- Home

- >

- Preservation Archaeology Blog

- >

- The Women’s Park, continued

Today we continue with the conclusion of Burrillo’s essay on the women who worked to protect Mesa Verde. Read part one here. Happy Women’s History Month!

(March 30, 2019)

Differing Visions and New Legislation

The feud between Virginia and Lucy came to a boil rather quickly, with the latter allegedly referring to the former as “Mrs. Flora McFlimse McStingee” in notes compiled by archaeologist James Snead, and with Virginia publishing vicious missives in Colorado newspapers about Lucy’s alleged attempts to “bury” the Colorado Cliff Dwellings Association in the “grave of a national park.” Parallels with modern public lands debates hardly need mentioning. Peabody eventually split from the Association, taking a number of disgruntled members with her, and made a tactical move that effectively unseated McClurg.

Rather than remaining in Colorado trying to drum up local support, Lucy made tracks to Washington, DC, and stepped smoothly into the role of official spokeswoman for the proposed Mesa Verde National Park. There she teamed up with Hewett, who was busy drafting the Antiquities Act for the dual purpose of creating the first piece of federal legislation that called for protection of archaeological sites and booting Richard Wetherill out of Chaco for violating it.

The year was 1906, and it would be a momentous one. Teddy Roosevelt signed the Antiquities Act into law, adhering largely to the original form written by Hewett and Congressman John Lacey and including the provision that presidents may create—but not shrink or rescind—national monuments in order to protect landmarks, structures, and objects of historic or scientific interest.

Given the authority the Antiquities Act confers in terms of protecting pieces of the landscape, and that it was written by an archaeologist and has the word “antiquities” right there in the title, a lot of people think the creation of Mesa Verde National Park that very same year was a result. Oddly enough, it wasn’t. Two congressional bills—the Hogg Bill of June 7, 1906, and the Brooks-Leupp Amendment of June 29—actually created the park, with Roosevelt signing the amended bill into law afterward. Roosevelt was probably waiting patiently for this to happen rather than jumping the gun and turning it into a national monument.

A Strange Twist

What followed is probably the strangest twist in the story of The Women’s Park. Although we do not know whether Virginia and Lucy ever reconciled, we do know that Virginia tried to have her husband installed as Mesa Verde’s first superintendent—despite the fact that she’d damned the thing before its birth! When that effort failed, she moved to align the Colorado Cliff Dwellers Association with “Professor” Harold Ashenhurst, whose stated goal was to relocate a cliff dwelling from the Mesa Verde area to Manitou Springs where tourists could enjoy it.

To that end, more than a million pounds of rock was brought by automobile—there was no train—from a site near McElmo Canyon and reconstructed in Manitou Springs using local wood and cement (yes, cement). Lucy wrote a letter to Hewett in which she lamented what seemed to her like a grievous act on the part of her former rival: “I regret exceedingly that this miserable business could not have been stopped.” Hewett was to have his own role in this debacle, however.

