- Home

- >

- Preservation Archaeology Blog

- >

- Along the Gila Watershed

(November 26, 2018)—One of our current areas of research here at Archaeology Southwest is focused on how archaeological culture areas along the Gila River were connected in the past. Our Fluid Identities research program examines how people in the past expressed social identities in varied ways along this river system.

Thinking about these connections has been a fun and interesting process for our team so far. My own research has focused largely on the upper stretches of the Gila River in New Mexico, as well as the rest of the Mimbres area stretching east through the Mimbres Valley and to the Rio Grande. When I visit archaeological sites in the Hohokam area, I often see aspects of them through the lens of their similarities and differences in comparison with Mimbres area sites during the same time periods.

Recently, I had the opportunity to visit Casa Grande Ruins National Monument on a “backcountry tour” with the Arizona Archaeological and Historical Society, which offers monthly trips to points of interest around the state. Dr. Douglas Craig, an archaeologist who has worked extensively in the area, led us to several areas of the monument normally closed to the public.

Some of the features we saw are common in Hohokam archaeological sites but not along the Upper Gila, including a type of roasting pit called an horno. These large pits were used for cooking agave and other foods; excavation data show these were mostly plant materials but occasionally meat. We don’t commonly see roasting pits in the Upper Gila area, although sites in the southernmost stretches of the Mimbres area do have them.

Another interesting stop on our special tour was an area where long-ago excavators had deposited unwanted pottery sherds. Modern excavations would have curated these in a repository, but some of the site’s first excavators operated under a set of principles different from the more preservation-minded standards we embrace today. Although I am not a pottery expert (my heart belongs to animal bones), several sherds in the pile looked like old friends. Swirly red-on-buff designs from the AD 750–850 time period look a lot like the red-on-white designs on pottery from the same time period in the Upper Gila, although elements like the clay the pots are made with and the presence or absence of a white clay slip differentiate the two pottery types.

Another kind of sherd I recognized in the pile was Roosevelt Redware, also known as Salado polychrome. This type was made in both the Upper Gila and the Hohokam areas in the 1300s, as the Salado phenomenon spread a common set of pottery and beliefs across parts of both regions. Our archaeological field school outside Cliff, New Mexico, is focused on this time period, so our team is used to seeing lots of sherds like these.

Inside the museum, exhibits focused on the Hohokam area and on notable features and artifacts from Casa Grande and its surrounding community. Here, too, several connections jumped out at me from among the display cases. A Hohokam stone bowl reminded me of the stone bowl fragments we were very excited to find at Gila River Farm two years ago. Some of the obsidian from Casa Grande comes from the Antelope Creek obsidian source near Mule Creek in the Upper Gila area. This obsidian was widely circulated in the ancient past, especially during the 1300s, when Salado social connections facilitated its movement throughout the southern Southwest.

