- Home

- >

- Preservation Archaeology Blog

- >

- Lower Gila Field Notes

(March 28, 2019)—About six months ago, at the beginning of October of last year, I began fieldwork for the Lower Gila River Ethnographic and Archaeological Project. Known as LGREAP to my crew and volunteers, this three-year endeavor aims to better understand the Patayan dimension to the lower Gila’s cultural landscape.

As I recently explained at an Archaeology Café in Phoenix (opens at YouTube), if you don’t know much about Patayan archaeology, don’t fret—you have a lot of company. With that in mind, I want to begin by clarifying that the archaeological label of Patayan derives from pataya, an Upland Yuman (Hualapai, Havasupai, PaiPai, and Yavapai) word that translates as “ancestors.” “Pataya” is therefore the noun, while “Patayan” is an adjective form.

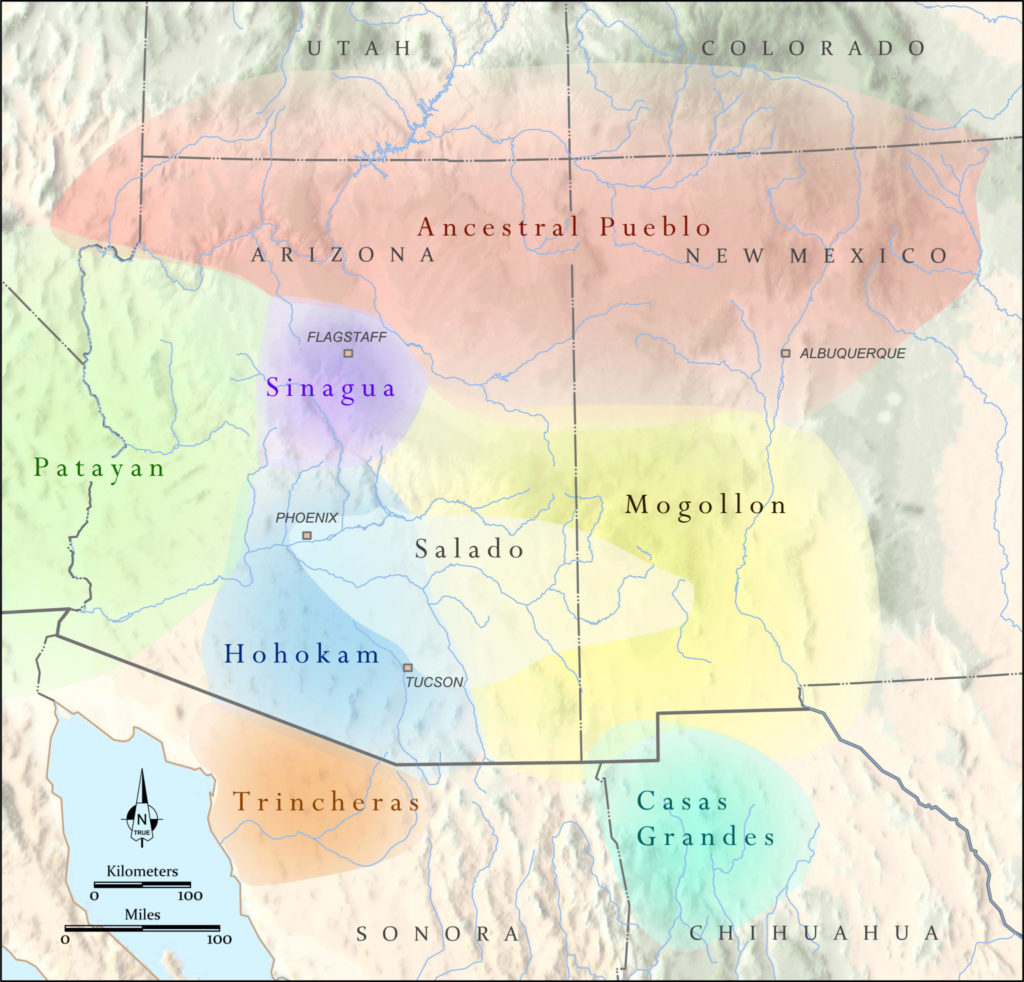

For a variety of reasons (which I intend to explain in a future post), Southwestern archaeologists have largely omitted Pataya as a topic of any serious scholarship, even though Patayan material culture is found throughout the western half of Arizona. They have seemingly relegated it to their Californian colleagues, because Patayan material culture also stretches westward to San Diego and south into Mexico’s Baja Peninsula. Unfortunately, Californian archaeologists have also tended to shy away from Patayan archaeology, partly because it seems more Southwestern than Californian. Talk about being stuck between a rock and a hard place!

