- Home

- >

- Preservation Archaeology Blog

- >

- Where’s the Buff?

(November 20, 2018)—Pottery is nearly synonymous with archaeological research in the Southwest. Archaeologists rely on it for a quick and easy means of organizing their data into spatial, temporal, and cultural categories. They also use pot sherds to chart out shifting patterns on social, economic, and religious connectivity among social groups at variable scales. The reliability of such analyses, however, depends entirely upon accurate knowledge of when and where potters were making certain types of pottery.

Archaeologists have gone through great pains to work through many of the pottery puzzles in the Southwest, so much so that we can often date archaeological sites to 50- or even 25-year intervals based entirely on the types of pottery we find on their surfaces. But those are the ideal scenarios, not always the norm. The sad fact is that in some places we have not yet been able to develop chronologies for local pottery assemblages, let alone agree upon how to do so. This is the situation we face in western Arizona and southeastern California, where indigenous potters crafted a distinctive body of ceramic vessels and objects we’ve come to know as “Lower Colorado Buffware.”

Lower Colorado Buffware was made from secondary (i.e., sedimentary) clays, and potters constructed their wares by building forms with coils of clay and then shaping and thinning them with a paddle and anvil. It is the secondary nature of the clay—meaning it was deposited relatively far from its source and has therefore been leached of many elements, principally iron—that usually renders the fired vessels with a light, sometimes buff-colored complexion. Depending on where a vessel was made, the non-plastic additives (i.e., temper) range from 0 to 35 percent of the paste composition, and include varieties of sand, crushed rock, grog, and/or shell. Often, the clay in the paste was only coarsely ground, which leaves angular clumps visible in the cross-section of vessel walls. The pottery occasionally exhibits what appears as a whitish film or slip, akin to some examples of Hohokam buffware. This effect is actually a “scum” that forms as salts in the clay are heated during the firing process. The chemical interaction is not fully understood: apparently, the salts—mobilized by water—consolidate on and slightly below the surface as water is expelled during the firing process, or they bond with iron in the clay, both of which are subsequently “burned off” during firing. This “bleaches” the vessel’s surface.

In late October of this year, I attended a workshop on Lower Colorado Buffware organized by Linda Gregonis, Jill McCormick, and Rick Martynec. The event was held at the Wellton Public Library, in the small Arizona town of Wellton, located along the lower Gila River just upstream from Yuma. The organizers settled on Wellton because it lies near the center of a vast area over which Lower Colorado Buffware is found—San Diego to Phoenix, Las Vegas to the Colorado River Delta. The workshop continued upon a discussion hatched earlier in the year at the Sonoran Symposium in Ajo, Arizona, where Rick and Linda held a session on pottery in southwestern Arizona. A shared sense of frustration over the existing Lower Colorado Buffware typology had been mounting for years, and it became apparent to the session’s participants and attendants that a meeting of the minds was in order if we were ever to move beyond the impasse.

To understand the impasse, we have to unpack Lower Colorado Buffware as an archaeological construct. The 1920s mark the first recognition of this pottery as something different from other Southwestern ceramics, and unique from the Middle Gila Buffware associated with the Hohokam tradition. Both Malcolm Rogers (with the San Diego Museum of Man) and Harold Gladwin (with Gila Pueblo) attributed the pottery of far western Arizona and southeastern California to various Yuman-speaking tribes and their ancestors. It was Harold Colton with the Museum of Northern Arizona, however, who provided the first typological definition in 1939 with his designation of Topoc Buffware.