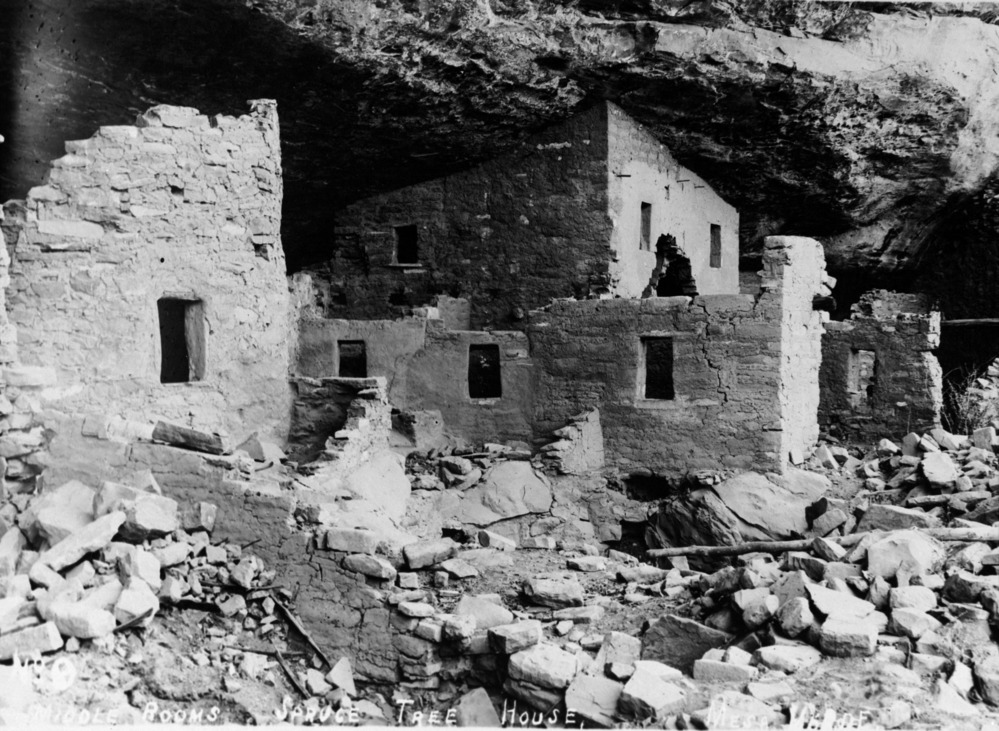

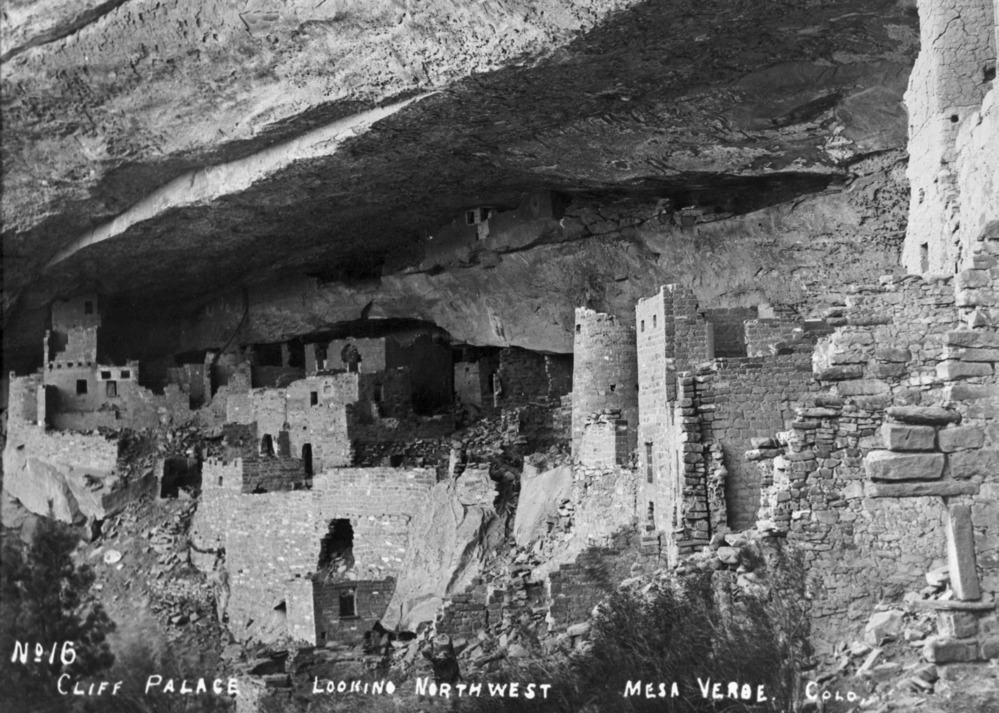

Today the website for the place notes that Virginia McClurg hired the Manitou Cliff Dwellings Ruins Company to move the structures from southwest Colorado “to preserve and protect these dwellings from looters and relic-seekers.” Not so fast, though: the Manitou Springs structures are modeled after Spruce Tree House, Cliff Palace, and Balcony House. The McElmo Canyon dwellings they are purported to be would not have looked anything like what they do now.

In fact, the rocks used to build the “cliff dwellings” at Manitou Springs probably didn’t come from a cliff dwelling at all. Local historian Fred Blackburn thinks they came from a tumbled-down pueblo located in an open field on private land. Although nobody knows for sure, we do know that if something like the enormous three-story structure complex in Manitou Springs had been plucked out of an alcove in McElmo Canyon, it would have left a considerable gap behind—of which there is a suspicious lack.

Furthermore, Ashenhurst was hardly a professor, as claimed. He was a Texas entrepreneur who wanted to build a model cliff dwelling nearer to the urban centers of the Front Range in order to cash in on the cliff-dweller craze. This aspect of the Manitou Springs Cliff Dwelling project didn’t go unnoticed by the Colorado Cliff Dwellers Association, and 40 women resigned from the Association in disgust. Ashenhurst was derided as a “medicine show operator” and worse, and he would eventually embark on a campaign to convince the public that the Manitou Springs dwellings were authentic.

Meanwhile, Virginia’s own efforts—although woefully misguided—weren’t so prosaic or greedy. She thought she was doing something positive by relocating (or, more likely, entirely fabricating) cliff dwellings from southwestern Colorado to an area that was well-situated for tourism, and intended that they serve not to fool people but to educate them.

