- Home

- >

- Uncategorized

- >

- Comparing Community Histories at Chacoan Outliers�...

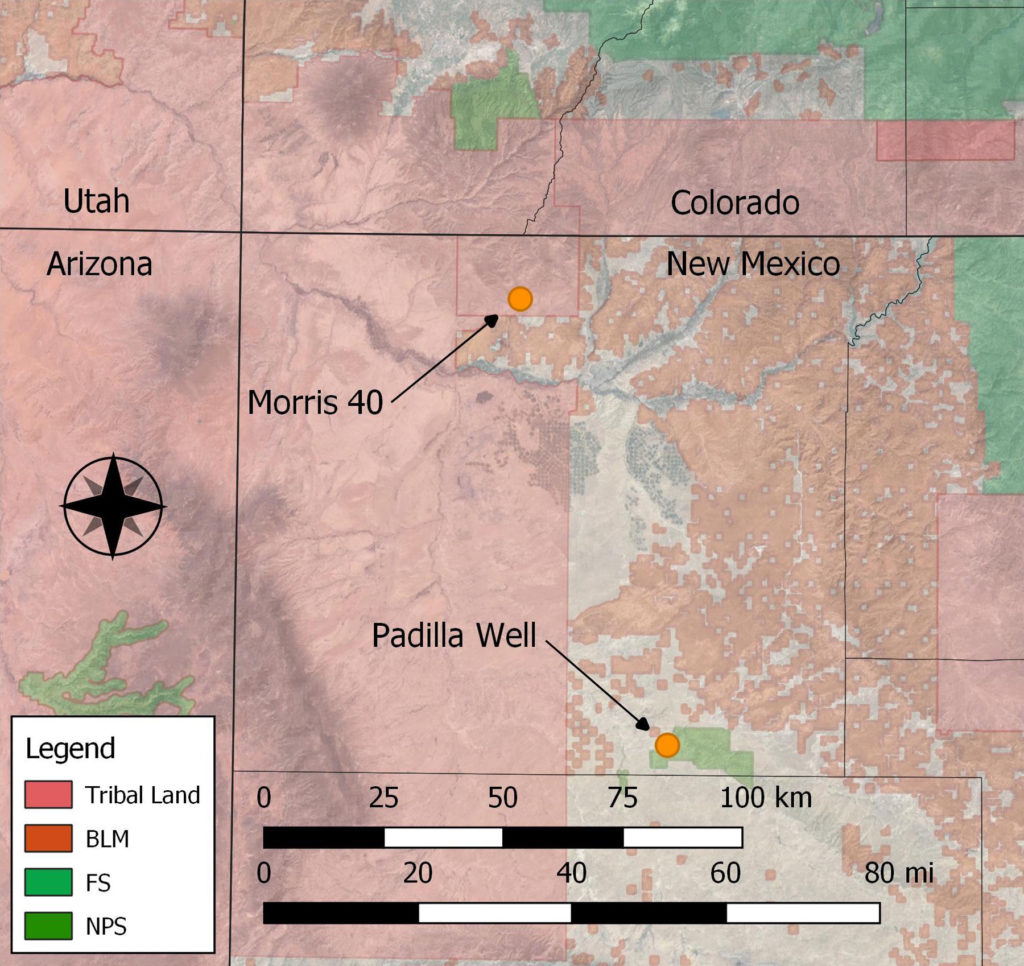

(May 9, 2018)—Given that recent research keeps pushing back the dates of the really interesting things that happened in Chaco Canyon (macaws at AD 900! venerated leaders by AD 850!), it seems like it might be time to take a good look at the Early Bonito Phase (AD 840–1020) across the San Juan Basin as a whole. Over the past forty years, John Stein, Michael Marshall, Ruth Van Dyke, Thomas Windes, and others have identified numerous outlier great house communities with origins in the 800s (and earlier). For my dissertation research with Dr. Van Dyke at Binghamton University, I am comparing community development at two of these outlier great house communities in New Mexico—Morris 40 and Padilla Well.

A focus on the Early Bonito Phase could accomplish some important goals in Chacoan research:

First, what was different about ninth- and tenth-century communities in the Chacoan Core? Were there specific “conditions of possibility” here that encouraged the development of monumentality on a scale beyond that of other regions? Other places had big, early settlements (South Chaco Slope, I’m lookin’ at you!), but they do not seem to have developed the kind of integrated cultural landscape that characterizes Chaco Canyon itself.

