- Home

- >

- Preservation Archaeology Blog

- >

- A Perspective on the Lower Gila River Ethnographic...

(April 22, 2019)—Before I begin, I feel it’s important to provide context for the reader as to who I am. My name is Skylar Begay and I’m 25 years old. I was born on the Navajo Reservation in Fort Defiance, Arizona. I have lived in various places on the reservation, but I call Flagstaff, Arizona, home. I have worked for the Arizona Conservation Corps (AZCC) every summer since I was 17 in one capacity or another. When I wasn’t working for AZCC, I was attending Arizona State University, where I studied Geography and Sustainability. Most recently I joined the Forest Service (USFS), working in Colorado’s Ouray Ranger District building and maintaining trails.

I began work on the Lower Gila River Ethnographic and Archaeological Project (LGREAP) with Dr. Aaron Wright on February 6, 2019, as part of the Arizona Conservation Corps’ Individual Placement program. This day would mark the first of my experience as part of an archaeological project. Prior to this, I had led AZCC crews all over Arizona, from Saguaro National Park all the way up to Grand Canyon National Park. In that time, my crew and I had done some work for Grand Canyon National Park’s Tusayan Ruins to protect and preserve a kiva and other architectural remnants there. Aside from that small project, I had little to no experience in anything archaeological. Growing up in the Southwest, however, it is difficult not to be exposed to places like Mesa Verde in Colorado, Canyon de Chelly on the reservation, or places around my hometown such as Walnut Canyon and Wupatki National Monument. In short, I knew of archaeological sites around the Southwest and had visited many, but I knew next to nothing about the science of archaeology when I arrived that first morning.

