- Home

- >

- Preservation Archaeology Blog

- >

- Northeast Syria: From Mofunland to Rojava

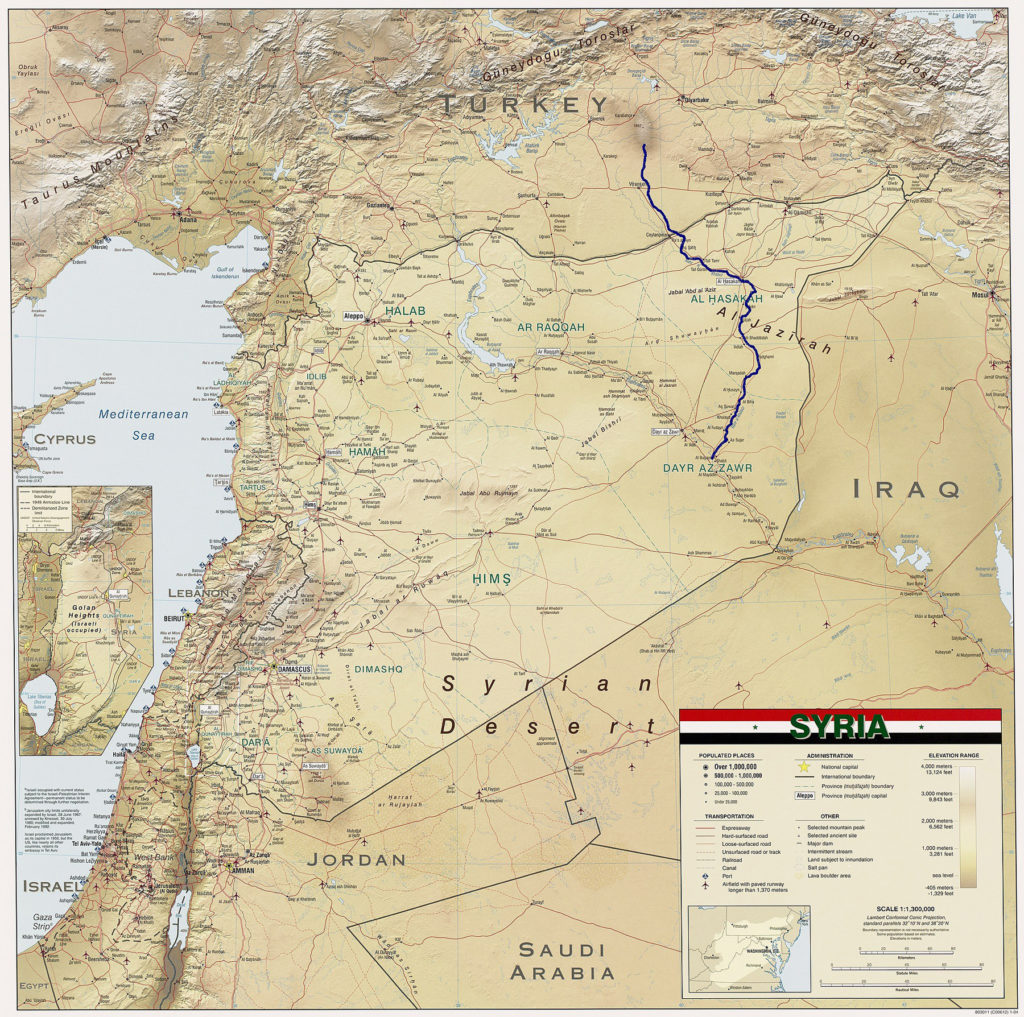

(May 3, 2018)—Back in the late 1980s and early 1990s, I had the opportunity to spend three field seasons excavating Bronze Age sites in northeastern Syria. For you Google Earth explorers, the sites are located in the Habur River drainage between the modern towns of al-Hasakah and Qamichli. At the time, Hafez al-Assad’s Syria was firmly in the Russian orbit and well off the beaten path of Americans.

Once in-country, western Syrians from Damascus and Aleppo thought we were “majnun” (Arabic for crazy) for heading to the “Wild, Wild East.” If Syria was the middle of nowhere, we were heading to the middle of f—ing nowhere, which we soon gave the affectionate nickname Mofun-land.

