- Home

- >

- Preservation Archaeology Blog

- >

- Life of The Gila: Mogollon—It’s Complicated

(March 6, 2020)—Graduate school social life is notorious for this: groups of nerds spending a lot of time sitting around arguing passionately about very, very specific implications of certain words that people in other fields either use in a completely different way, or care nothing about.

Among other words, my mentors in graduate school taught me early on to refer to the Mogollon archaeological culture area, but never to “Mogollon people.” And for once, this wasn’t—and isn’t—just an obscure semantic argument!

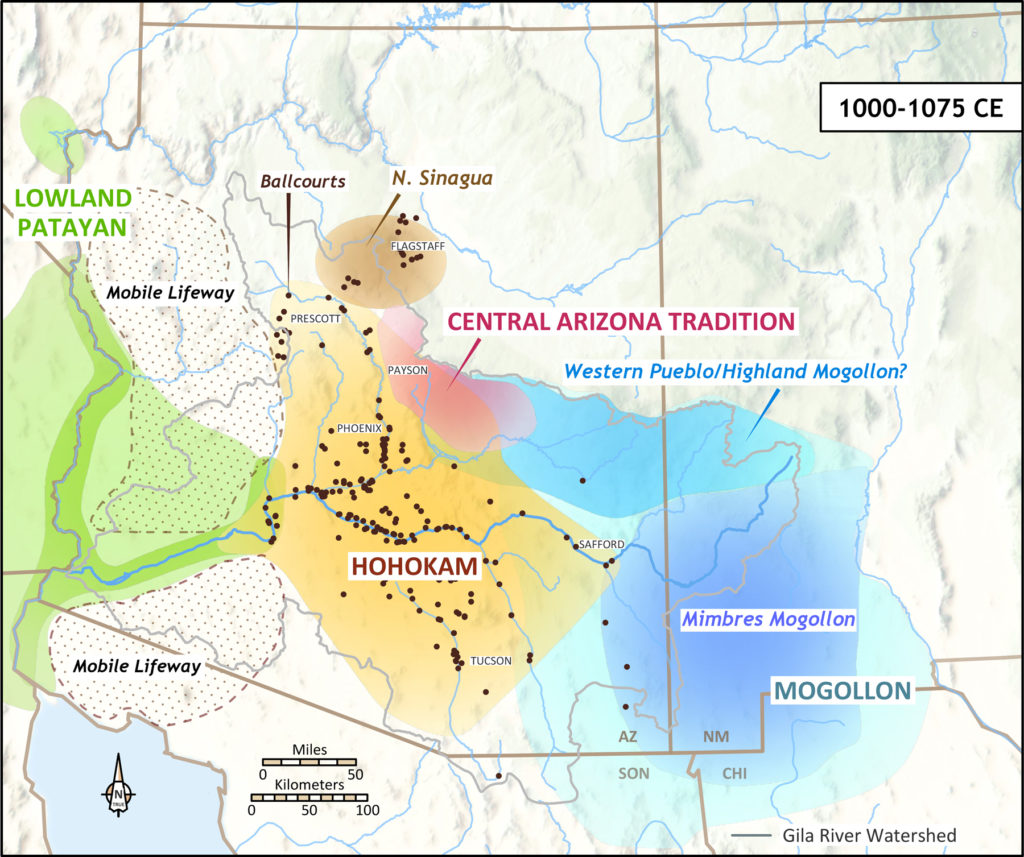

A quick glance at the area covered by the archaeological label “Mogollon” provides one reason why: it’s an area larger than some contemporary European countries that includes high-altitude pine forests, fertile river floodplains, and dry desert basins. It seems doubtful that people living in an area of this size would have spoken the same language, let alone made identical pottery, houses, or tools, or even thought of themselves as part of one cultural group.