Second, there has been a lot of chatter over the past ten years about the relationship (or lack thereof) between Mesa Verde Pueblo I villages and early Chacoan great houses. Some folks—full disclosure, I’ve been one of them—argue that people leaving (fleeing?) the collapsing villages in and around the Dolores valley moved south and instigated the construction of several early great houses in the San Juan Basin. A focused research plan evaluating the Mesa Verde migration hypothesis is in order.

To address these questions, I’ve conducted fieldwork at two San Juan Basin Chacoan communities with significant Early Bonito Phase components: Morris 40 and Padilla Well. Last August through November, I, several Binghamton University graduate students, and a group of several Southwest archaeology notables mapped roomblocks, completed geophysical survey, and recorded artifacts at these two communities. In this post, I’ll describe our efforts and give a few preliminary results.

Morris 40

Morris 40 is located in a remote corner of the Ute Mountain Ute Reservation in New Mexico. (This portion of the project occurred with the full permission and support of the Ute Mountain Ute Tribe.) The community occupies the narrow piedmont at the foot of the New Mexico hogback, a striking Cretaceous monocline that forms the northwestern edge of the San Juan Basin. At the base of the monocline, cottonwoods mark the location of springs that form as water cascading down the slickrock tumbles through slot canyons into secret sandy pools where sandstone meets steppe. To the southeast of the community is The Meadows, grassland dotted with the genuflecting derricks of the Verde Oil Field. The San Juan generating station looms on the southern horizon.

Ancient habitations cluster on either side of an incised arroyo that cuts through the hogback. Once upon a time, the debouchment of this arroyo fed a permanent spring crowded with cottonwoods, though today the spring is dry and the most prominent vegetation is greasewood and a monstrous thicket of tamarisk.

Euro-Americans have known about the site since the 1870s—it received a small dot on Hayden’s 1876 map of the Four Corners. Extensive pothunting happened in the 1890s, and Earl Morris worked at the site very briefly in 1916 (he called it Navajo Springs, then later gave it the “Morris 40” moniker). Deric Nusbaum mapped and documented the community in 1935, and his notes have been invaluable for identifying roomblocks destroyed by oil development between 1956 and the early 1960s. Cultural resource management work in the 1970s brought the community to the attention of Chacoan archaeologists (at which point it was dubbed “Squaw Springs”), and a seismic survey by Woods Canyon Archaeological Consultants in 2014 is how I first learned of it.

