- Home

- >

- Preservation Archaeology Blog

- >

- Life of the Gila: The Patayan World

(February 21, 2020)—Several years ago, a former archaeology professor of mine asked me, “What is this Patayan thing anyway?” After taking a moment to collect my thoughts, I responded with the kind of elevator pitch you might hear at some archaeological round table: “A Formative period archaeological culture that straddled the lower Colorado River, was quasi-agricultural, crafted paddle-and-anvil pottery, and fashioned geoglyphs on desert pavements and petroglyphs on rock faces.”

Wow. Perhaps the only thing drier than that description might—fittingly—be the low deserts where Patayan archaeology prevails. That exchange got me thinking about how archaeologists talk about the Patayan concept. And then I thought, how should we think about it?

“What is this Patayan thing anyway?”

First, some basics. As I’ve shared in a previous post, Patayan (pah-tah-yáhn) is an Anglicization of pataya, an Upland Yuman (i.e., Northern Pai) word that translates roughly as “ancestors.” “Patayan” is thus an adjective, so be wary if you ever read or hear about “The Patayans.”

Sometimes archaeologists oversimplify things, confuse pottery sherds for people, and generally have a hard time connecting living people with their ancestors. At any rate, we owe the Patayan nomenclature to Lyndon Hargrave and Harold Colton, who in the 1930s were looking for a way to describe a material culture they were finding on archaeological surveys in northwestern Arizona. At that time, the appropriation of Indigenous terms for “ancestor” was standard practice in Southwest culture history—recall that Hohokam derives from Huhugam, “those who have perished” in the O’odham language, and Anasazi owes to ‘Anaasází, “enemy ancestors” in the Diné (Navajo) language.

Prior to Hargrave and Colton, Harold and Winifred Gladwin of the Gila Pueblo Foundation had designated the paddle-and-anvil pottery of northwestern Arizona as “Yuman.” Malcolm Rogers, a researcher affiliated with the Museum of Man in San Diego from 1928 to 1945, also referred to some archaeological material along the lower Colorado River and in the deserts of southern California as Yuman.

In a way, Rogers and the Gladwins were implying an uninterrupted bridge between contemporary Yuman-speaking tribes and an older, “prehistoric” culture. Although Hargrave and Colton believed that much of the archaeological material in northwestern Arizona was ancestral to at least some Yuman-speaking communities, they did not presume to draw a direct link to any one of them, and they did not want to exclude other linguistic groups whose material cultures contained Patayan elements. The Cupan-speaking Cahuilla and Numic-speaking Chemehuevi, for instance, crafted varieties of Lower Colorado Buff Ware, a paddle-and-anvil, buff-firing pottery archaeologists associate with Patayan material culture.

OK, but…what IS it?

If not Yuman, then what is this Patayan thing after all? Is it a culture, people, tradition, or something else?