The Mogollon Problem

Understanding Mogollon variability and what holds the region together as an “archaeological culture area” has been a challenge for archaeologists for quite some time. In the early 1930s, archaeologists already had a good idea of what material culture and sets of chronological changes they thought should define the Hohokam and Ancestral Pueblo areas, but had just begun to recognize Mogollon as “something else.”

In some ways, Mogollon resembled the Hohokam area before about 1000 CE, and the Ancestral Pueblo area after that, but it still looked different from either in some important ways. Unlike the areas around it, the Mogollon area continues to suffer from a bit of an image problem. Most people have some idea what Hohokam and Ancestral Pueblo archaeology looks like, but with the notable exception of the part of the Mogollon area archaeologists call Mimbres, most people don’t think about the “not-Mimbres” Mogollon much. In fact, most textbooks, encyclopedias, and other synthetic discussions of Southwestern archaeology either give this archaeological culture area only a cursory mention or leave it out altogether.

Let’s Do This: What We Know about Mogollon Lifeways

Along the Gila Watershed we’re focused on here at Archaeology Southwest, the Mogollon area lies upstream, stretching from Safford, Arizona, to the river’s headwaters in the Gila Wilderness in New Mexico. Much of our research here also references the closed-drainage basin of the Mimbres River just to the east. The Mogollon culture area also encompasses ephemeral streams flowing east into the Rio Grande from the Black Range Mountains; southern New Mexico and parts of far west Texas; and portions of the borderlands of southeastern Arizona, northeastern Sonora, southwest New Mexico, and northwest Chihuahua. (Note that the eastern part of this region, the Jornada Mogollon area, is not on our archaeological area culture map above—that mapping project is focused on the Gila Watershed.)

This is a much larger geographic area than the other archaeological culture areas we generally label on the landscape. Not surprisingly, then, there’s a lot of variation in the ways people lived across this vast swath of the Southwest. Historically, archaeologists have often divided this large area into “branches” with place-based labels, including Forestdale, Point of Pines, Reserve, Upper Gila, Mimbres, San Simon, Jornada, and Chihuahuan.

The standard definition of the Mogollon archaeological culture area relies on the houses people built and the pottery they made. Farmers in this vast region made pottery out of brown clay and formed their pots with a coil-and-scrape technique. The earliest villages consisted of deep, circular pit houses with ramp entryways, which people eventually replaced with deep, rectangular pit-houses grouped into villages of about 30 people. Residents replaced these pithouses with aboveground cobble-masonry pueblos by 1000 in much of the region (but not everywhere), and later still with adobe pueblos. People mostly buried their dead rather than cremating them (but not always), and religious spaces included large pit structures archaeologists often call kivas (although there are important exceptions to that, too, which I’ll discuss later).

All these exceptions to the general “Mogollon” pattern make it difficult for archaeologists to classify and label what we see on the landscape. But they also make this region much more interesting.

The people who were living in different parts of this large region and who made the archaeologically expected “Mogollon” houses and pottery did a lot of other things differently. In the San Simon Basin, for example, farmers lived in small villages of pithouses that were a little deeper—but not much deeper—than those used by their Hohokam neighbors just to the west. They made coil-and-scrape pots with brown clay, but their decoration looks just different enough from other parts of the Mogollon region that archaeologists give this pottery its own name, the San Simon Series.

This is an example of the complications. Pottery with distinctively Mimbres designs is far more common than Hohokam pottery on sites in the San Simon Basin, but recent archaeological chemistry studies suggest most of it was made by people living in the Cliff Valley to the northeast, and not by people in the San Simon. Around 1000, when large numbers of farmers in the drainages of the upper Gila and the Mimbres Rivers were aggregating into villages of large masonry pueblo buildings, the San Simon farmers dispersed out of their villages instead; after 1050 they built only scattered, single-room jacal (wattle-and-daub) houses that archaeologist Pat Gilman has interpreted as field houses—temporary, seasonal homes for farming, hunting, or gathering during limited times of year.

