- Home

- >

- Preservation Archaeology Blog

- >

- Life of the Gila

In this new series of essays at the Preservation Archaeology blog, we will highlight the deep history of the Gila River Watershed, focusing on how archaeology and knowledge shared by Tribal citizens come together to tell a story of continuity and change that began millennia ago and continues to the present.

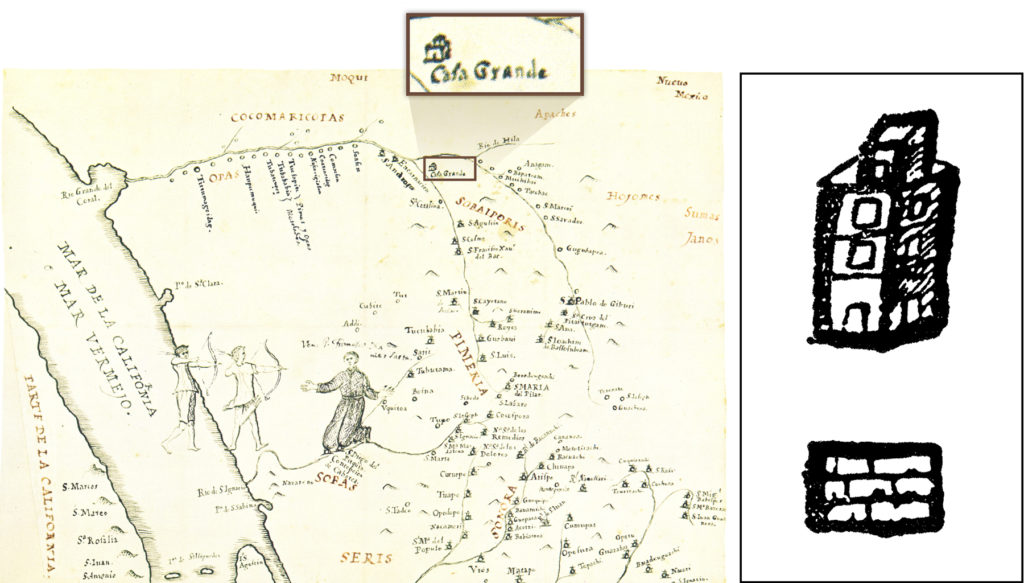

(February 7, 2020)—Home to nearly six million people, tamed by dams, and pumped such that stretches of its watercourses are usually dry, the Gila River Watershed was not always this way. The river and its tributaries were once lifelines and travel corridors for diverse peoples of the southern Southwest.

This is why we at Archaeology Southwest decided to approach the Gila at the scale of the entire watershed in our latest holistic research program—to better grasp the interconnectedness as well as the boundedness of peoples’ lives there in the past. This dichotomy of isolation and connectivity has influenced more than 13,000 years of human history in this basin.

This sense of connectedness is even at the heart of my own archaeological career, which has been guided by the Gila River since the 1970s. Project after project, whether chosen by me or assigned to me, has involved the Gila Watershed. In the process, I’ve seen places ranging from urban to remote, mundane to spectacular. My appreciation of the stories embedded in the land has expanded manyfold, and yet I am still learning to see the subtle traces of the past that are on and in the land.

