- Home

- >

- Preservation Archaeology Blog

- >

- Life of the Gila: Mapping Identities and Worlds ov...

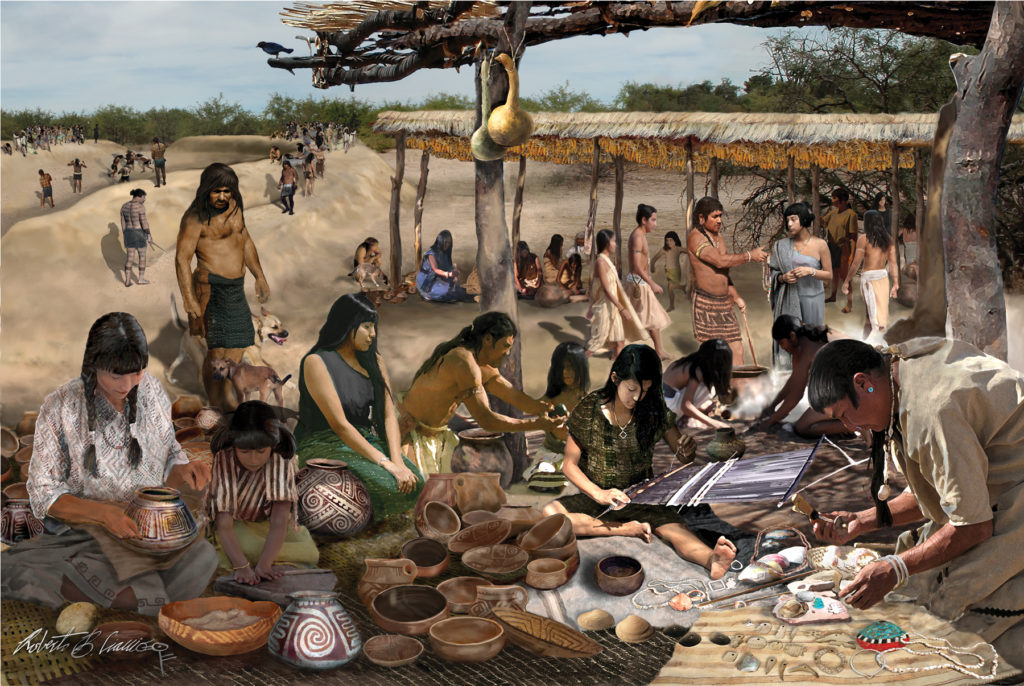

(February 14, 2020)—From Indigenous histories and from archaeology, we know a great deal about people’s lives in the southern Southwest from about 500 to 1450 CE. We know that life was rich and challenging; stable in some aspects and ever-changing in others.

Archaeology Southwest’s latest holistic research project seeks to understand how groups of people living in the Gila Watershed saw themselves and their worlds over that millennium. How did groups mark belonging and separateness—how did they express their identities to insiders and to outsiders? Which aspects of identity are discernible when we closely examine the objects and structures they left behind? How did these identities both persist and change across almost 10 centuries before European contact?

Ideally, we would document evidence of those changes and constancies using a massive archaeological database that covers all of the Southwest. That doesn’t exist—yet.

