- Home

- >

- Preservation Archaeology Blog

- >

- Finding History in the Shade of Ponderosas

(July 12, 2018)—I’ve had the pleasure of being the survey director for this year’s Preservation Archaeology Field School. Survey is the systematic on-the-ground search for new archaeological sites—a critical step in the preservation of cultural properties. Our students Sam Rodarte and Constance Connolly already gave excellent summaries of the type of work we do on survey and how we identify archaeological sites on the landscape. This year, we surveyed a portion of the Gila National Forest north of Silver City, New Mexico. In this blog post, I’ll explain why we surveyed for the USDA National Forest Service and how our work revealed a diverse range of archaeological sites.

The land we surveyed was recently part of a controlled burn by the forest service. Intentionally burning a portion of the forest may seem counterintuitive, but it actually serves an important purpose. The forests of the Upper Gila are an ecosystem evolved around regular burnings set by lightning strikes and historically set by Native American peoples. Without regular burnings, the forest builds up a dangerous level of dry fuel. A hazardous level of dead fuel can lead to massive wildfires that are more difficult to control, burn more intensely, and may pose a threat to communities.

By doing controlled burns, the forest service is better able to manage timber resources and promote a healthy ecosystem. This practice also provides an opportunity for archaeologists to survey for new sites. In a freshly burned area, there is less vegetation and ground cover obscuring archaeological sites. Our field school students diligently scoured these burnt hillsides and discovered a range of previously unrecorded archaeological sites.

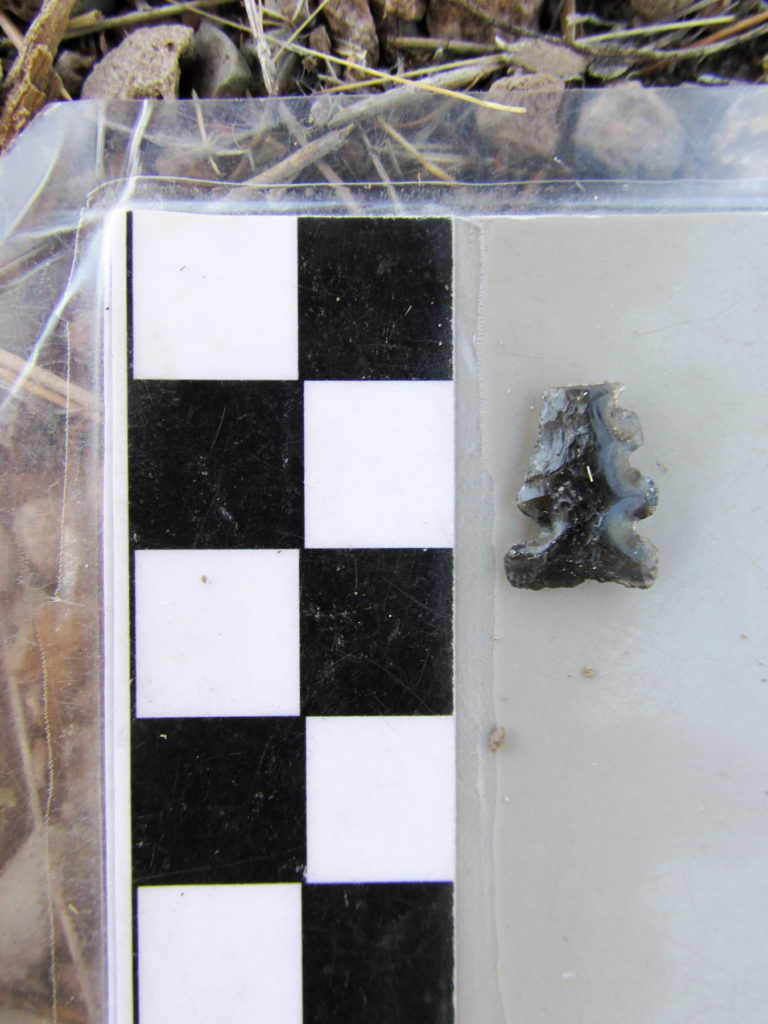

These sites convey a wide swath of the cultural history of this forest. A large lithic scatter contained an atlatl dart point likely dating to the Late Archaic period (1800 BC–AD 200). Another large lithic scatter contained a few ceramics dating from the Early Pithouse to Late Pithouse period (AD 200–950), indicating the presence of a settled community. By far the most frequent artifacts we encountered are from small Mimbres-Mogollon (AD 950–1150) habitations scattered across the land. More recent signs of human presence in the forest are refuse dumps from loggers in the 1960s. Spam cans and bottles of Bacardi might seem innocuous, but they are the latest chapter of people leaving their mark in this space. Rather than being an untouched wilderness, each artifact testifies to this being a storied cultural landscape.

Our crew will continue to survey for the remainder of the field school. I myself was a student on the 2014 field school, fresh out of undergrad and about to begin my graduate work at Binghamton University. Being able to return to the Preservation Archaeology Field School as an instructor has been an honor and an opportunity to teach and learn with a fantastic group of students and staff.