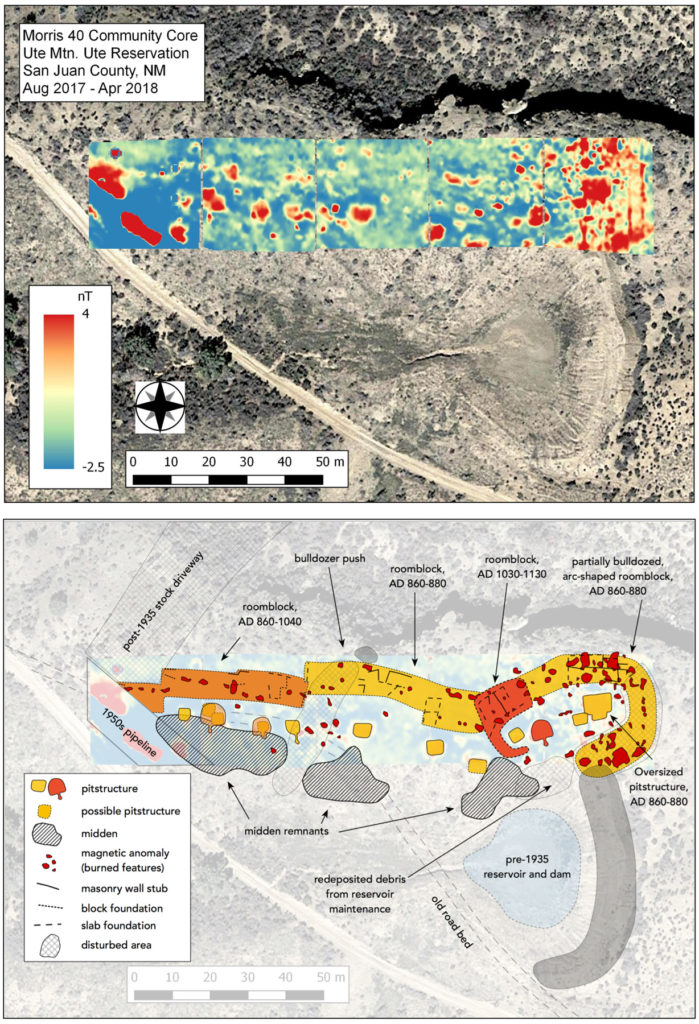

I sought to build on the Woods Canyon work at the site by completing systematic ceramic and lithic counts (Dean Wilson, Lori Stephens Reed, Tim Kearns), further documenting the architectural variation within the community (me), and conducting magnetometer surveys to look for buried structures hinted at by surface features (Hunter Claypatch, Daniel Leja, Joshua Jones).

Morris 40 began as an Early Pueblo I village in the late AD 700s or very early 800s. During the mid-to-late 800s, the community expanded significantly and its inhabitants constructed two long lines of roomblocks (and a couple shorter ones). Over 400 meters of identifiable surface architecture suggests a population of at least 200 or 300 people. Magnetometer survey identified about 14 pithouses within a 150-meter section of this classic Pueblo I village. Throughout much of the 900s and early 1000s, the community pattern largely adhered to the original Pueblo I village layout, though many of the original post-and-adobe or jacal portions were probably falling into significant disrepair and not used for habitation.

Around 1050, a series of striking changes occurred. A large structure pre-dating the great house was razed. The architectural debris was mixed with midden deposits and used to construct a “platform mound” on which the two-story great house was constructed. The old roomblocks at Morris 40 that had been inhabited since the late 800s were mostly abandoned in the later 1000s, and a new neighborhood was constructed south of the great house and west of a deeply incised Chacoan road segment. The road segment can be traced on LiDAR datasets for nearly a mile to the south, at which point it diverges into two branches. One of them points within a few degrees of the massive Waterflow petroglyph site that is still visible on the north side of Highway 64.

Despite the advantageous location, the community contracted significantly by the mid-1100s. In this sense, it tracks more with the political developments of the San Juan Basin than the Mesa Verde region, despite participating almost exclusively in Mesa Verde ceramic exchange networks (there are precious few Cibola or Chuskan sherds at the site). Following a probable hiatus, a few roomblocks were re-inhabited during the Pueblo III period, probably after 1225, because they had fairly large proportions of Mesa Verde Black-on-white relative to McElmo Black-on-white.

A more extensive Pueblo II community exists throughout The Meadows, though we did not visit these sites during this project. Future work will hopefully investigate the relationship of these smaller community sites to the community core surrounding the great house.

Padilla Well

Padilla Well lies at the extreme western edge of Chaco Culture National Historical Park. The Navajo Reservation is just a stone’s throw to the west. Getting to Padilla Well involves a long drive east from the Lake Valley Chapter, following two-tracks that, to the uninitiated, all look the same and seem to go nowhere in particular. After a few conversations with the Navajo families that live and use the allotment lands west of the National Park, however, the subtle but deep cultural geography of the rolling grasslands and shale-sided buttes along Chaco Wash begins to take shape. Though the two-tracks all look the same, some are major thoroughfares, others minor arterials, with the distinction between the two a function of time, weather, and changes in the demography and ecology of the eastern Navajo Reservation. Our path led across a deeply entrenched southern tributary of Chaco Wash, the route marked by a prominent segment of pipe wedged in the arroyo bottom to facilitate getting across.

Though today nobody lives at Padilla Well (a cottonwood-shaded oasis that is actually a mile north of the great house), the crumbled hogan foundations are still visited by descendants of the family that originally built them in the late 1800s. With their permission, we established a base camp south of their old homestead just outside the National Park boundary.

Our canvas-walled storage tent and tarp ramada resembled field camps of the early 20th-century Tozzer and Farabee expedition, which passed through this section of Chaco Wash. Though neither Tozzer nor Farabee mentioned the Padilla Well great house, it must have been visible as Richard Wetherill led them to the edge of West Mesa in the summer of 1901 and oriented them to the landscape. From the great house, the mesa completely fills the eastern horizon, and the human-height cairns that mark the shrine at the mesa’s edge loom like sentinels above the Padilla Wash valley.