In a weird way, I get the sense that Patayan archaeology has been orphaned, which is doubly odd because the founding fathers of Patayan archaeology were a cadre of Southwestern A-listers—Malcolm Rogers, Harold Gladwin, Harold Colton, and Al Schroeder essentially defined and mapped out what we at Archaeology Southwest are calling the “Patayan World.”

Culture areas, or “worlds,” of the Greater Southwest. Graphic: Catherine Gilman

And while they had lesser roles, other archaeological all-stars such as Dave Breternitz, Gwinn Vivian, Bob Euler, Paul Ezell, and Henry Dobyns added their two cents to the Patayan story. With so many heavy hitters involved, you’d think we’d have a firm understanding of Patayan archaeology, but that couldn’t be further from reality.

The last substantive publication to include a section on the subject was a book published nearly 40 years ago (Randy McGuire and Michael Schiffer’s Hohokam and Patayan, Academic Press 1982), which encouraged additional research, because the state of knowledge on the westernmost reach of the Southwest at that time was sorely wanting. The current state of affairs suggests that call to arms was not roundly met.

Patayan archaeology isn’t a total blank slate, though. Due to the founding fathers mentioned above, there is a generally accepted framework under which most of us work. Patayan archaeology is often divided into two strains: an upland expression characterized by brown-firing ceramics (Tizon Brownware) and a riverine, or lowland, manifestation recognized by buff-firing ceramics (Lower Colorado Buffware). (Read my blog post about Patayan pottery here.) “Riverine” is a bit of a misnomer, as the lowland expression includes a lacustrine variety centered on Lake Cahuilla in southern California.

At any rate, ethnography has been a major contributor to past and current understandings of Patayan archaeology because the cultural landscape of this region of the Southwest, at least as far as we know, did not witness a major social and demographic transformation on the scale of what transpired in southern Arizona (Hohokam) in the 1400s or around the Four Corners (Ancestral Pueblo) in the 1200s.

In fact, Patayan archaeology of the historic era (i.e., post-Spanish contact) looks a lot like that of the pre-contact period, which is why the span of time from 1500 to 1900 is referred to as the Patayan III period rather than the Historic period, or some other label that would essentially imply the people met by the Spaniards were somehow different or alien from the Southwest’s earlier residents.

The spatial distribution of Tizon Brownware and Lower Colorado Buffware mirrors that of the distribution of Yuman-speaking tribes described in historical records. And because the archaeology of post-1540 looks much like that of 1539 and earlier (why would it not?), most archaeologists have been comfortable using ethnography of these Yuman-speaking tribes to inform on the past. If this approach holds merit—and I believe it does—then the lifestyles of the upland Yuman tribes (Yavapai, Havasupai, and Hualapai) provide sound analogues for the upland Patayan archaeological expression.

This implies a relative low reliance on agriculture with a seasonal pattern of mobility attuned to the location and availability of resources. With regard to the lowland Patayan expression, the riverine Yuman tribes (Quechan, Cocopah, Mohave, and Piipaash) are the most appropriate models for Patayan archaeological sites located along the river margins, namely the lower Gila and lower Colorado Rivers. That being the case, the associated archaeological sites should show a higher degree of residential stability and reliance on agriculture.

Indeed, the ethnographic record indicates there were sizable communities of Yuman-speaking tribes living and farming along the lower reaches of these rivers for centuries. Rather than invest in canals, the Yuman-speaking tribes relied on floodwaters to irrigate their crops (as did most O’odham farmers during the historic period). This meant people spent much of their time in and around the floodplain, near their fields.

But where is the archaeological signature of the Southwest’s westernmost farmers? Some archaeologists familiar with this region have written off any chance of learning more about the riverine aspect of the Patayan World because of the powerful flood regimes of these rivers. It is generally assumed that because people lived and farmed on the floodplain, many of their residential areas have been washed away or buried under a serious overburden of flood sediments. Rare discoveries of deeply buried Patayan sites on the lower Colorado River floodplain provide some validation of that assumption.

