- Home

- >

- Preservation Archaeology Blog

- >

- Focus on the Field Crew: Charles Arrow

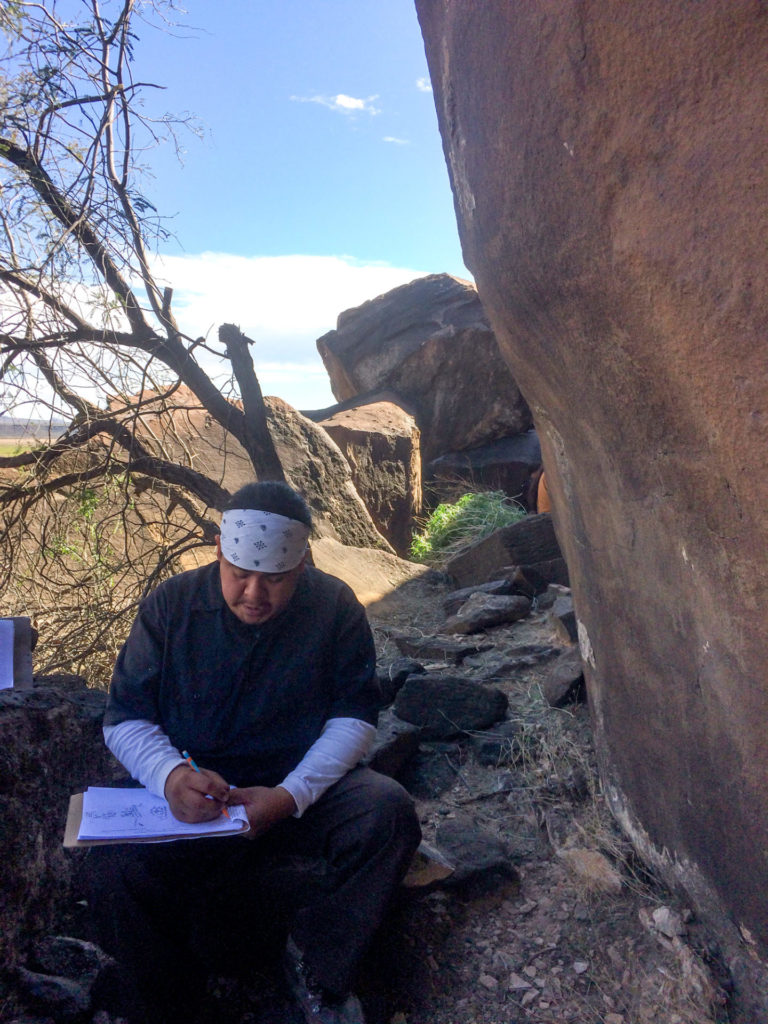

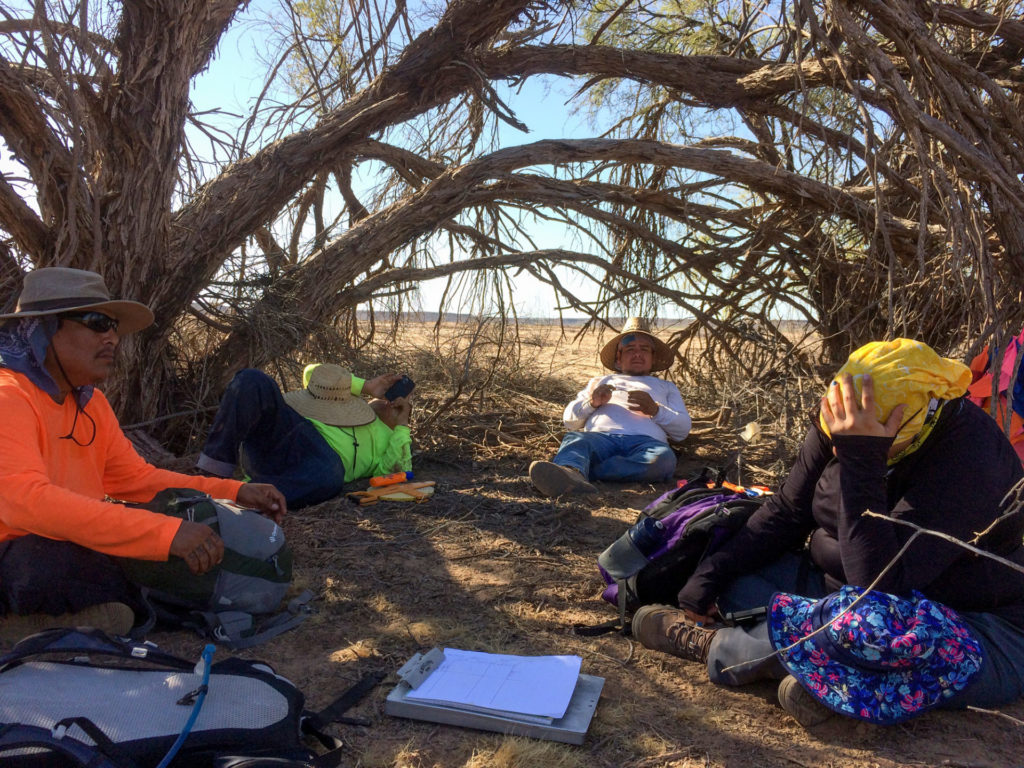

(April 17, 2020)—Continuing with the Lower Gila River Ethnographic and Archaeological Project’s (LGREAP) Focus on the Field Crew blog series, this week I introduce Charles Arrow. Charles is a member of the Fort Yuma Quechan Indian Tribe, and though currently living in Yuma, several years ago he spent a few years in Tucson. While there, he befriended someone in the cultural resource management industry, but little did he know that later on he, too, would be involved in cultural resources and heritage matters through LGREAP.

Charles has spent the past seven months documenting archaeological sites along the lower Gila River, but this wasn’t his first stint. He actually started the project at the end of the first field season, in March and April of 2019, which gives him a bit of seniority on the project. Charles learned of the project through his aunt Jerilyn Swift Arrow, a member of the Quechan Cultural Committee.

I met Jerilyn when the Cultural Committee joined several of us from Archaeology Southwest for a site visit to Texas Hill shortly after we added a major portion of this awe-inspiring landform to the organization’s preservation portfolio. Jerilyn and I talked about LGREAP, and she thought it might be something Charles would be interested in.

Lo and behold, she was right. Charles has been a solid member of the field crew ever since, and someone I’m fortunate to have met. In our interview below, you can get a sense of Charles’s honesty, humility, and cordial demeanor. It’s nice to be in the company of nice people.

Aaron: What is your first memory of archaeology, or artifacts, or anything of that nature?

Charles: My first real experience was with my buddy from Tucson. They would tell me when they got back from work what they were doing and things like that. They were doing a lot of work in Tucson, excavating things.

Aaron: They were doing cultural resource management?

Charles: Yeah. It was like a monitoring thing, it seemed like. They would just post up and watch the workers go through with their excavating equipment and then chime in when they saw something and stop there.

Aaron: Would they just tell you what they found?