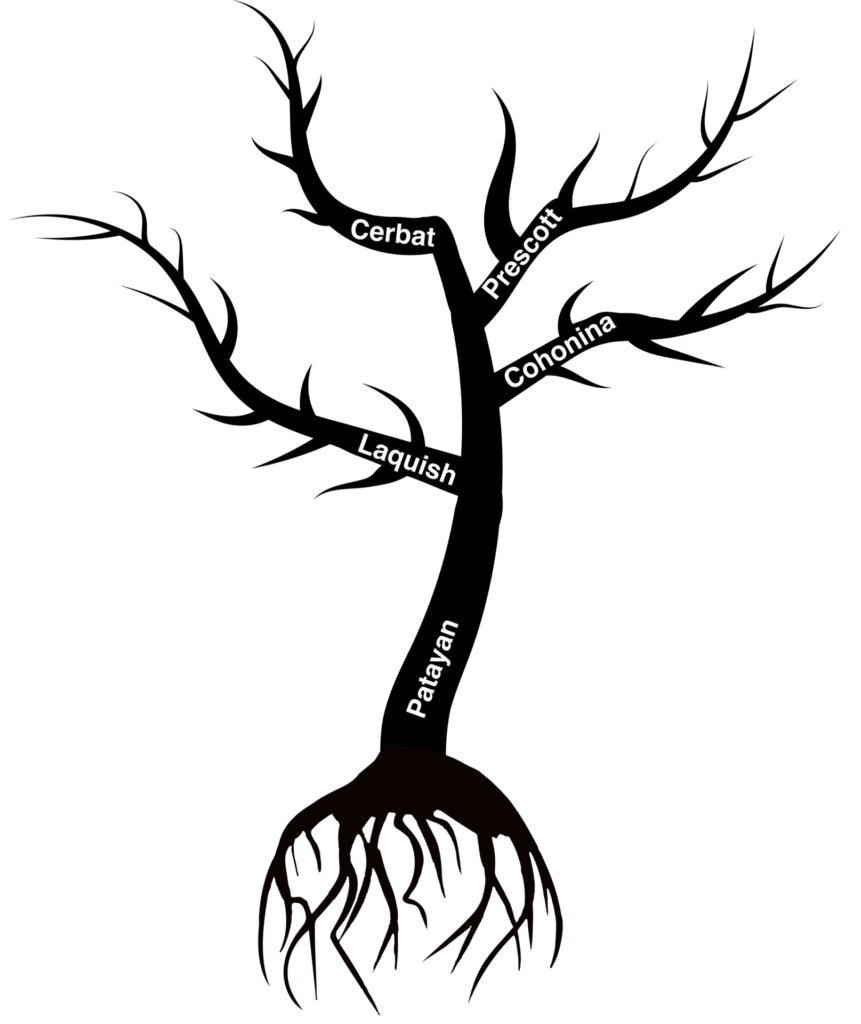

Colton and his acolytes conceptualized it as a culture root, from which various branches sprang up, such as Cerbat, Cohonina, Prescott, and Laquish. Albert Schroeder thought about it similarly, yet differently. In his view, Patayan was a stem that sprouted from a primordial Hakataya root (from the Hualapai word ha-kataya, “backbone of the river”). Schroeder’s Patayan stem grew out of the uplands of northwest Arizona, where Hargrave and Colton first identified it. Laquish, centered on the lower Colorado and lower Gila Rivers, was a separate Hakatayan stem.