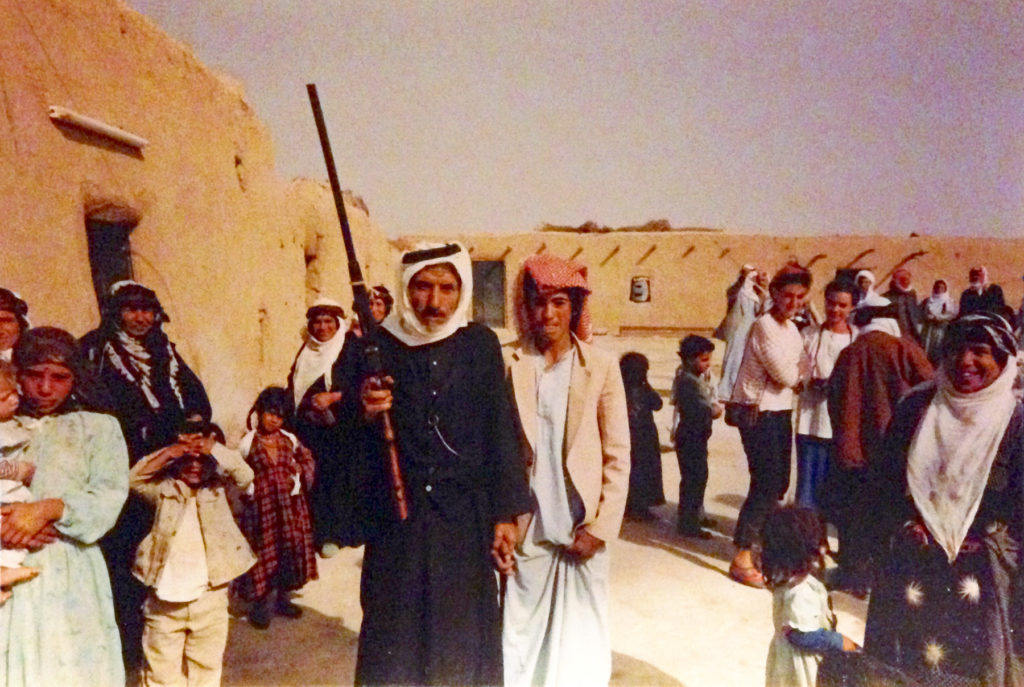

Over the course of a total of about six months in Mofunland, I developed a deep respect for the way things were run. The Kurds were the majority group, but there were also many other persistent ethnic groups with deep histories in the region, including Arabs, various Turkmen tribes, Circassians, Armenians, and Assyrians. A number of religions crosscut these groups, including various branches of Islam and Eastern Catholicism. There were also Yezidis and even a few Zoroastrians practicing the world’s oldest monotheistic religion. Through an intricate web of relations that would take a lifetime to understand, all these various ethnic and religious groups managed to get along with minimal violence and little government intervention.

Each village or village cluster had a leader (Mukhtar) who was chosen by the people. I got to know one Mukhtar largely through his son, who was one of my workmen. He was a courageous and shrewd man who had a reputation for being fair and wise, which is why the people chose him. Councils of Mukhtars from the same tribe or district made consensual decisions after hard bargaining. At the time, the Syrian government wisely kept its eye on, but its nose out of, local affairs.

I remember one example of tribal conflict resolution vividly because we were told to remain in our camp one day for our safety. A woman from one tribe left her husband and ran off with a man from another tribe. The couple sought asylum in a Syrian police station. The story I heard afterward was that all the men from both tribes showed up at the station. After a short standoff, the police pushed the couple out the door. They were summarily executed and “given to the dogs” so they couldn’t receive formal burials. Brutal but efficient: sacrificing one member of each tribe to avoid a protracted feud that would have cost the lives of many. We went back to work the following day as though nothing had happened—it was never mentioned again and as far as I know it never happened again while we were there.

Through a complex web of arrangements, Mukhtars also acted collectively for mutual economic benefit, including harvesting, sheep-herding, hiring work crews, and even sharing oil revenues. Because the success of the Mukhtar was closely tied to the well-being of a relatively small number of people, there wasn’t much room for aggrandizement. Although bribes were common practice, these were considered an integral part of the economy, rather than a crime.

Because of the deep affection for the Syrian people I developed 25 years ago, I have closely followed ebb and flow of the Arab Spring and subsequent Syria Civil War with an admitted bias toward the more moderate rebel factions. After five years of horrific violence, northeastern Syria is now a self-proclaimed autonomous region called Rojava (aka Democratic Federation of Northern Syria, or DFNS). If you haven’t heard of Rojava, you should Google it. It is one small beacon of hope in an otherwise desolate landscape.

Rojava has been a de facto ally of the United States for more than three years, providing most of the foot soldiers and suffering most of the casualties in the fight against Daesh (ISIS) in Syria, which recently culminated in the capture of Raqqa, the de facto capital of ISIS. American special forces are embedded in Rojava militias and both closely coordinate American air strikes.