Did the highly mobile farming population of the San Simon drainage think of themselves as the “same people” as the much more sedentary farmers in the Mimbres Valley, who lived in pueblos of 300 people, made and used Mimbres Black-on-white decorated pottery exclusively, gathered in large plazas for group activities, and imported items such as macaws and copper bells from as far away as the Gulf Coast of Mexico?

This is a typical challenge to understanding the Mogollon area. It’s complicated—but interesting.

Important religious buildings also varied quite a bit through time and across the region archaeologists call Mogollon. Until about 1000, the most archaeologically identifiable religious structures looked a lot like the pithouses people lived in, but were clearly much larger. Unlike the kivas in the Ancestral Pueblo area to the north, these special pit structures in the Mogollon area didn’t have many specialized floor features (although some had an unusually shaped “lobed” entranceway, and many had substantial grooves in their floors). Many archaeologists refer to them as kivas, anyway.

In most of the region, villagers only used one kiva at a time in any given village, and larger villages had larger kivas, including “great kivas” 30 to 40 feet across (9–12 meters). Some villages had substantially larger kivas than they needed for the number of houses immediately around them, and these probably served a larger population living in the surrounding river basin area. When villagers stopped using a kiva building, they intentionally burned it down, collapsed its walls, and built a new kiva.

And THEN…

Around 1000, almost everyone in the Mimbres part of the Mogollon region stopped using kivas. They moved the sorts of activities previously undertaken in those buildings into several different spaces, including open plazas in their villages, extra-large surface rooms big enough for community gatherings, and small rooms in the centers of pueblos—and the functions of these small rooms changed over time, from dwellings into more symbolically charged, nonresidential spaces.

But people in other parts of the Mogollon region made different decisions about their religious architecture at this time. For example, in the Reserve, Forestdale, and Point of Pines areas, people continued to use large kivas for several centuries after their neighbors in the Mimbres River and upper Gila River valleys had stopped. In these northern parts of the Mogollon area, even great kivas were eventually too small to hold the populations of their villages. In the 1300s, some people moved their kiva structures to interior parts of pueblo buildings where they were hard to see and probably served an even smaller proportion of the people in the village, according to recent research by Katherine Dungan and Matt Peeples. In some parts of the area, kiva structures show influences from the Ancestral Pueblo area to the north, although they are also clearly related to the older Mogollon kivas.

What Does This Evidence Really Mean?

What do these similarities and differences in the houses, pottery, and religious architecture made by people in the Mogollon archaeological culture area tell us about their identities in the past? Much like the other archaeological culture areas we’ve discussed in this series, this area—in my view—encompasses groups of people who shared some basic ways of making important things (pottery, houses) and aspects of their religion (including the buildings archaeologists call kivas), and maintained important long-term social ties and relationships with each other over centuries.

People’s day-to-day relationships were with closer neighbors: others in their villages and in the valleys and large river basins where they farmed. These were probably the groups people would have identified themselves as being members of, and with whom they shared a common language and culture. Still, I suspect most of these people would have thought of themselves as having more ties to, and more in common with, other groups in the area archaeologists see as “Mogollon” than most would have felt with people living in the Hohokam archaeological culture area.

Over time, cultural traditions governing things like the designs painted on pottery or whether houses should be semisubterranean pithouses or aboveground cobble masonry changed at vast scales and within valleys, but villagers kept farming along the Gila and other river systems in the Mogollon region. The patterns in material culture archaeologists recognize may have changed, but the day-to-day activities of farming, hunting, and gathering continued.

Was Mogollon a World? Stay Tuned

With all this variability over time and space, could we ever see a “world” in the Mogollon region similar to the Hohokam Ballcourt World or the Patayan World? Did people actively choose to show group membership with highly visible material culture at a scale larger than their local river basins? I think the Mimbres Classic period (1000–1130) may have been something like a “world.” I don’t want this to turn into yet another Mogollon discussion in which Mimbres takes over, though, so that’s a topic for another blog post…next Friday!