- Home

- >

- Preservation Archaeology Blog

- >

- Clues from Experimental Archaeology

(August 1, 2019)—Now that we’ve wrapped up another field season of the Upper Gila Preservation Archaeology Field School, I thought I’d take a minute to talk about what we learned at the Gila River Farm site this season. I especially want to share how the Experimental Archaeology portion of the program from years past helped us figure out part of the site structure this year.

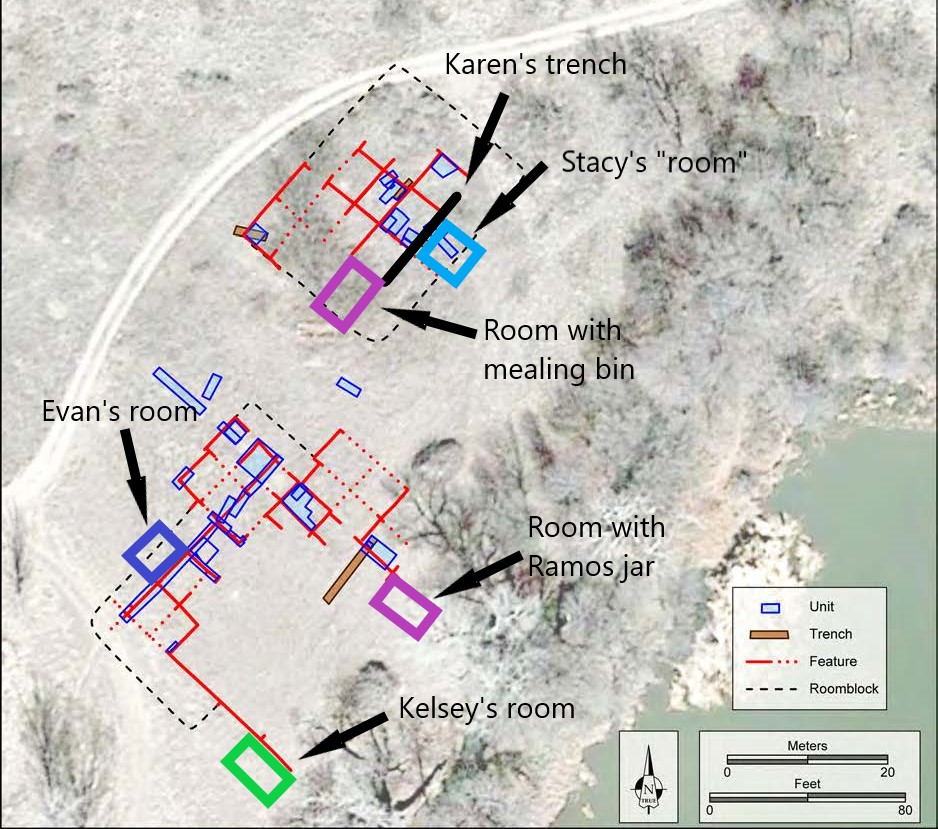

This year, we opened up parts of three rooms in the southern room block. Our main goals were to define the eastern edge and to get samples from rooms in the southern portion of the room block. With that in mind, Evan and his crew excavated a portion of a room on the southwest side, Kelsey and her crew excavated a room on the southeast side, and my crew excavated a room on the northeast side.

Each room was interesting in its own way. Evan’s room had a very nice floor and the second complete hearth we’ve found at the site. It also had pieces from five perforated plates—objects that point toward Kayenta heritage. Kelsey’s room had a hearth that had been disturbed by a historical period trash pit and the first-ever (that I know of) granary found in the Upper Gila! My room had about 75 percent of a Ramos Polychrome jar, which would have come from the northern Chihuahua region.

As it turned out though, none of them had the information we were looking for. In the last few days of the field season, we found out by digging wall trenches—shallow trenches following the tops of the adobe walls—that there are rooms east of those that Kelsey and I excavated and, quite possibly, one to the west of Evan’s room.

In the northern room block, my crew opened up a small part of another room. Like other rooms in that room block, which had been excavated in the 2016 and 2018 field seasons, this one had a grinding station (mealing bin) against the southern wall of the room. These features consist of bowls set into the room’s floor in conjunction with manos and metates on the floor nearby, sometimes set in place with adobe. People would have used the ground stone to grind corn or mesquite pods and then swept the contents into the bowl in the floor. This type of feature at a Salado site points toward Mogollon heritage.

While we were busy excavating our rooms, Karen kept herself busy digging wall trenches. For the past several years, we have been curious about the east side of the northern room block, and we thought that maybe it had been disturbed by heavy equipment related to farming activities. A couple of years ago, Stacy excavated a room that didn’t have a great floor, and we were never really sure about its north wall. It had postholes, though, and the west wall of the room was definitely there, but it was a lot nicer on its east face than its west face. We decided to take another look at it, and Karen single-handedly dug out the entire wall in a 13.5-meter-long trench! (That’s almost 45 feet long.)

The wall was just as we remembered it; really nice on its west face and really eroded on its east face. Just as we were trying to figure out why that might be, we got the opportunity to go and visit the structure that Allen and our 2014–2015 field school students built in Mule Creek.

The structure had been standing there, untouched, for the past four years without any remodeling or work to preserve the walls or roof. It was in surprisingly good condition for the most part—the mud on the roof had mostly eroded away, but the interior walls were in fairly good shape and the roof beams and support posts were intact.

When we looked at the exterior walls, however, they were eroding at the ground surface just at the level of the cimientos (stone wall footings). The way that the walls were being undercut right at that level was strikingly similar to the way that the east-facing walls in Karen’s trench at the Gila River Farm site had eroded. In fact, the interior walls of the Mule Creek structure were in nearly perfect shape, much like the ones at Gila River Farm, some of which even had wall plaster on them.

It was at this point that we realized that Karen’s wall at Gila River Farm was most probably the eastern exterior wall of the room block, and the east side wasn’t disturbed by heavy equipment (yay!). The “room” that Stacy and her crew dug in a previous season was likely an outside work area that had a ramada to provide shade, which would account for the postholes and poorly preserved surface.

Every year, the Experimental Archaeology portion of the field school helps the students and staff really understand how the things we see in the archaeological record got there. When our crews were building the structure at Mule Creek, it helped us figure out how the walls at the site were put together and why they looked like they were made of courses of adobe bricks, even though we know people in the ancient Southwest didn’t make mud bricks. Basket-loads of adobe were placed on an in-progress wall and then shaped to fit the wall dimensions, which ends up drying similar to adobe bricks. This year, the Experimental Archaeology program from past years helped us interpret taphonomic processes at the site after people were no longer living there.