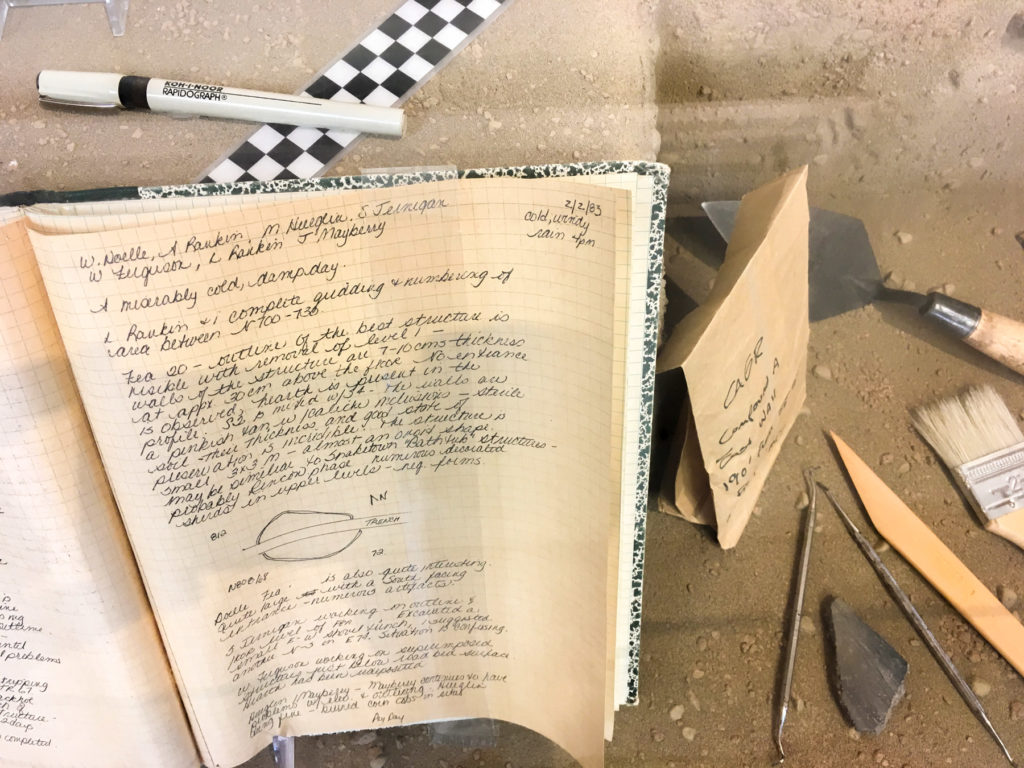

I also noticed an even more personal connection between the museum displays and Archaeology Southwest in a set of field notes on display, in which a certain W. Doelle complained of “a miserably cold, damp day.”

Interesting parallels are also visible in the most impressive features of the public areas of the monument. The ballcourt along the interpretive trail was filled with bright yellow flowers on our visit. The large-scale public architecture of Hohokam ballcourts brought people in these communities together during the centuries from AD 750 to about 1100. Large pit structures called great kivas served as community spaces starting at around the same time in the Upper Gila and elsewhere in the Mimbres area, but by AD 1000 they were replaced by open plazas within Mimbres villages. Communities in both areas felt a need for specialized architecture for designated community spaces at the same time, but the types of structures they chose for this purpose differed greatly.

In the 1300s, community architecture at Casa Grande included platform mounds and the four-story adobe great house for which the site is named. During this same time period, the Salado sites of the Upper Gila again used open plazas in the villages for community activities; no public architecture analogous to a platform mound or a great house has been found there. The adobe of the great house, however, bore some similarities to the adobe architecture I am used to seeing at a much smaller scale in house structures in the Upper Gila.

The courses or lines in which the wet adobe was laid down to form the massive great house walls bear a close resemblance to the courses of adobe visible in fourteenth-century houses in our field school excavations, and also to the reconstruction of a Salado room Allen Denoyer has been leading our students in building at our field camp. Both types of structures were made not with bricks or forms, but by piling basketfuls of wet adobe onto partially dry courses below. The adobe was packed and smoothed by hand, and then allowed to dry enough to support the next course. Although the great house is enormous in comparison, the construction sequence here produced differences in adobe color and texture very much like those we see in the Upper Gila.

The similarities I noticed on this recent trip are just a few examples of a broad pattern archaeologists see across the Southwest: material culture across large areas changes in parallel ways and at the same times during some centuries, but shows very different developments in others. Just as interesting are periods when connections don’t show clearly in the most noticeable artifacts (such as traded pottery and public architecture in the AD 1000s), but continued in ways that are harder for us to discern (as with obsidian exchange and certain pottery designs). We are still working to understand the nature of the social connections between villages on different parts of the Gila River that contributed to this synchronicity.

For more information on Casa Grande Ruins National Monument, see the monument web page (link) and check out their very active support organization, Friends of Casa Grande Ruins National Monument (link).

One thought on “Along the Gila Watershed”

Comments are closed.

Great article, thank you. There is one shard in your picture that I do not recognize. It is the reddish one with very large temper in the bottom center of the picture that almost looks like a brick in color. Do you know what that is? It looks distinct from the others. Thank you.