- Home

- >

- Preservation Archaeology Blog

- >

- Life of the Gila: Salado—Bringing Worlds Togethe...

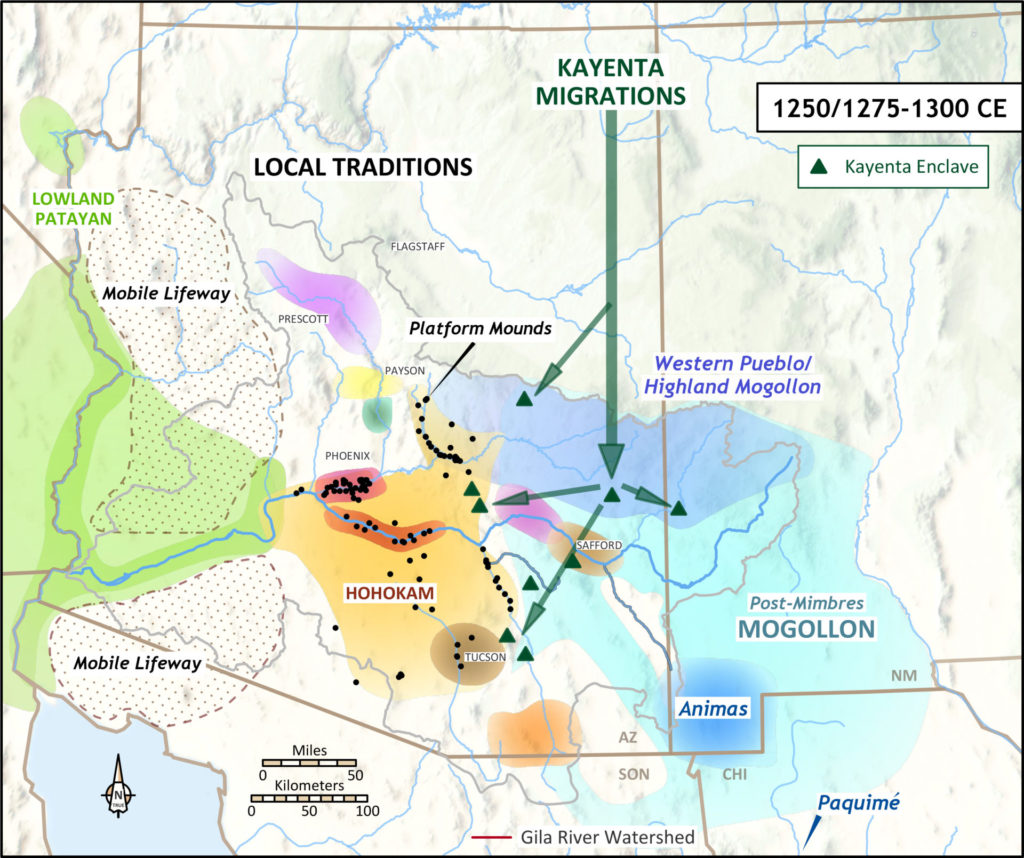

(March 20, 2020)—In the late 1200s CE, during a great drought, a few thousand people left settlements in what is now northeastern Arizona. They immigrated south toward perennial streams in the central and eastern Gila Watershed, where they lived alongside more populous, long-established local groups.