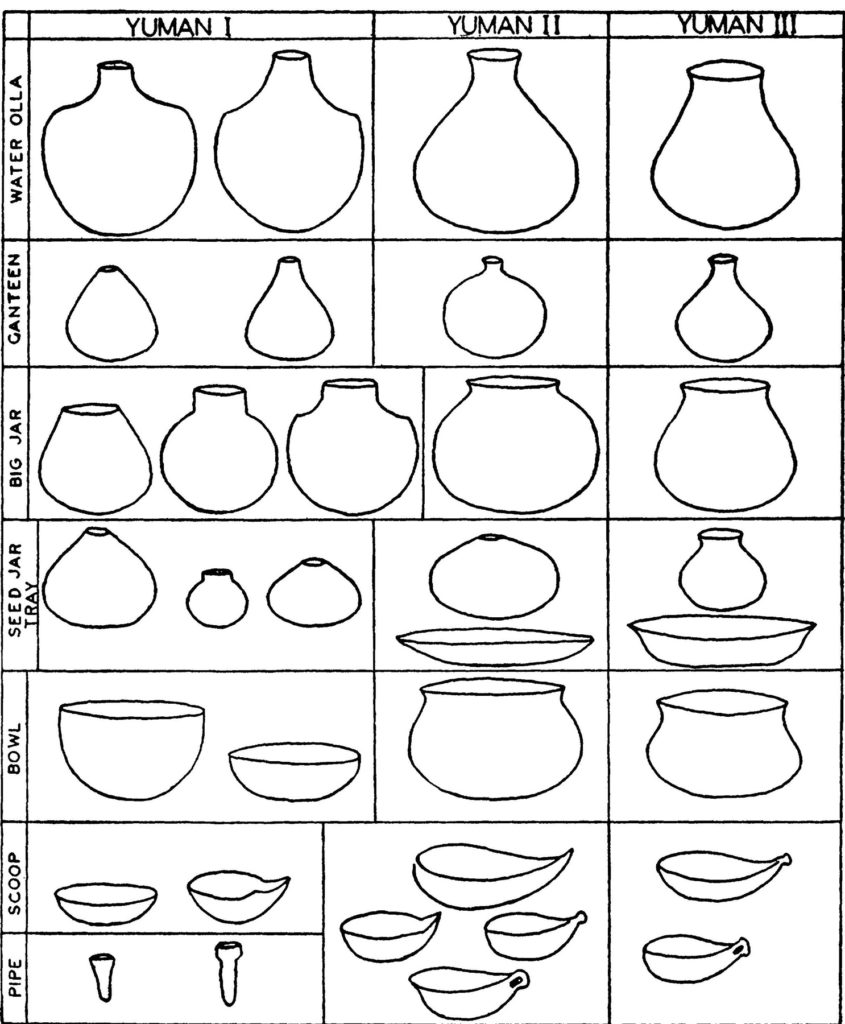

Rogers, by far the person most familiar with ceramics of the region, developed a series of provisional pottery types based on attributes of temper and paste, but he never finalized his system. He instead published in 1945 a typology based on vessel form. Although Rogers never clarified how he devised this typology, or provided any data in support of it, it is generally believed that he relied on intrusive ceramics with known date ranges, trail sequences (a type of “horizontal stratigraphy”), and the filling and recession of Lake Cahuilla (Blake Sea) to ground his typology to a temporal framework of Yuman I (AD 700–1050), II (1050–1500), and III (1500–1900).

In the 1950s, Al Schroeder, working for the National Park Service, conducted brief surveys on the lower Colorado and lower Gila Rivers. Schroeder was well-versed in Southwestern archaeology, and he adhered to Colton’s system of ceramic typology and classification. After consulting Colton about Topoc Buffware, and with Malcolm Rogers’s notes in hand, Schroeder defined Lower Colorado Buffware, to which he assigned Topoc Buff as one of 36 different types. Schroeder’s scheme organized Lower Colorado Buffware into six “series” based on temper and paste characteristics. He then divided each series into types based on aspects of surface treatment (i.e., plain, slipped, polished, stuccoed, and painted). Schroeder repurposed the names of many of Rogers’s provisional types, but the attributes differed. This has created a great degree of confusion for people working with Lower Colorado Buffware.

In the late 1970s, Michael Waters attempted to tackle the lingering uncertainty surrounding Lower Colorado Buffware. After reviewing the literature and working with Rogers’s collection at the San Diego Museum of Man, Waters essentially dismissed Schroeder’s typology. He instead published a typology that adhered closely to Rogers’s provisional types, the types that Rogers himself never finalized nor published. The chronology of Waters’s typology also followed that of Rogers, but he renamed it as Patayan I, II, and III, since at the suggestion of Harold Colton “Patayan” had eclipsed “Yuman” as the archaeological nomenclature. As with Rogers’s work, it is not clear from the written record on what basis Waters’s chronology rests, and any data to support was never presented.