The first definite mention of Padilla Well was in the 1950s, when Gordon Vivian recorded the location of a cluster of ruins during a reconnaissance of this section of the park. Twenty years later, the Chaco Project completely surveyed the Padilla Wash valley and documented the great house. It was mapped and recorded several times over the next 40 years, by Michael Marshall and Anna Sofaer in the 1980s, and again by Tom Windes and several volunteers in the late 1990s.

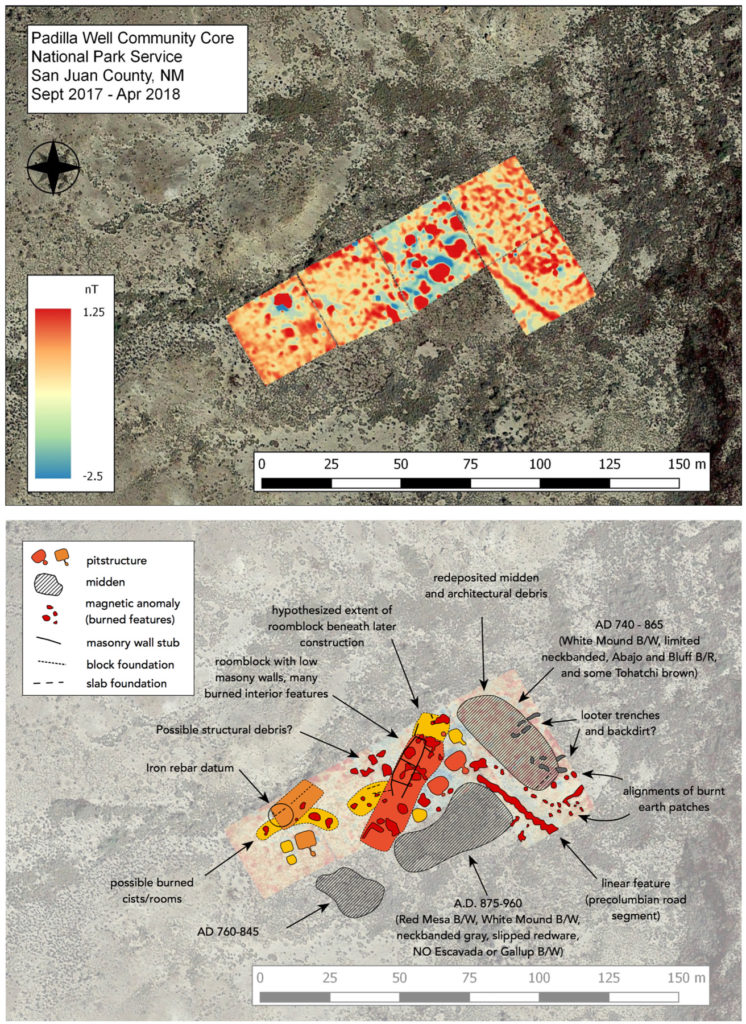

Our work was intended to follow upon that of Tom Windes, and particularly to use geophysical survey to evaluate the extent of architecture at several Pueblo I and early Pueblo II roomblocks that he described. For eight days in September, we mapped numerous roomblocks in the community core (me) and made detailed observations on construction materials (Ruth Van Dyke), surveyed grids atop architecture with the magnetometer (Hunter Claypatch and Daniel Leja), and recorded ceramic and lithic artifacts (Dean Wilson and Joshua Jones).

Ceramic evidence suggests that Padilla Well was first occupied in the mid to late 700s. Between about 740 and 860, people lived in single household habitation units that were loosely clustered. At the south end of the area we documented, however, there may have been a larger multihousehold roomblock that was obscured and dismantled by later construction.

From 860 until about 1000 there were four main habitation areas. Magnetometer survey over one of these revealed a complex history similar to the small sites excavated by the Chaco Project in the 1970s (e.g., 29SJ 699 and 724). Around 875 or 900 people razed an earlier Pueblo I structure and built a relatively large adobe structure in its place. The architectural debris and midden fill of the earlier structure was then redeposited as a mound east of the new structure with a retaining wall on its south end. A possible early road segment, pointing towards a Red Dog shale source high on West Mesa, separates this constructed mound from the trash and burial mound that was actually deposited during people’s use of the structure. Late in the building’s history, the inhabitants may have undertaken a remodel, adding masonry walls that seem offset from the original adobe structure foundations. All this must have occurred between about 875 and 960 or so, as the midden associated with this structure contains White Mound and Red Mesa Black-on-white, but no Gallup or Escavada Black-on-white and no Chuskan wares.