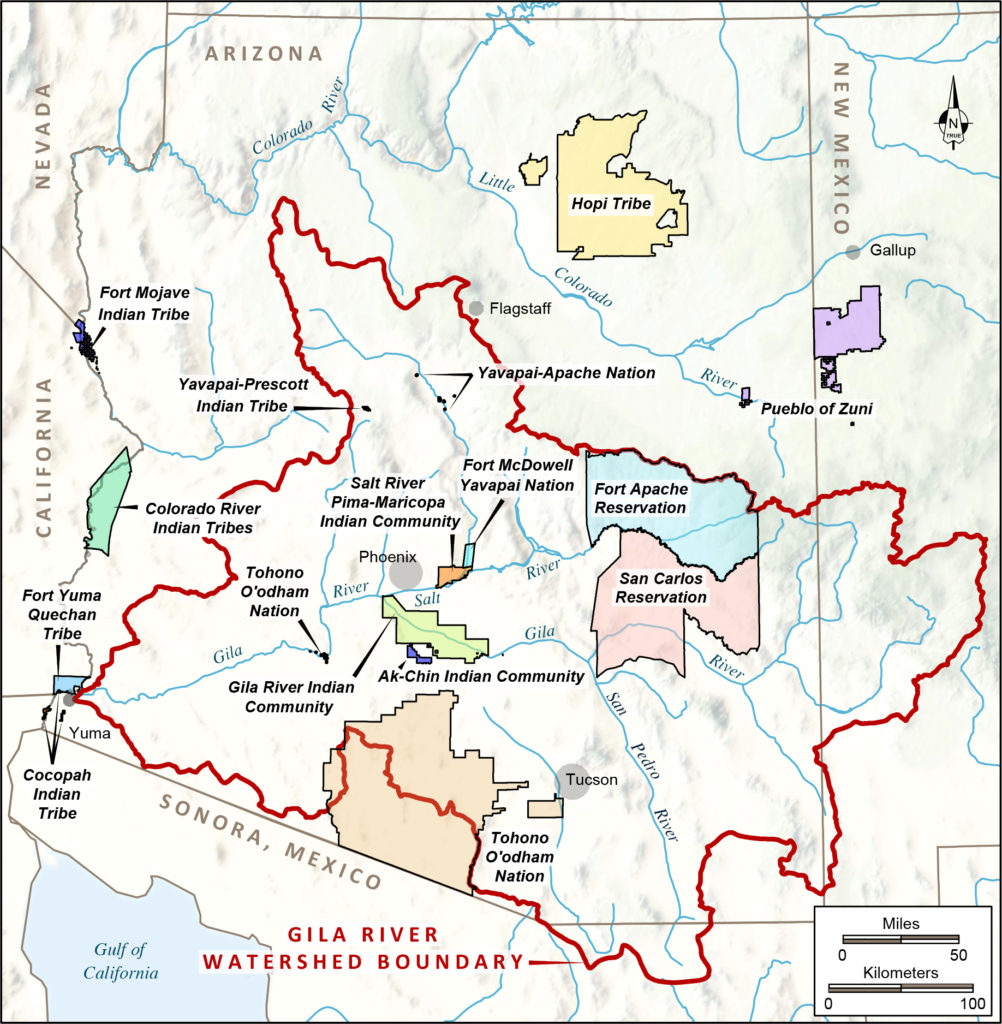

Understanding ancient changes is a great challenge, but one that those of us with an interest in the Gila’s cultural landscapes keep pursuing. Through the combined efforts of researchers, Native Americans, residents, and visitors, we continually learn more about the watershed’s diverse, rich, complicated histories. This is particularly true for understanding connections—there’s that word again—among groups of the distant past and today’s Native peoples with heritage ties to the Gila River Watershed.

The private lands and the vast public lands of the watershed have been carved away from the ancestral territories of today’s Native peoples. Access to and ownership of those traditional lands drive the economic engine that supports the nearly six million residents of this region.

In this series of essays at the Preservation Archaeology blog, we will highlight the deep history of this region, focusing on how archaeology and knowledge shared by Tribal citizens come together to tell a story of continuity and change that began millennia ago and continues to the present.

Come along with us on this journey. See how these landscapes preserve and reveal the stories of the past even through the most fragile traces. Your respect for these landscapes and sense of appreciation and responsibility toward them will also grow—manyfold.

The Gila River Watershed

The Gila Watershed extends across much of the southern U.S. Southwest, encompassing more than 58,000 square miles. Simplistically, what defines a watershed? Three things help us understand the basics of a watershed: elevation, gravity, and a drop of water. The boundary of a watershed is an imaginary line where something very real happens. That line is defined by a drop in elevation to either side of it, so that if a drop of water falls and lands to one side or the other of that line, gravity will keep it on that side and will nudge it downslope toward ever-lower elevations. We summarize it in the simple truism—water flows downhill.

Fortunately, rainfall usually consists of very large numbers of raindrops. And as they land on one side or the other of a watershed boundary, they accumulate into larger and larger rivulets that ultimately flow or seep downslope to create the rivers that are so important to human survival. In the deserts of the Southwest, watersheds are a very useful tool for thinking about how people have adapted to the challenges of making a life in an arid land.

Is there any evidence that people in the past thought about the lands where they lived as a watershed? Although we can’t be certain, a Tohono O’odham place name suggests that people understood the concept. There is a small community named Sikul Himatk toward the western edge of the Tohono O’odham Nation. That name translates to “water going around.” And if you look on a modern watershed map, the community falls right on a watershed boundary. Given that the Tohono O’odham made a successful living as farmers who ensured the survival of their crops by managing the ephemeral surface flows of desert washes, it isn’t surprising that they would perceive the significance of a place on the landscape where the water “decided” to flow in one direction or the other.

The Gila Watershed comprises diverse environmental zones, from pine forests and juniper-dotted meadows near its headwaters in western New Mexico, to the semiarid Sonoran Basin and Range along its midsection, which becomes ever-more-arid until its confluence with the Colorado River at the Arizona–California border. Much of this diversity is due to changing elevation: over its course, the Gila River drops 5,400 feet, a descent much greater than that of the mighty Mississippi.

A Landscape Extensive and Diverse

If, on a noon day in July, I were standing atop Mount Baldy—with the requisite permission of the White Mountain Apache Tribe—at the high point of the watershed, and you were standing on the riverbank at Yuma where the Gila joins the lower Colorado River, you would likely experience a temperature of at least 110 degrees Fahrenheit, while I might feel chilled by a mere breeze in the 63-degree temperature. That 47-degree difference underscores the strong relationship between temperature and elevation throughout the Gila Watershed. Precipitation also tightly correlates with elevation, as Mount Baldy has annual precipitation of more than 31 inches, whereas Yuma just barely averages 3 inches.