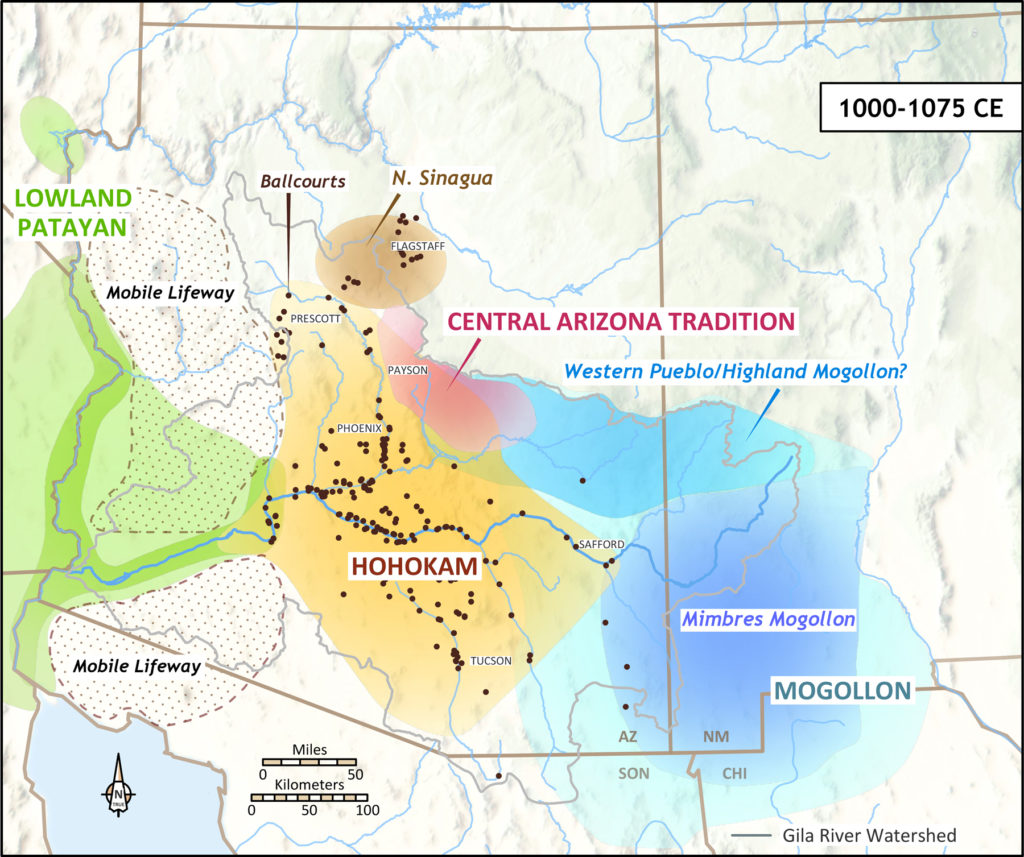

Nevertheless, we still believe that undertaking such a large-scale synthesis has great value. To begin this process, Archaeology Southwest’s research staff considered some of the concepts we explain below. Over the course of several months, we drafted maps showing group identities across the landscape and how those changed through time.

To continue that process, we reached out to 40 archaeological experts and 11 tribes with ties to the Gila River Watershed. We asked them to spend April 30, 2019, at the Bureau of Land Management’s National Training Center in Phoenix, where, as a larger group of experts, we beat up our draft maps (or, more politely: we commenced expert-guided synthesis). Attendees included 27 archaeologists and seven representatives from four tribes.