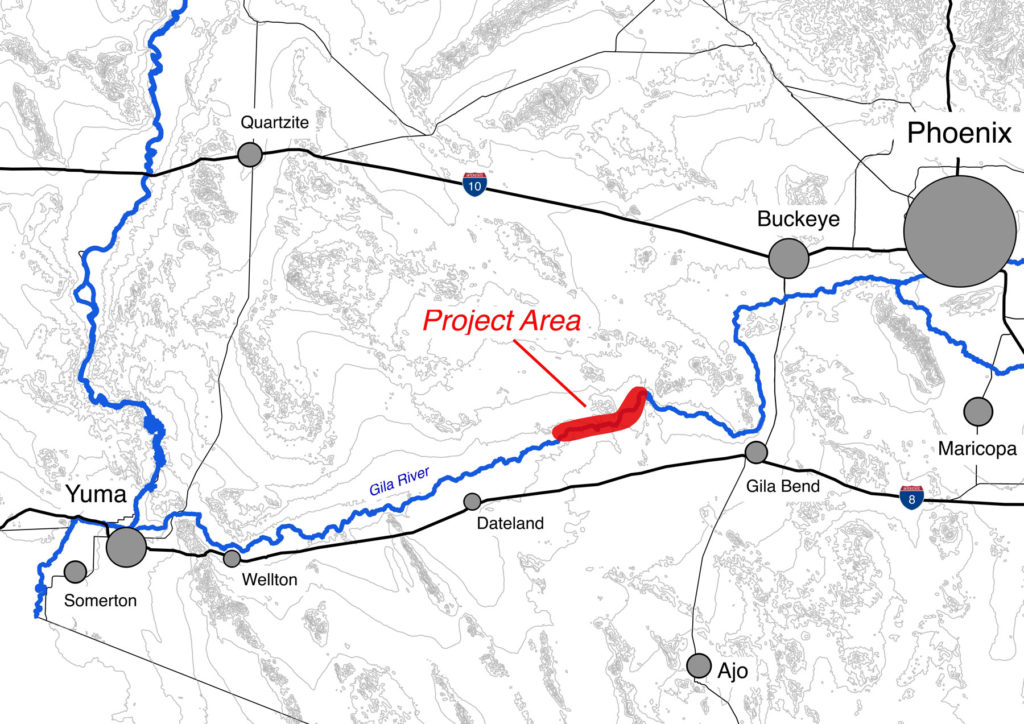

This issue with site preservation on the lower Colorado is why I believe the lower Gila River has a major role to play in Southwestern archaeology. Although known to overflow its banks on a regular basis, the flood dynamics of the lower Gila were different and less severe as that of the Colorado. This has led me to suspect that Patayan villages may still be present in certain areas. Randy McGuire had the same suspicion 40 years ago, but no one has really gone out to look—until now.

I’ve been tromping across the lower Gila for the better part of four years now, mostly in support of our Great Bend of the Gila National Monument initiative. During that time, I have stumbled across numerous places that, to me at least, look like the locations of former villages—dense scatters of broken pottery, chipped stone, and fire-cracked rock. When I checked the site records, these places were either unreported or plotted with small dots and labeled as “camps.” Strangely, some of these “camps” are as large or larger than the Hohokam village sites I’m familiar with in the vicinity of Gila Bend. Equally strange is the fact that the locations of some of these “camps” correspond with place names and descriptions of historic Piipaash villages.

So, this past fall I began a systematic inventory of these “camps,” as well as the petroglyphs and geoglyphs situated between them, located between the Painted Rock Dam and Agua Caliente. I selected this as the project area because Spanish and Mexican records indicate the lower Gila from around the town of Buckeye to Agua Caliente was home to a large population of Piipaash from at least 1695 to about 1830, which I detailed in an ethnographic overview of this region (opens as a PDF). I chose to focus on the reach below the dam because it had avoided being inundated by the Painted Rock Reservoir and is the area least impacted by modern agriculture.

I started by walking the silty banks of the now-dry river, and I quickly learned that residential sites lie in practically every place where the river’s first terrace is intact and unplowed. Although fieldwork has just begun, a Patayan settlement pattern is slowly emerging from this research. In ways, it mirrors what I had expected based on historic descriptions of Piipaash, Quechan, and Mohave settlements—dispersed rancherías along the margins of floodplains.

There are some notable differences, however. Some sites are much larger and exhibit denser concentrations of artifacts. It is not yet clear if these were actually larger residential areas (more akin to villages than rancherías), or places that were inhabited for longer periods of time, or both.

Although I don’t yet have answers to these questions, I have learned through this project that it is actually quite challenging to do research on a topic that has been ignored and overlooked for so long. This is not because it is uninteresting, but because there isn’t a strong body of prior work and case studies to build upon. But I am up for the challenge, and I look forward to sharing updates on LGREAP as we trudge on.

This three-year study was awarded a Collaborative Research Grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities (RZ-255760). The NEH is an independent federal agency created in 1965. It is one of the largest funders of humanities programs in the United States and awards grants to top-rated proposals examined by panels of independent, external reviewers. Any views, findings, conclusions, or recommendations expressed in this study do not necessarily represent those of the National Endowment for the Humanities.