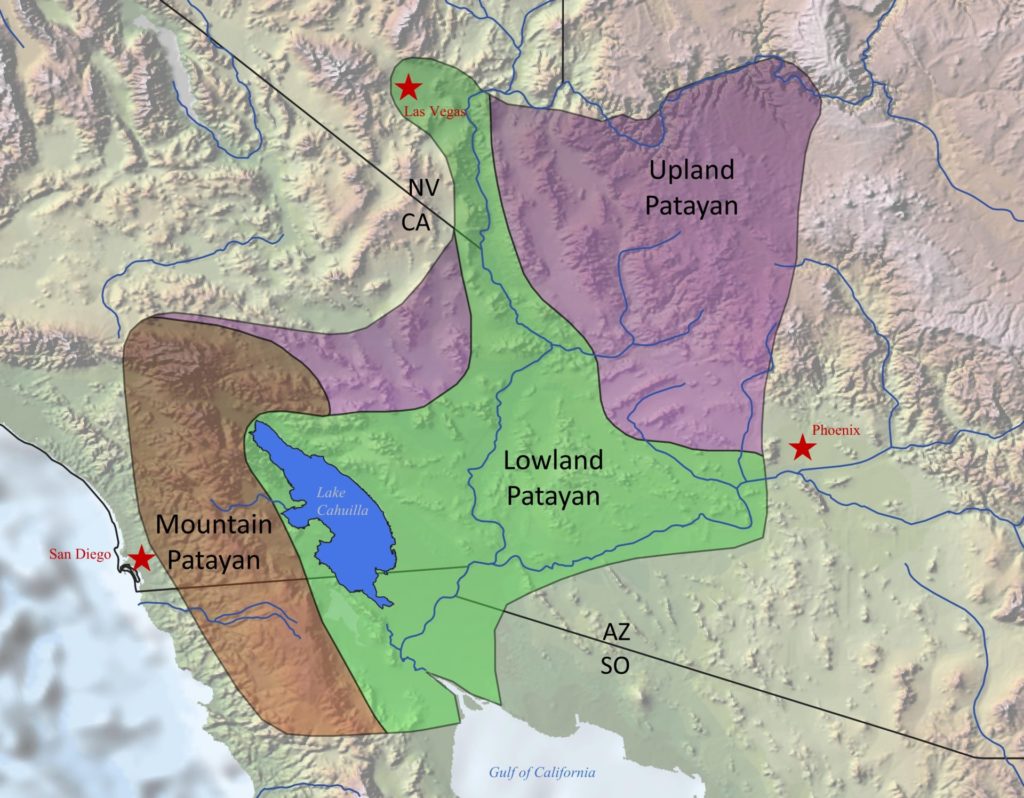

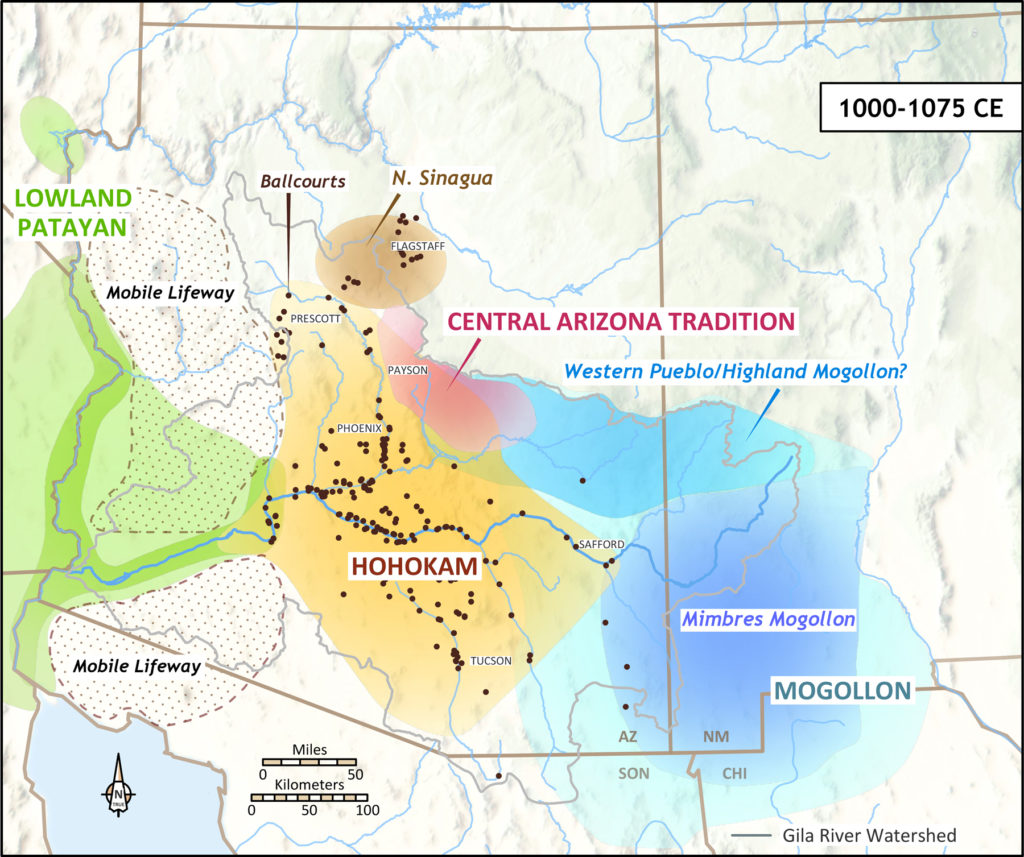

Colton and Schroeder’s visions of Patayan culture were explicitly evolutionary, in the sense that they conceptualized a parent culture that, over time, diverged into distinct cultural units—akin to the process of speciation in biology. Bob Euler and Michael Harner presented an alternative taxonomy that did not assume such an evolutionary relationship. Although they never published their framework, they recognized regional variants of Upland Patayan in northwest Arizona, Mountain Patayan in southern California, and River or Lowland Patayan along the lower Colorado and lower Gila Rivers. This scheme recognizes variation across space but does not necessarily assume divergence through time. It leaves the explanation of similarity and difference as an issue of research.