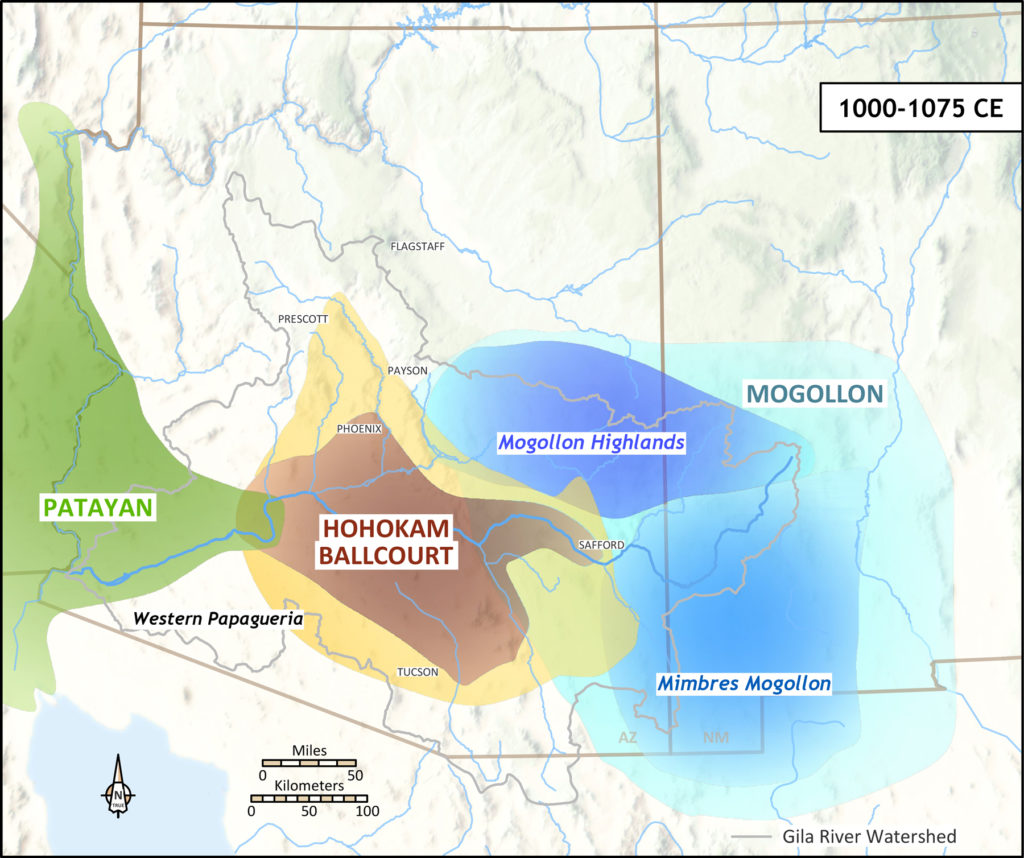

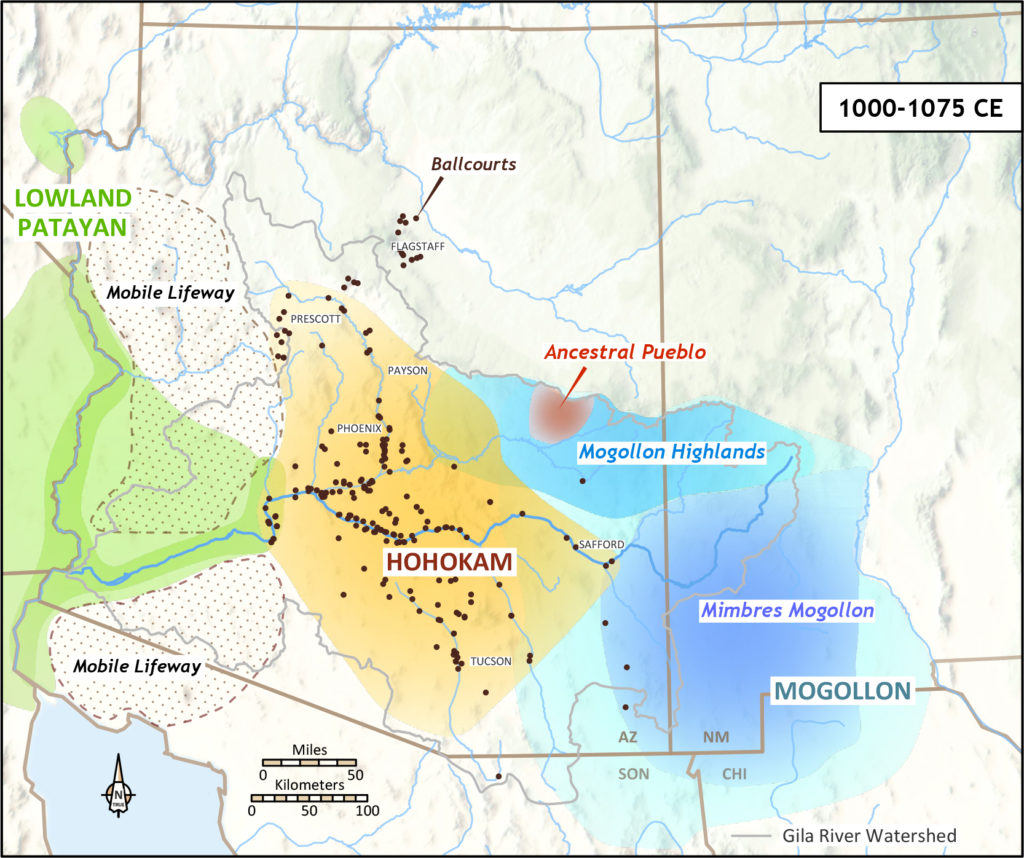

This was no small task. The Gila River Watershed encompasses more than 58,000 square miles, including all of southern Arizona, a good chunk of southwestern New Mexico, and parts of northern Sonora, Mexico. This area also encompasses all of the Hohokam archaeological culture and much of the Mogollon. It includes large portions of the Lowland Patayan, Sinagua, and Prescott “cultures” that are poorly documented or ambiguously defined, or both.