By the early 1980s, there were two typologies for Lower Colorado Buffware—Schroeder’s and Waters’s. Although these typologies are not compatible, most researchers have found fault and inadequacy with both, and sometimes even intermixed them. The results of cultural resource management projects have only confounded the problem by continually challenging the chronology of Waters’s scheme, with supposedly Patayan I types repeatedly found in later contexts.

The impasse with Lower Colorado Buffware is threefold. There is the issue with incompatible typologies, which is exacerbated by the inaccuracies of the chronology accompanying the Rogers/Waters system. There is also the practical dilemma with assigning pot sherds to different types based on temper and paste attributes, not to mention that the utility of such types (because they have no apparent chronological relevance) has yet to be shown. For those of us working with these materials, the problems and uncertainties have begun to outweigh any usefulness of the existing typologies.

The workshop a few weeks ago was a step in the right direction—getting people together to hash out the challenges and to brainstorm on ways forward. The 20 participants represented an unexpectedly broad swath of researchers from Arizona and California, with multiple universities, nonprofits, contract firms, federal agencies, and tribal communities represented. There was general consensus that the existing Lower Colorado Buffware typologies are ineffective at best, difficult to apply in the field, and quite possibly counterproductive to advancing Patayan archaeology. The group split, however, when considering which attributes should be emphasized, with some still favoring temper and paste characteristics and others advocating for the significance of morphological and decorative variables.

The fundamental hurdle to refining the Lower Colorado Buffware typology has been a lack of dated contexts. Unlike in other areas of the Southwest, very few Patayan sites are stratified, and few projects have yielded material suitable for radiocarbon and archaeomagnetic dating. The projects that have provided such opportunities repeatedly demonstrate that the chronology associated with the Rogers/Waters typology is not accurate.

My research in western Arizona has brought me into the general discussion surrounding Lower Colorado Buffware. I believe western Arizona may be the ideal context for working through the many problems with Lower Colorado Buffware. For one, the lower Gila River presents a unique scenario in which Patayan and Hohokam communities resided in the same general region, and in some instances the same villages. The common co-occurrence of Lower Colorado Buffware (Patayan pottery) with better-dated Hohokam pottery types provides an opportunity to date attributes of Lower Colorado Buffware despite a dearth of stratification and radiocarbon dating. This is one of my goals for the Lower Gila Ethnographic and Archaeological Project, a collaborative research endeavor sponsored by the National Endowment for the Humanities.

My work at the Bouse Site near Parker, Arizona, is another opportunity. In fact, the Bouse Site was partially excavated in 1952 by Michael Harner because it was believed to exhibit stratified deposits containing Lower Colorado Buffware, as well as co-associations with Hohokam pottery. Although Harner never finished his analysis of the Bouse materials, since 2015 I have been reinvestigating his work at the site, and I have secured radiocarbon dates with financial assistance from Carryl B. Martin Research Award through the Arizona Archaeological and Historical Society. This project continues, as recent support from the Begole Archaeological Research Grant through the Anza-Borrego Foundation will enable me to continue my analyses of the Bouse Site materials curated at the Phoebe A. Hearst Museum of Anthropology on the campus of the University of California at Berkeley.

It is yet to be determined to what extent the Bouse Site and studies along the lower Gila River will help clarify the situation with Lower Colorado Buffware, but I am optimistic. Regardless, the history of Lower Colorado Buffware presents an interesting case in archaeological method and theory. Pottery “types” are not emic designations, in that they are not defined by the people who actually made the vessels. Ceramic typologies are archaeological constructs, meaning we develop them based on whatever attributes we choose as the relevant criteria. In essence, typology is a tool to assist archaeologists in answering questions about chronology, cultural affiliation, technology, and similar subjects. The various types of Lower Colorado Buffware—17 in the Rogers/Waters scheme, 36 in Schroeder’s, and another 12 or so in use among various researchers—have not yet proven useful for answering questions of archaeological interest. They don’t help us date archaeological sites, and so far only a handful of studies has attempted to use them to investigate patterns of exchange, interaction, and mobility. There is much, much work to be done.