People built the great house around 1050 atop a structure that was not necessarily the most impressive building in the community. A great kiva was constructed about the same time and linked to the great house via a short road segment lined with sherd-filled berms.

The community waned in the early 1100s and people may have left entirely by 1150. In the very late 1200s, however, a new structure with a tower was built east of the great kiva. This building is associated with Mesa Verde-style white wares and copious amounts of very late St. John’s Polychrome. We located a few pieces of Springerville Polychrome across the site, too, corroborating the fact that there was a late, brief reuse by one or two households that may be associated with the demographic upheavals of the late 1200s.

We suspect that we only documented about half of the Padilla Well community core. Reconnaissance revealed several additional Red Mesa phase roomblocks to the south. Chaco Project survey in the 1970s indicated a larger dispersed community within the Padilla Wash valley. With future work, I hope to explore the relationship of this community hinterland to the core surrounding the great house.

Linking Fieldwork to the Bigger Issues

Comparing Padilla Well to Morris 40 reveals more differences than similarities, I believe. Yes, they both had great houses by the mid-1000s; yes, these great houses were integrated into a larger cultural landscape of roads, shrines, and great kivas. But the Padilla Well Chacoan landscape appears to have been a largely autochthonous creation that began as early as 875. In contrast, the Morris 40 Chacoan landscape was imposed on an existing community circa 1050, and this probably involved uprooting households, razing community structures, and building new houses where none had previously existed. In some ways (though at a much smaller scale), it might have resembled the demolition of a neighborhood and relocation of the inhabitants during the construction of the interstate highway system in the 1960s.

The scale of the social unit seems to be different between the two communities, as well. During the 900s, the most recognizable architectural space at Morris 40 seems to be a single pit structure compound with about 18–22 meters of surface architecture. At Padilla Well during the same time period, the most obvious structural unit seems to have more than one pit structure and about 35–50 meters of surface architecture. I’m hesitant to ascribe too much to this distinction yet, but consider the differences between a nuclear family in a North America suburb, and the large, multi-generational families found in many parts of Asia. The obligations, responsibilities, and rights of household members are very different in these two scenarios.

Finally, there really isn’t evidence for a “Mesa Verde migration” in the late Pueblo I or early Pueblo II, at least at Padilla Well. If that were the case, we’d expect to see a rapid expansion of the population circa 875–925, habitations with a lot of masonry, rectangular pithouses, and perhaps even Mesa Verde white wares. It would look a bit like a big Gothic revival house, replete with Staffordshire bone-china appearing in the midst of a bunch of 1950s ranch-style homes full of Fiestaware. Nothing jumps out quite like that in the tenth-century Padilla Well community!

Over the course of the next few months, I will continue to hone my interpretations as I complete the analysis of the ceramic, lithic, and architectural data. This first glance at community history at Morris 40 and Padilla Well is instructive, but I intend to take an even closer look at the relationships between households within each community. What kinds of differences or similarities were there between ninth- and tenth-century households in the San Juan Basin? Might we ascertain how these communities were organized socially and politically? And if so, how did the political dynamics of different communities contribute to construction of the Chacoan pattern more generally

My hope is that this research might contextualize recent findings from Chaco Canyon itself. Regional centers like Chaco are, perhaps, best understood at the landscape level. Gaining a better sense of the Early Bonito Phase across the San Juan Basin may help identify and define Chacoan landscapes more generally, an important goal in the current era of widespread development around Chaco Canyon.

Acknowledgements

This research was funded by a National Science Foundation Dissertation Research Improvement Grant (Award # 1741893), a grant from the New Mexico Archaeological Council, the Binghamton University Provost’s Summer Fellowship, and support from PaleoWest Archaeology. Thank you to the National Park Service for allowing us to work at Padilla Well, and to the Ute Mountain Ute Tribe for permission to work at Morris 40. Additional support was provided by the Geophysics and Remote Sensing Laboratory at Binghamton University. Thanks also to Cory Breternitz and Adrian White, Hugh Robinson, Juanita Sandoval, Nichol Shurack, and Brian Halstead.

Explore the News

-

Join Today

Keep up with the latest discoveries in southwestern archaeology. Join today, and receive Archaeology Southwest Magazine, among other member benefits.