We knew there would be disagreement over particular details, but we had faith that we would come away with a broad understanding of change through time and what that revealed about shifting identities and worldviews. Over this series of blog posts, and in a special issue of Archaeology Southwest Magazine, we’ll share what we’ve learned.

BACKGROUND CONCEPTS: Identities, Worlds, and Ideologies

By 700 CE, many of the basins and valleys of the Gila Watershed were inhabited by agricultural groups that had well-defined territories and local traditions. These traditions were probably associated with group identities that were largely based on places—village, irrigation community, valley.

Identity (this section written by Preservation Fellow Leslie Aragon)

What do we mean by “group identities,” or even “identity”? Identity is an active social construction that is malleable, has many facets, and occurs at varying scales. People have many identities simultaneously, and any of them may be called upon as needed, based on the social context—we are continually reconstructing and renegotiating them. This should make sense when you think about the labels you apply to yourself and what those reveal about how you see yourself and your relationship to others in any given moment or social situation.

Some identities are based on our families and the people we interact with. These identities are generated from direct relationships that we have with other people. But we belong to some kinds of groups without necessarily having direct interactions with every other member. Such identities are based on perceived similarities with socially defined categories or social roles—teacher, international fan club member, conservationist. They may also be based on place—belonging to a village, a valley, a country.

How do we apply these concepts to the past? What kinds of group identities might be visible in the archaeological record? And how might we recognize them with the limited set of data available to us?

How do archaeologists infer identity from material evidence?

-

- Designs on pottery

- Way of making pottery

- Petroglyphs

- House forms

- How people structured their settlements (how groups of dwellings and open spaces were organized)

- Ceremonial objects

- Ceremonial architecture

- Ways of treating the dead

When we examine the things people made and built in order to infer aspects of identity, we think about the different ways that different types of identity are expressed. Some expressions of identity are very visible. They are displayed in order to convey messages about group membership or shared values and ways of thinking (ideology)—clothes, hairstyles, body modifications, cars.

Some expressions of identity are less visible. These are usually evidence of the ways people have learned to do and make things within families or task-oriented circles; they are not meant to convey information or signal something to larger groups of people. An example might be different family traditions of making marinara sauce—the end result is more or less the same, but the exact recipe and few ingredients might vary based on careful instruction passed on from generation to generation. Archaeologists might be able to figure out the presence of a “secret family recipe” by chemical analysis of the finished product or by digging in household garbage to find the remains of specific herbs and spices. They would also be able to find other markers of latent identities by examining the cooking pots and serving bowls—the way these pots were formed, the specific mix of materials to temper the clay, and the polishing patterns on the vessel surfaces.

By examining such patterns, we may recognize ideologies—broad, shared ways of thinking and viewing the world—that brought people together across larger areas. In the case of the Gila Watershed, these ideologies were associated with identities that integrated multiple villages, communities, and valleys. Because of that, we characterize these identities as “inclusive.”

Culture Areas and Worlds

In parts of the Gila Watershed, groups shared lifeways, basic social organizations, and traditional technologies. People built, made, and did things in similar ways that created patterns in artifacts, architecture, and site layout. These patterns of doing and making things in similar ways across specific local and regional landscapes are what archaeologists have defined as “archaeological cultures” or “culture areas.”

Archaeologists working in the American Southwest have a long and complicated relationship with the culture areas they have defined. After nearly a century of debate, the prevailing attitude seems to be that we can’t live with them, and we can’t live without them. American Indian groups have an even more skeptical view of archaeological cultures—understandably so. Those labels do not reflect the richness of lived reality nor the diversity of languages and practices people experienced, and they are not meant to. Terms such as “Hohokam” and “Mogollon” are not likely to fall out of use soon, though. Stuck with these terms and their associated artifact and architectural distributions, there has been a renewed effort to better understand what they actually represent.

What is a “world”?