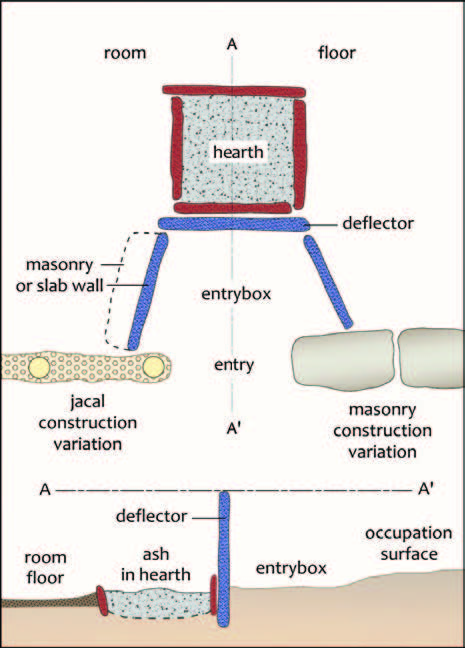

The immigrants made distinctive pottery and built distinctive architecture, just as they had in their homeland. Archaeologists use the term Kayenta to denote this pattern within a broader Ancestral Pueblo tradition. Based on distributions of perforated plates (tools Kayenta potters used), entry boxes (characteristic architectural features), and other latent identity markers (remember our earlier post—these markers reveal how people learned to do or make things), archaeologists have identified Kayenta enclaves in the eastern Hohokam Platform Mound World and western Mogollon World. The immigrants and their immediate descendants were a minority that formed a community in diaspora—more on that in a bit.

Interaction between local groups and immigrants and their descendants across generations is key to understanding what archaeologists call “Salado.” I believe Salado was an inclusive ideology that arose to alleviate ethnic tensions. It facilitated cooperation and trade in a multicultural setting.

Although Salado ideology may have emerged within the Kayenta community, it quickly spread to local groups who had long inhabited the basins and valleys of the central and eastern Gila Watershed. By the late 1300s, it had become the dominant ideology across much of this region, reaching into the lower Salt River valley of the Phoenix Basin and just beyond the watershed to the Mimbres Valley. Which groups—Kayenta descendants, local groups, or both—were responsible for the spread of this ideology to other areas is unclear.

Salado endured for more than a century. By the time almost all the large and archaeologically visible settlements of the Gila Watershed were depopulated, around 1400 to 1450, the ideology was no longer practiced.

Some Intellectual History

Since Salado was conceived more than 80 years ago—through the combined efforts of Erich Schmidt, Harold and Winifred Gladwin, Florence Hawley Ellis, and Emil Haury—it has continued to vex Southwest archaeologists.

Where first observed, in the Tonto Basin and adjacent highlands around the town of Globe, Arizona, the pattern was that of bold polychrome pottery, masonry architecture, and inhumation burial practice overlying pithouses, red-on-buff pottery, and cremations. The Gladwins posited a series of migrations: an earlier one from the Phoenix Basin, where people lived in ways that fit the Hohokam pattern, and one from the north, which created the second. In that model, Salado developed a unique culture in the Tonto Basin and adjacent highlands before moving out to other areas of the Gila Watershed.

A second model, developed by Emil Haury and based on evidence from Los Muertos, a large site in the Phoenix Basin, held that Salado was a hybrid culture resulting from close interaction between local Hohokam and migrant Pueblo groups living together amicably within the same settlements.

For 50 years, archaeologists debated what Salado was—and, more often, what it was not. Migration and replacement? Local development with little population movement? Something else?

New Data and New Frameworks Add to the Picture

Over time, archaeologists working in other valleys and basins in the watershed, beyond the supposed Salado heartland in the Tonto Basin, discovered other heartlands. Some important projects of the past 30 years have helped us better understand Salado. These include a massive Bureau of Reclamation project in the Tonto Basin during the late 1980s and 1990s, the Mimbres Foundation’s work at Salado sites in the Mimbres Valley in the 1980s, University of Texas at Austin’s work in the Safford Basin during the late 1990s (especially the Goat Hill site), and Patricia Crown’s 1994 regional synthesis of Salado polychromes. Since the early 1990s, Archaeology Southwest has been investigating Salado in the San Pedro Valley, Safford Basin, and other parts of southeastern Arizona into southwestern New Mexico.

Archaeologists are also armed with a battery of new analytical techniques—petrography, Instrumental Neutron Activation Analysis (INAA), and Energy Dispersive X-Ray Fluorescence (ED-XRF) spectrometry, among others. These help us to determine exactly where people obtained the raw materials they used to make pottery and stone tools.

Out of all this work, a number of nearly indisputable facts have emerged. (Archaeologists will always dispute.) We now know that people were making Salado polychromes in nearly every valley and basin in the eastern and central Gila Watershed. We also know that people were trading obsidian from the Mule Creek source (located in New Mexico’s upper Gila River valley) across much of the Salado region after 1300. Mule Creek obsidian was especially abundant in areas where people were making and using a lot of Salado polychrome pottery. (The lower Salt River valley is a notable exception.)