Biologists express the ways that elevation structures the overall environment with the concept of life zones. This simple graphic illustrates how different plant associations are expected at different elevations. The sloping lines reflect the fact that the north side of a prominence does not receive the direct sun to the same extent as the south side. As a result, temperatures are cooler on the north, which causes similar vegetation to occur at lower elevations on the north.

In general, the Gila River flows just a bit south of due west across the breadth of its watershed. For roughly half of its course, the Gila is actually two major rivers—the Salt on the north and the Gila on the south. The Salt River takes in many tributaries from the north that drain higher elevations, whereas the Gila takes in north-flowing tributaries whose headwaters are at relatively low elevations. As a result, upstream of the Salt–Gila junction just southwest of downtown Phoenix, the Salt is by far the mightier of the two major rivers. Largely tamed today by a series of dams, its once-high flows were due to melting of snowpack in the mountains in the spring each year. The Gila upstream from Phoenix took in a smaller input from snowmelt; its peak flow was due to the runoff from summer monsoon rains.

The water carried by these rivers, the topography and soils of the lands along their banks, and the people’s ability to invest their knowledge and labor in agriculture have long played an integral role in how people lived within the Gila Watershed. The particular abundance of water and farmland made the Phoenix Basin (the lower Salt River area of modern Phoenix and the stretch of the Gila from Florence, Arizona, to the Salt–Gila junction) the area of greatest population density in what we now call the southern Southwest more than a thousand years ago. This is also a major factor behind the massive population of greater Phoenix today.

Peoples of the Watershed

The Gila Watershed has never been the homeland of a single people. In this series of blogs, we consider how the peoples of the watershed changed their perceptions of who they were as peoples or cultures. How did they view their identity, and how did past identities change over time? Identity was very important in the past—as it is today. It affected how people viewed their neighbors. It affected whether they traded with their neighbors, whether they allowed neighboring groups onto their territory, or whether they treated outsiders with peaceful or hostile responses.

Farming was the main way of making a living over most of the Gila Watershed for the past 4,000 years. Farmers have been digging canals to bring water to their fields in the deserts of the Gila Basin for at least 3,500 years. Groups fine-tuned their agricultural practices to fit distinct local environments in the diverse valleys across the watershed. The wild plant and animal foods available to them also varied by type and abundance within each valley.

Supported by intensive irrigation agriculture, populations in the Gila Basin grew at a relatively constant rate after 500 CE. By the 1300s, population density was quite high. In fact, our reconstructions show that almost two-thirds of the Southwest’s population at 1300 was living in the south. The largest populations resided in the Phoenix, Safford, and Tucson Basins, but significant populations lived along the lower Gila and lower Colorado Rivers to the west and in the Mimbres and upper Gila River valleys to the east.

Identity

Although local knowledge was imperative to survival, the communities that developed in these settings were not wholly self-sufficient. Trade with groups in other valleys provided significant resources, such as salt; quality stone for making tools; and items of economic or ritual importance, including painted pottery, shell and stone jewelry, and vibrant minerals. In times of local shortage, strong ties with neighbors could ensure sufficient food.

Kinship is a basic means by which human groups decide whom to cooperate with. But as population sizes increase and distances between groups increase, people develop cultural means to define what they have in common. Often people living across a vast area still share a common set of beliefs about the world that they experience through daily, seasonal, and annual cycles. These ideas are regularly expressed in stories—stories of a group’s origins, of the roles of things as diverse as plants, animals, rocks, and rivers.

Sharing these ways of understanding the world helps forge a common identity. We see this as an essential means by which local areas—say individual valleys—maintained effective interactions among the multiple communities that needed to interact for survival.

At times, much larger-scale identities emerged, and these spanned much larger geographic areas. It is the ebb and flow of these large-scale identities that we will detail in this series. We seek to explore the “extra” aspects of regional lifeways that helped these large, inclusive identities to thrive, and ultimately to wane or be superseded by new identities.

Visiting the Past

A goal of this blog series is to boost our readers’ awareness of the rich heritage of the southern Southwest. Although reading and learning are parts of the process, we also hope to encourage you to directly experience places of the past. We are fortunate to have extensive areas of public lands across the Gila Watershed. This series acknowledges, with gratitude, that our public lands are the traditional territories of multiple living tribal nations. We want to encourage respect for these lands, which are open to all for purposes of recreation, hunting, gathering, exploring, learning, celebrating, and healing, and we will close our series with a post about the public lands of the Gila Watershed.

Each Friday through the end of March, we will post a new essay in this series. Next up: Jeff Clark on identities, worlds, and ideologies.