-

- A large geographic area

- Comprising numerous cultural and linguistic groups

- That share basic ways of living, world views, and fundamental beliefs about how to live

- Worlds can connect, collide, overlap, and disintegrate

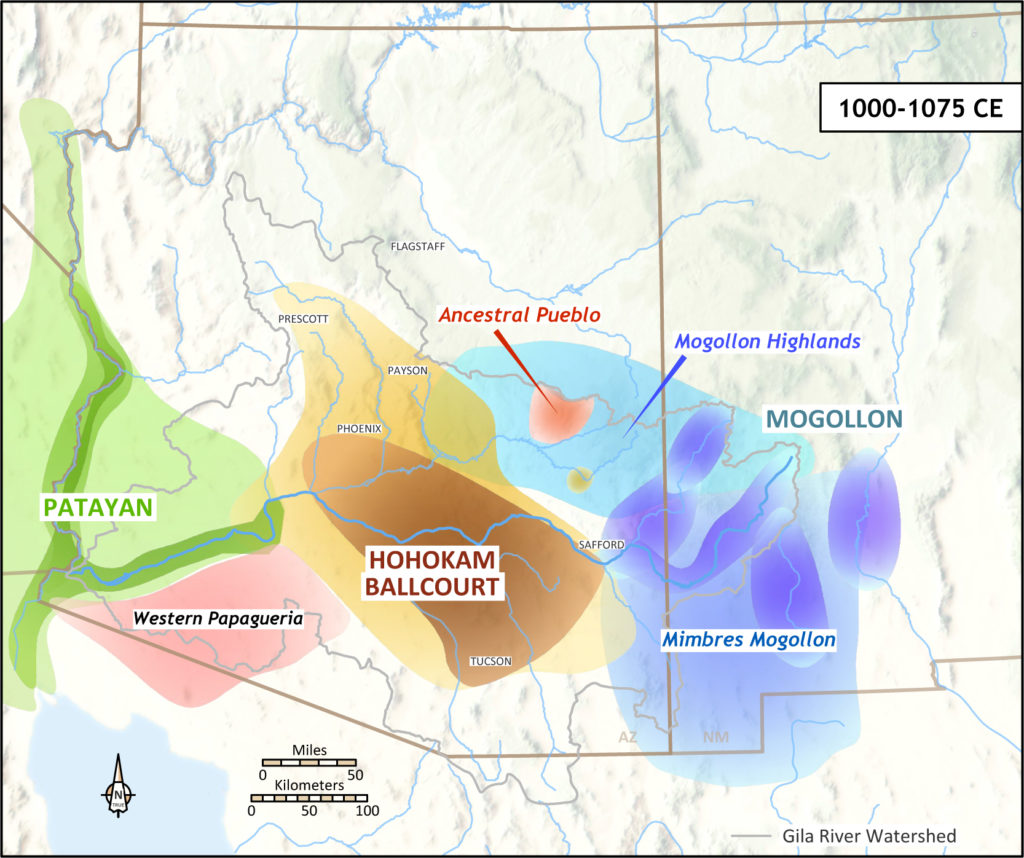

For our research team and others, it is useful to think of “worlds.” This term has been productively applied to the Ancestral Pueblo World, which probably included culturally and linguistically diverse groups of people over a vast landscape. Those people signaled their identities as members sharing certain beliefs in distinct material ways. As we continue with this blog series, my colleague Leslie Aragon will discuss the Hohokam Ballcourt World and the Hohokam Platform Mound World; likewise, Aaron Wright will introduce the Patayan World; and Karen Schollmeyer will consider whether the term applies to the Mogollon region, and to what is known as the Mimbres archaeological culture in particular. Finally, I’ll share our ideas about the Salado Phenomenon.

What do we mean by “world”? In essence, a world is a large area that contains different cultural and linguistic groups that still share basic lifeways and worldviews. During times of high inclusivity—times when groups are very connected—worlds coalesce politically, economically, or ideologically, or in some combination of those. The concept is usually applied in the study of empires and nation-states, but it can be scaled to traditional societies.

How do archaeologists define a “world” with material evidence?