Here is where Hewett re-enters the tale. As arbiter of all things Southwest archaeology at the time, he expressed nothing but disdain for the effort, at least according to historians such as Joseph Weixelman and Andrew Gulliford. And yet, he also served as consultant in its construction, and there is plentiful evidence to suggest that he gave the site his official approval. We may only speculate about why he did so, given Hewett’s irascible nature and fierce criticism of all nonscientific archaeological shenanigans, but it probably had to do with McClurg’s more candid and public modus operandi. It was an ugly effort, but it was conducted with a well-intended (however questionable) motive.

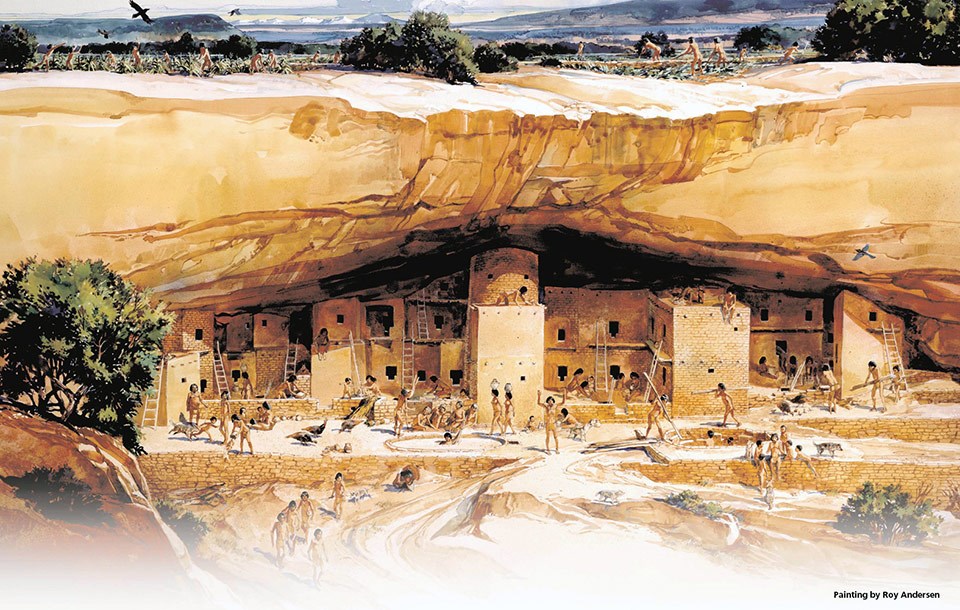

Visiting Mesa Verde required a ride of several days, the last of it on foot or horseback. Most people of that era couldn’t afford—or simply weren’t interested in—making such a grueling journey to see ancient architecture. And yet, as scientists are becoming increasingly keenly aware in these turbulent times, public support is crucial to protecting public places. Thus, as discomforting as it may be, access and preservation must coexist; humility and sacrifice are sometimes required to keep the people on your side, and that includes doing things like stabilizing or outright constructing “visitor-ready resources” in places where visitors can actually get to them. The balancing-act management strategies of places like Mesa Verde, Wupatki, Chaco, and Bears Ears are, in large part, endlessly looping reiterations of this lesson.

Legacies

The Colorado Cliff Dwellers Association eventually disbanded and became affiliated with the Archaeological Institute of America. Virginia McClurg died in 1931, and Lucy Peabody followed in 1934. The closest either woman ever came to a commemorative presence in the park was in 1921, when superintendent Jesse Nusbaum was sent a white marble marker signifying McClurg’s and the Association’s contributions. The rest of the women still involved in the Association caught wind of this and demanded that other leaders deserved equal recognition, compelling Nusbaum to ship the thing back to McClurg in Colorado Springs.

Things didn’t stay positive between the National Park Service and the Utes forever, either. Subsequent episodes have included the former extending the park boundary without the latter’s permission and the latter then taking advantage of a surveying error by the former to commandeer a popular road into the park—all of which happened well after Lucy and Virginia’s time.

Meanwhile, back in 1907, Hewett had sought to honor Lucy Peabody by renaming Square Tower House to Peabody House. This worked for a few years, until it was struck down by the Department of the Interior amid a chorus of protests. That effort was also revived in 1921, and struck down again.

Today, most visitors to Mesa Verde have no idea why it’s nicknamed The Women’s Park, and in fact most aren’t even aware that it is. But Lucy and Virginia’s torch is still carried by groups like Great Old Broads for Wilderness, a coalition comprised of “feisty lady hikers” formed in—fittingly enough—Durango in 1989 to refute a Utah senator’s disingenuous contention that wilderness areas needed roads “for the aged and infirm.”

And, of course, we have the park itself as a testament to their efforts—as well as that bizarre thing in Manitou Springs. Still, as our culture increasingly urges recognition of women’s contributions and struggles, I think it’s about time for Lucy and Virginia to get that commemorative plaque at Mesa Verde.