We also have more sophisticated theoretical frameworks for studying migration. Two key concepts that my colleagues and I have used are coalescence and diaspora. Communities in diaspora are migrant communities that share a cultural background, but are dispersed. These migrants often have left their homelands under duress, and are people in exile. Borrowing and reworking ideas developed by Steve Kowalewski, my colleagues and I defined coalescent communities as those composed of multiple cultural groups who share a place, also during stressful times. Coalescence and diaspora are contradictory and complementary organizations, depending on context. Diaspora emphasizes shared heritage regardless of spatial separation. Coalescence emphasizes shared place, regardless of cultural differences.

Canvassing the Salado Tent

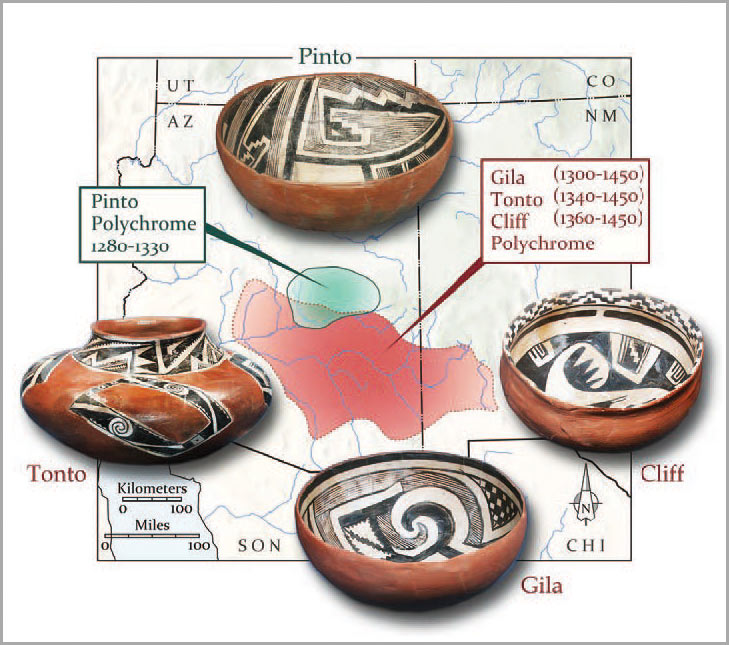

Salado encompasses too large of an area and too much diversity in artifacts, architecture, and burial practices to be considered a “world.” The only common material marker of the ideology preserved in the archaeological record across the central and eastern Gila Watershed is Salado polychrome pottery.

Although there is a fairly high degree of consistency in how potters made and painted these vessels, we know from geochemical analyses that people were making them locally in many places within the watershed. Kayenta enclaves are present in each, and there is direct evidence for Salado polychrome production in these enclaves. This makes sense considering the strong Kayenta connections we see in Salado pottery itself.

What doesn’t make sense to many archaeologists, however, is how the painted pottery tradition of an immigrant minority became so abundant across such a large and diverse area. How could so few outsiders have such a large influence on so many locals?

I think it’s because Salado polychromes and the ideas expressed on them transcended or connected worlds, without replacing the multitude of local traditions and identities within them. I’ll explain.

When we look at large settlements of the 1300s across the region, it’s clear from the abundance and ubiquity of Salado polychrome pottery that every household had some, regardless of cultural background or economic class. This suggests that membership in Salado was open and participatory. I think just about anyone in the watershed who wanted to be Salado could have been, while still maintaining other, more local identities based on kinship, place, and cultural origin.

Diversity seems to have thrived under a very large Salado tent. But why was the tent even erected? And by whom?

When Worlds Collided

If there was ever a time of duress in the Southwest, it was the late 1200s. The 25 years from 1275 to 1300 represented one of the most problematic periods for the experts in our mapping session because so much change—climatic and demographic—was occurring so rapidly. During this period, Kayenta and other migrants dropped off the Mogollon Rim and entered the Gila Watershed, an entirely different world—what the Zuni call “the land of everlasting sunshine.”