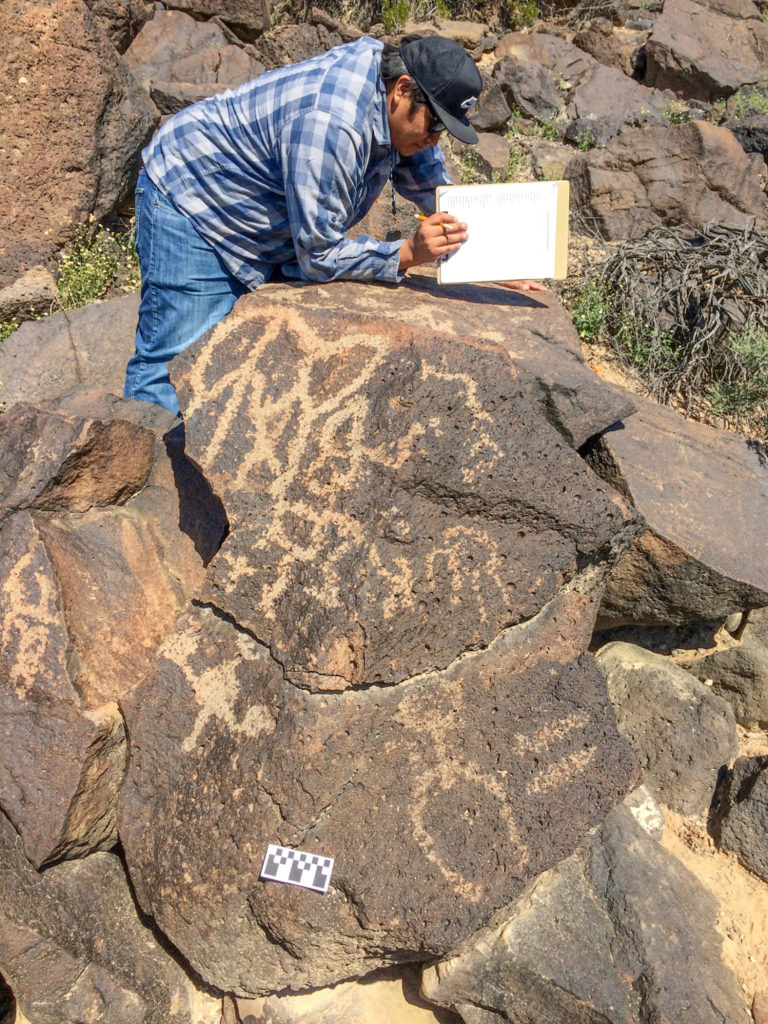

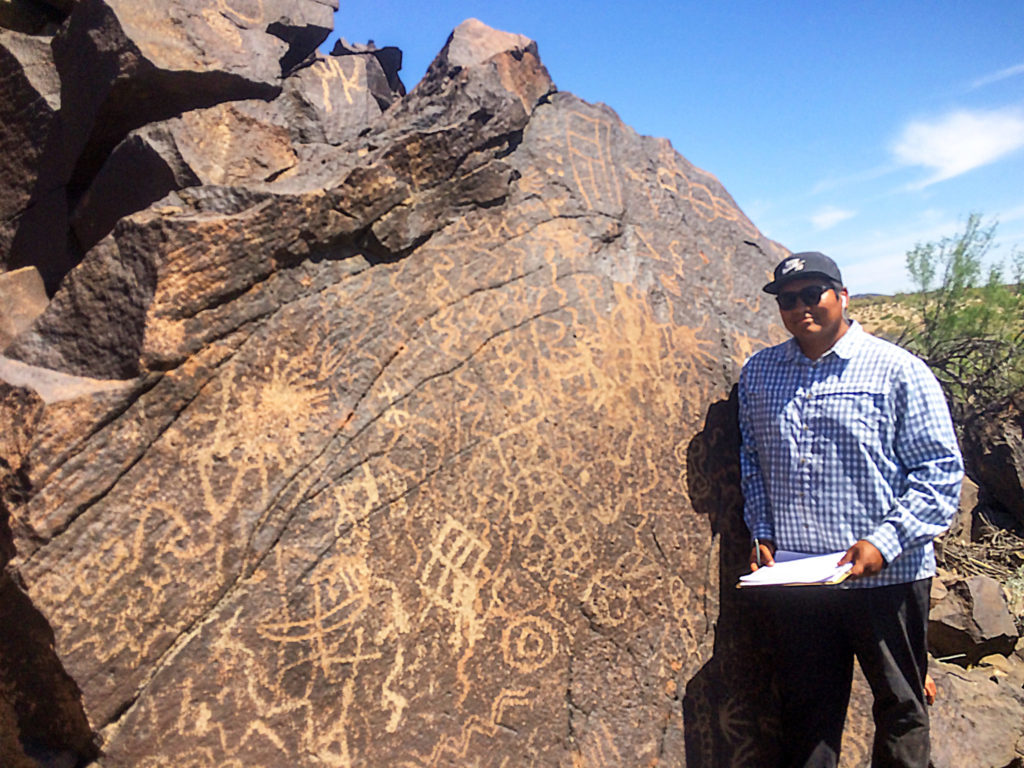

Thankfully, I quickly learned that although the work was new and different from much of my past experience, it was not beyond my ability; as each day passed, I began to get the hang of things. I was fascinated by the technical aspects of thoroughly documenting the sites we came upon. Slowly but surely, as my confidence grew, I began documenting more complex and intricate petroglyph panels. The forms themselves, which intimidated me at first, became familiar as I memorized the various codes used to describe the condition and types of glyphs. I became adept at discerning a “blob” glyph, as we called them, from a natural scrape or bash. When we broke out the drone to photograph geoglyphs from the air, it was entirely unexpected but interesting to see the adaptation of a new tool in the field.

Aside from the documentation process, the sheer volume and quality of sites and artifacts was astounding. I remember thinking to myself, “All those times you drove past this place to get to San Diego and thought it was only a desert.” After that first week in the field, I began to gain context and attach meaning to our daily excursions and activities. Each night, the team sat fireside and spoke about the day, about the next day’s plans, and about the region’s ancient and more recent history. As the days became routine and I got more familiar with the documentation process, I began to see the bigger picture the project encapsulated. I had always loved the Sonoran Desert for its rugged natural beauty and now I was learning of the Peoples who had once called it home and whose descendants still do. I realized the landscape had another layer of beauty I had not been aware of, one that was just as mysterious and captivating.

One aspect of the bigger picture that became apparent was the need for preservation of cultural resources spread across natural landscapes. I realized the land influenced the formation of a People, that those people left their own imprint on the land, and that this landscape could not be fully appreciated without taking both into account. As we walked the landscape surveying and mapping a crisscrossing network of trails, photographing geoglyphs, analyzing sherds by the hundreds, and sketching 20-foot-tall petroglyph panels, I began to form a connection to the land and those who had come before me. Although I am Diné (Navajo), I do not feel that this connection would be or should be felt only by an indigenous person; rather, I felt it was a universal human connection that would be appreciated by anyone who chose to embrace it. In this way I came to see how places like the Lower Gila are crucial in connecting with the deep, rich history of the Peoples who came before.

On the flip side, I also saw how more accessible and well-known sites such as Painted Rock Petroglyph Site have been damaged due to large numbers of visitors who were not aware of site etiquette. One advantage the Lower Gila has is that a number of its sites are not easily accessible or well known, and those who do know of it tend to be those who know how to enjoy a site without damaging it. With that in mind, I realized that while protection of the Lower Gila (or any cultural resource) is important, the way it is protected is equally important. An official designation as a National Monument or National Conservation Area may end up being detrimental to sensitive cultural resources if great care is not taken in its implementation. It is also important that local Tribal Nations be included in that conversation: their ancestors inhabited the region, and they have the most direct connection to it.

All told, my time spent working on the LGREAP has been illuminating in many ways. I learned about the Sonoran Desert as an ecosystem, and about the Patayan and Piipaash people who lived here. I learned of a rich cultural landscape densely packed with artifacts and sites, and how to document them thoroughly. After all, you can’t protect what you are not aware of. I learned the intrinsic value cultural sites like the Lower Gila have for contemporary people (Indigenous or not) and that it would be a tragic loss were it not protected in the correct manner for current and future generations to learn from. Lastly, I learned appreciation for a place many would discount as barren desert as I had once, but whose deep history and beauty reveals itself layer by layer to those willing to look.

This three-year study was awarded a Collaborative Research Grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities (RZ-255760). The NEH is an independent federal agency created in 1965. It is one of the largest funders of humanities programs in the United States and awards grants to top-rated proposals examined by panels of independent, external reviewers. Any views, findings, conclusions, or recommendations expressed in this study do not necessarily represent those of the National Endowment for the Humanities.