-

- Basic subsistence strategies (ways of making a living, getting food, having shelter, and so on)

- Artistic genres expressed on material culture

- Long-distance exchange

- Ceremonial/public architecture

- Food remains reflecting cuisine

- Basic mortuary practices

- Traditional technologies reflected in tools and domestic construction (in traditional societies)

- Organization of domestic space

When worlds fall, when economies fail, when ideologies decline—that is when worlds disintegrate into numerous localized factions. Even during these disconnected times (often called “dark ages” or “intermediate periods”), some ideal of unity survives. Moreover, worlds may overlap and collide. Where and how they do is of great interest to anthropologists.

RESULTS: Mapping Past Worlds

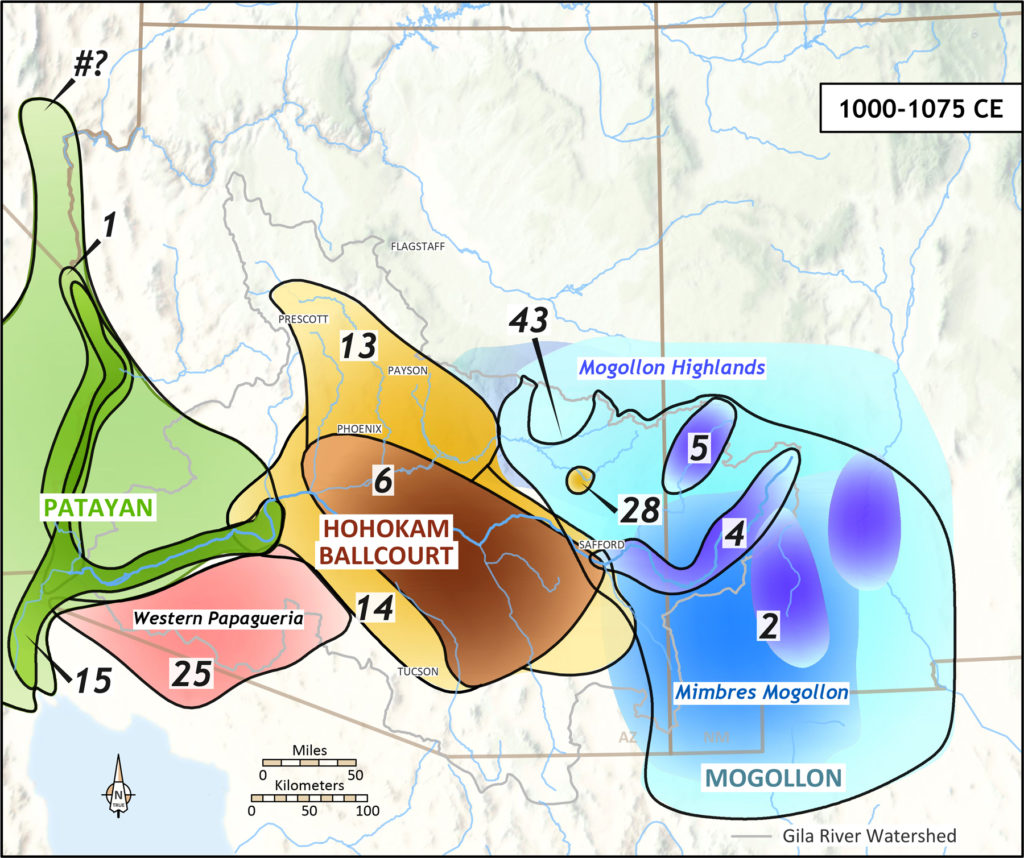

With this basic framework in mind, and with our in-house drafts of “identity” maps in hand, we met our panel of experts in a well-appointed conference room at the Bureau of Land Management’s National Training Center in Phoenix. The assembled group spent a very intense day painstakingly mapping the ebb and flow of identity throughout the Gila River Watershed century by century, from 500 to 1450.

In the morning, we broke into small groups based on geographical and culture-area expertise. These break-out groups strived to reach consensus within their respective areas.

In the afternoon, the rubber really hit the road. The entire group reconvened to compare and contrast maps, period by period. As groups reported in, John Welch and Stacy Ryan furiously took notes, and Catherine Gilman tried admirably to keep up with the numerous spatial adjustments while doing GIS on the fly!

|

|

As we anticipated, debate primarily focused on the boundaries of Hohokam, Mogollon, and Patayan along the Gila River or in areas where data were sparse. Some experts were comfortable with boundaries overlapping during the same interval, interpreting these as zones of co-residence and cultural mixing. Others wanted to see sharply defined lines on the map.