When these immigrants established enclaves in the San Pedro River valley, local groups still influenced by the Phoenix Basin Hohokam built walled settlements and platform mounds within them. At least initially, and especially in the northeastern Hohokam World, tensions between the enclaves and nearby local settlements were high. This was the first time in the Southwest when worlds truly collided.

At first, Kayenta immigrants made a version (Maverick Mountain) of the pottery they’d made in their homeland (Tsegi Orange Ware). Maverick Mountain pottery actively signaled Kayenta identity. Local groups continued to make or revived earlier red-on-brown and red-on-buff pottery traditions. After a generation of interactions among migrants and locals, tensions abated. We infer this from evidence of intense exchange between migrant (and migrant descendant) enclaves and nearby local settlements. An era of coalescence had begun.

At this time, we see widespread production of Gila Polychrome, which replaced local painted ceramic traditions (except in the western Tucson Basin and vicinity, where red-on-brown traditions persisted). It seems that the Kayenta and their descendants were producing most of the Gila Polychrome pottery, at least initially.

And these potters were doing something very interesting. They made the interiors of Gila Polychrome bowls using the same paint recipe and design scheme as a white ware (Tusayan) they had made in their homeland. But on the exteriors of these bowls, they added a red slip that emulated long-established red ware traditions of the Hohokam and Mogollon Worlds.

As an immigrant minority trying to maintain an identity, the Kayenta may have had more incentive than the locals to develop an inclusive ideology and associated pottery that was attractive to members of the Hohokam Platform Mound World—some of whom may have been marginalized within the hierarchical ideology associated with this world. At least initially, these two ideologies may have competed, but ultimately Salado prevailed, or the two ideologies syncretized, as our colleague Lewis Borck has discussed in depth. It is notable that many of the latest settlements (or construction episodes in existing settlements) are associated with large quantities of Salado polychrome pottery, but no platform mounds.

In the former Mimbres World, Salado may have entered more of an ideological vacuum that had existed since the collapse of Mimbres. Here, the competing ideology emanated from the emerging Paquimé World, which was also associated with considerable hierarchy. (Delving into that would be another blog post, though, and one better written by someone more knowledgeable!)

When Worlds Connected

Salado ideology peaked in the late 1300s, spreading east and west and ultimately becoming the dominant ideology even in the Phoenix Basin center. The Salado tent fostered coalescence, tolerance, exchange, and probably intermarriage. Lines between Kayenta, Hohokam, and Mogollon had become increasingly blurred, with groups from different heritages living alongside one another in the same settlements, just as Haury noted at Los Muertos.

During this time, potters made very large Salado polychrome bowls and jars adorned with richly symbolic painted decoration (Tonto Polychrome and Cliff Polychrome). The designs on these vessels were intended for viewing by large gatherings of people, probably associated with religious feasts.

By the end of the 1300s, the Salado polychrome tradition began to break apart into eastern and western variants approximately at the Hohokam–Mogollon boundary. This dissolution and decline of Salado is associated with the depopulation of large coalescent communities across much of the Gila Watershed at the time. The causes and extent of this upheaval remain a topic of much debate among archaeologists.

In a way, the view of Salado I’ve shared here is a coalescence of the models archaeologists proposed some 80 years ago. Both migrants and locals played essential roles in the development and spread of Salado ideology; Salado would not have emerged without intense migrant-local interaction. Although it may have developed within the immigrant community, local groups undoubtedly played a pivotal role in its subsequent spread, especially to the Phoenix Basin. (And I would be remiss if I didn’t note that Haury’s view of the Salado was more or less accurate.)

Our understanding of Salado today is more nuanced thanks to the greater body of data, computational power, enhanced analytical toolbox, and more sophisticated views of concepts such as ethnic co-residence, coalescence, and diaspora. Migrants can retain aspects of their identity and coexist amicably alongside local groups if inclusive ideologies are fostered and given time to develop. The Salado is a great example of this—a vast tent connecting worlds across the Gila Watershed for at least a century.

Explore the News

Related to This

-

Post Life of the Gila

-

Project Fluid Identities

-

Project The Edge of Salado