Whether we accept them or not, the various cultural taxonomies archaeologists have developed underscore that a wide range of things, sites, and images—material culture, so to speak—and the lifeways to which they attest have been subsumed under the Patayan umbrella. And this has created a great deal of confusion, because Patayan archaeology in one place often looks quite different that Patayan archaeology in another.

But there are two common threads that tie it all together: pottery and ground figures.

Archaeologists consider three pottery types—Lower Colorado Buff Ware, Tizon Brown Ware, and Salton Brown Ware—to be distinctly Patayan. The chief differences among them are the types of clay and temper potters used, which were a matter of resource availability more so than cultural preference. Interestingly, the distribution of each pottery ware closely follows Euler and Harner’s Patayan model—Salton Brown with the mountains of southern California, Tizon Brown with the uplands of northwestern Arizona, and Lower Colorado Buff with the lowlands along the rivers and around the Salton Sea (Lake Cahuilla).

It is this spatial cohesion in pottery that really defines what has been regarded as the Patayan culture area, a broad region stretching from Phoenix to San Diego, Las Vegas to the Gulf of California. This vast area covers different environments and topographies, some of which were amenable to agriculture and others not so much. This environmental variability necessitated different subsistence practices and settlement organization, which helps explain why Patayan, as an archaeological construct, essentially represents different lifeways. Along the rivers and around hand-dug wells, people farmed; around Lake Cahuilla they fished; and in other places they honed their attention around the seasonal availability of desert plants and animals.

But is Patayan just pottery? No. I believe ground figures (geoglyphs and intaglios) are the other tie that binds this Patayan thing together. Ground figures are not unique to Patayan archaeology per se, as they are found on all six of the planet’s habitable continents.

Yet this is exactly why the ground figures in the American Southwest are so compelling: people could have made them just about anywhere, but they didn’t. Perhaps more importantly, ground figures are found predominantly within the same range as the Patayan pottery types. Ground figures are an important part of the Patayan package because they reveal that this is not just about pottery. Although we don’t know exactly why they were made, most archaeologists agree that ground figures are emblematic of the spiritual lives of the people who made them. They not only show that certain religious elements were shared widely, but also that people observed and expressed those beliefs through similar ritual practices.

The Patayan World

So, today, how should we envision this Patayan thing? Lately, I’ve been thinking about Patayan not as a culture, but as a world, a Patayan World. The “world” concept allows us to conceptualize the archaeological pattern as one of shared beliefs, customs, and traditions brought about and fostered by the interaction of people of different cultural backgrounds and languages.

We know this was the case during the 1700s and 1800s, a time archaeologists include within the Patayan III period. At that time, Yuman, Cupan, and Numic speakers lived within the Patayan “culture area,” made Lower Colorado Buff Ware, organized themselves into similarly arranged rancherías, and engaged in essentially the same subsistence practices. From a material culture perspective, they appear identical, and yet they were culturally and linguistically distinct.

Similarly, ground figures are most abundant within the territory of Yuman-speaking tribes, but they spill over and onto the traditional lands of neighboring non-Yuman speakers, such as the O’odham and Hopi, who presumably made them. As with Patayan pottery, ground figures are strongly associated with ancestral Yuman traditions, but they transcend cultural and linguistic boundaries.

I agree that most Patayan material culture and sites are ancestral to today’s Yuman-speaking communities. But there is not just one Yuman culture or language, there are many—Quechan, Piipaash, Mojave, Cocopah, Kumeyaay, Yavapai, Hualapai, Havasupai, Paipai. I envision the Patayan World similarly, a network of social relations among culturally and linguistically similar yet unique communities across a wide swath of the American Southwest.

We may not be able to see these cultures or hear their languages with our trowels and transits, but history shows that the Patayan World included people of different cultures and languages, and we should assume that was the case in the deeper past, as well.

Each Friday through the end of March, we will post a new essay in this series. Next up: Leslie Aragon on the Hohokam Ballcourt World and the Hohokam Platform Mound World. Previously, Jeff Clark wrote about identities, worlds, and ideologies. The series began with Bill Doelle’s introduction to the Gila Watershed.