During times of maximum inclusivity—when people across a broad geographical area seem to have been sharing big-picture ideas about how to live, make things, and understand their world—large-scale identities mapped pretty well onto culture areas. This is true of the Hohokam Ballcourt World (700–1100) and the Classic Mimbres World (1000–1130) in the eastern Mogollon area.

This is no coincidence, because these culture areas were largely defined by the distribution of ceremonial architecture, painted pottery, and mortuary practices that reflected the inclusive ideologies associated with these worlds. For such connected and perhaps enlightened periods, the experts generally agreed on Hohokam, Mogollon, and Patayan boundaries, quibbling over minor territorial adjustments.

Much more problematic were intervals when large-scale ideologies were absent or in decline, especially in areas where we have considerable amounts of data. Here, the maps became extremely messy, reflecting the reemergence of numerous local traditions that had never really disappeared.

Such times of economic and social upheaval were probably difficult for people living in these regions, as well. The “messiest” period or “dark age” in the Gila River Watershed was from 1130 to 1250, after the collapse of the Hohokam Ballcourt World and the Classic Mimbres World. In this era, virtually every valley or basin was associated with at least one, often ill-defined (at least materially), identity. The inhabitants of long, linear river valleys such as the San Pedro and Verde probably had multiple localized identities up and down the river.

Finally, the interval from 1250 to 1300 created confusion among our experts, not only in terms of how to delineate spatial boundaries, but also in terms of how to best describe this interval. This was the time of the Great Drought, when associated population movements dramatically reconfigured the social map across the Southwest.

By 1300, the dust had settled across the southern Southwest, so to speak, and our maps became more coherent. At this time, people were aggregating into large villages, and depopulated buffer zones were opening up between some groups. We and our experts also recognized the emergence of new regional ideologies and entities associated with platform mounds and Salado polychrome pottery. These ideologies are not as coherent from an archaeological perspective as the Hohokam Ballcourt or Classic Mimbres Worlds, however. Debate among the experts regarding this interval was not so much about where boundaries were, but what they meant.

The zone of overlap between Salado pottery and Hohokam platform mounds was an area of particularly intense debate. Some thought that any attempt to compare the Hohokam Platform Mound World and the Salado World would be unproductive. These experts felt there was simply too much variability in the area where people were predominantly making and using Salado pottery (from the Phoenix Basin to the Mimbres Valley) to call this area a world or a coherent identity. I believe the Salado was an ideology that connected worlds within the Gila Watershed.

Another obstacle was data unevenness across the Gila Watershed. The Lowland Patayan World was relatively easy to map because so few data are available. I think this area will be broken down further as more information is acquired. At the other extreme, the tremendous amount of Cultural Resource Management work in the Hohokam region has produced so much data that a complicated mosaic of local traditions and identities is more readily apparent. Few archaeologists have a full grasp of this immense body of data; instead, they have tended to specialize in one or two valleys or basins. This specialization among Hohokam archaeologists is echoed in the multitude of identities we think existed in the past Hohokam world.

By the end of the day, most of us were exhausted—as was apparent in our glazed expressions. Much had been accomplished, but of course much more time was needed. There was a lot of brain power in the room, and many participants had already staked out competing positions that could be debated for days or weeks without resolution. Still, the time pressure forced us to be decisive and to rely on our collective knowledge at an intuitive level without being too pedantic about the details.

We have since undertaken follow-up meetings with individual participants that enabled us to flesh out more details. Revisions to the original maps are almost complete, and we will soon be sending those out for review to all the participants for a final round of feedback.

We hope you’ll continue to follow our “Life of the Gila” posts. The promised issue of Archaeology Southwest Magazine should be going to print later in 2020.

Each Friday through the end of March, we will post a new essay in this series. Next up: Aaron Wright on the Patayan World.

Explore the News

Related to This

-

Post Life of the Gila

-

Project Fluid Identities

-

Culture Sinagua

-

Culture Pataya

-

Culture Hohokam

-

Culture Mogollon

-

Culture Ancestral Pueblo

-

Culture Trincheras