Rojava also is a fascinating sociopolitical experiment within a multicultural and religiously pluralistic setting. At the heart of Rojava political organization is one of the most participatory and inclusive democratic constitutions (called a social contract) crafted in quite awhile. This contract is an interesting blend of democracy, anarchism, and ecology. It recognizes the fundamental rights of gender equality, as well as freedom of cultural and religious expression. Not only are these rights guaranteed at the basic citizen level, but are also embedded in the political structure through the practice of “co-governance,” where one member of each major ethnic group and at least one female are among the top officers of each decision-making body. In some ways, this organization hearkens back to the old Mukhtar system, except that it is more pluralistic and less patriarchic.

Rojava is one polity that holds the social sciences in high regard—a breath of fresh air to many of us practitioners! Rojava political doctrine draws heavily on the work of Murray Bookchin, a pioneer in the social ecology movement, who was a strong advocate of “bottom-up” democracy focused on local citizen assemblies connected in a loose confederation. This has resulted in the establishment of hundreds of self-governing village and neighborhood communes throughout Rojava that are committed to environmentally sustainable practices. Perhaps we could learn a few lessons from them.

The Rojava political system has been called a democracy without a state and compared to Athenian democracy and the Swiss Canton system. Rojava districts are even called cantons. Local councils and committees comprised of representatives are in frequent contact with their constituencies. The representatives meet regularly to discuss relevant issues and make decisions. These councils communicate with each other to organize more collective action such as defense. There is little need for a strong central government, and people think for themselves and debate relevant issues in public spheres, rather than relying on mass media to shape their views. The few journalists, military volunteers, and other adventurous Westerners who have spent some time in the region have remarked on the high confidence level, knowledge of current events, and strong freedom of individual expression demonstrated by Rojavans.

Considering the ethno-religious diversity of the region, Rojava political organization is by definition inclusive. In an ideal world, it could serve as a model for unifying Syria, one of the most ethnically and religiously heterogeneous countries in Southwest Asia, in a manner that respects and represents all groups. From my own research perspective, Rojava is a very intriguing experiment in coalescence as we have used the term in our Salado research. If left alone, it will be interesting to see how Rojava plays out, especially regarding its ability to integrate Arabs who often view Kurds as second-class citizens.

Unfortunately, external forces might ultimately decide Rojava’s fate. Rojava is squeezed between Erdogan’s Turkey and Bashir al-Assad’s Syria supported by Russia and Iran. Both regimes arguably base their actions on “might makes right” with little regard for human life, let alone rights. As a testament to the complex social networks of the region, Syrian Kurds also have close links with Turkish Kurds, including members of the Kurdish Workers Party (P.K.K). Thus, from an American perspective, Rojava is a stateless polity that is both a close ally and a sponsor of a terrorist organization in another ally. Could it get more confusing?

Sure it can! In the wake of Daesh’s collapse, Russia also is establishing closer ties to Rojava as a buffer to Turkey. The recent fall of the Afrin Canton to pro-Turkish “Syrian rebels” underscores the perilous position of Rojava. A highly motivated and battle-hardened militia and American air support are the only things keeping Rojava from being overrun, and now that Daesh has been nearly eradicated, this support might evaporate.

I hope my post generates enough interest among a few readers to keep an eye out for future developments in this forgotten, but very pertinent, corner of the world. It is no longer Mofunland among the power circles in Moscow and Washington, but a potential flashpoint for a wider conflict. At the very least, we owe Rojavans our consideration for their role in nearly eliminating Daesh in Syria. Since Turkey bombed the central media station (ARA Pulse of the North) in late 2017, forcing it offline, news out of Rojava has been sparse. (There was, however, a recent post on the DFNS Facebook page about the opening of a parliament building in the town of Derik.)

To learn more about recent virtual archaeological survey of the Upper Khabur Basin, check out the work of Dr. Jason Ur and colleagues.

One thought on “Northeast Syria: From Mofunland to Rojava”

Comments are closed.

Explore the News

-

Join Today

Keep up with the latest discoveries in southwestern archaeology. Join today, and receive Archaeology Southwest Magazine, among other member benefits.

Dear Jeff Clark

Thank you very much for your suggestive report on Rojava and its archaeological heritage – I read it only after my brief visit in October 2021, when the situation was still as you describe, even under covid19 lockdown. Since 15th December it seems to have turned more critical.

Archaeological restoration work has continued at a modest but hopeful way, in the same manner of goodwill to comply with new standards.

We may have met n the early 90ies when also Tony Wilkinson was working in the Balikh region.

Claus-Peter Haase