off with deep, regular, short scratches as the artisan sawed with a sharp flaking tool. The grooves on the exterior were even and straight-edged, whereas from the interior the cores appear rough-edged. When the artisan felt the grooves were deep enough, he simply tapped the center with his hammerstone and the core fell out, splintering the underside in the process. After removing the center core, the manufacturer ground the ragged edges of the roughed-out bracelet with tools such as reamers and smoothed the bracelet band with fine-grained stones. This process produces a core with a distinctly grooved edge. The majority of the cores recovered from La Playa had been produced using this method.

The third method entails grinding the back of the valve at various points to thin the shell, then chipping or punching out the central core, leaving the core with a faceted appearance. Although only a few specimens of this type of core were found at La Playa, this method of valve reduction appeared to be used by artisans in the Papaguería area at sites such as Ventana Cave and Gu Achi. Archaeologists recovered two cores that probably resulted from this method at the site of La Villa in Phoenix.

The outer marginal edge of the bracelet bands had several different styles of treatment, as well. In some cases, the exterior was left in its natural state, giving the bracelet band a low triangular profile. Other bands had the outer margin steepened by chipping back the marginal edge, then grinding it smooth to a more vertical profile. This method produces small pieces of chippage that archaeologists sometimes find. Some artists chose a more rounded look for their bands, using a series of grinding and polishing sequences to achieve the desired look. The byproduct of this method is a highly polished band, sometimes with striations visible on the surface. Bracelet bands collected from individual sites show that artisans would tend to follow whatever local tradition was popular at the time.

Stylistic differences through time

Emil Haury first observed the ubiquity and transformation of shell bracelet bands as they changed through time based on the artifacts recovered from multiple excavations at Snaketown, which is located north of the Tucson Basin and near the middle Gila River. People lived at the large site for generations, and it had many pithouses, a ballcourt, and canals, as well as an abundance of artifacts.

Haury noticed that the width and thickness of the bands increased through time beginning in the late Pioneer period (A.D. 700–750), and extending through the Colonial period (750–950) into the Sedentary period (950–1150). The wider bracelet bands were dominant in the Sedentary period and carried on into the Classic period (1150–1450). These later, bulkier bands had little, if any, modification of the umbo. The greatest experimentation of embellishment on the bracelets occurred during the Sedentary period. Occasionally, artisans modified the umbo by grinding it flat and perforating it, perhaps to hang something from it, such as a feather or beads.

Life forms represented in shell did not appear until the advent of shell bracelets. Although modifying the bands began during the Vahki phase of the Pioneer period (A.D. 500–650), it wasn’t until later on into the Colonial and especially the Sedentary periods that carving decorations on the bands became significant. Beginning with simple geometric designs of parallel lines or chevrons along the exterior of the bands, artisans then began transforming some of the bands into snake motifs, carving the bands to portray the undulating motion of a snake. The arrangement of the elements included head-to-tail, head-to-head, and tail-to-tail.

Some motifs, such as frogs, were carved in high relief. Combining a bird and a snake was a favorite motif during the Colonial period and into the Sedentary period. The frogs were incorporated into the roundness of the umbo, with the beak of the umbo serving as the mouth/nose of the frog. Sometimes, artisans would also carve appendages on the sides of the umbo. Occasionally, the eyes of frogs, birds, or snakes would be inlayed with small pieces of turquoise.

Explore the News

Related to This

-

Culture Hohokam