Charles: Yeah. They would come back and tell me little things, like, “Oh, we found pottery stuff” and things like that. It was kind of interesting just to hear how close to the road, and how the town of Tucson was really just overlapping and burying all this other kind of history. That was cool, and I thought that was pretty interesting. They would always come back and go, “Oh yeah, we camped out here and were looking for artifacts and whatever, whatnot,” and they’d tell me about how they were hiking and stuff like that. It seemed pretty interesting at the time, but this was like, years ago before I even started working for you guys at Archaeology Southwest. It was interesting then. And then, that first season when I actually came out with you, that was just, like, mind-blowing. Besides all the hiking and such, I was just like, “Whoa, these are the actual sites where our people lived and congregated.” That was really cool.

Aaron: So what attracted you to this project in the first place?

Charles: What really got me into it was the [Quechan] cultural committee. It was a job opportunity that my aunt told me about. I know she was looking out for me to get me to do something because I wasn’t working at the time. I was sitting on my butt at home. She was like, “Hey, I got a job opportunity for you if you’re interested.” She explained that it was going back to our culture, and just a general cultural experience in the area. She didn’t really tell me what it entailed as far as the amount of exercise and stuff, but it was an interesting opportunity, so I jumped on it.

Aaron: How has your perspective on archaeology changed from when you first began that last season until now?

Charles: From then ‘til now…compared to the first season we’re not really doing anything too much different into this second season. It hasn’t really changed since that first season, but I have a really high interest in it. It’s interesting to see what we do find in the dirt, just looking around, just poking around really, and how much of that stuff is there, how old it is. It’s just pretty cool. I like what I do.

Aaron: What do you find to be the most interesting part of the project?

Charles: I’d say some of the villages we go to. Just looking around for artifacts, looking in the dirt for sherds and things like that. That’s probably the most interesting. Survey is okay. I understand that we have to cover a fair amount of ground, but when it comes down to it, actually just looking around in the dirt for artifacts.

Aaron: How does this project compare with other types of archaeological research you’ve read about or learned about from other people?

Charles: Really, when it comes down to it, I have my own personal perspective on it. I could read so much about different archaeological projects, but actually what it really comes down to is having my feet on the ground and actually looking around myself.

Aaron: What do you see being the value or long-term benefit of what we’re doing?

Charles: Actually having a record, a more detailed record. From what I understand from you, some of the sites we’ve been to, they’ve been documented but not documented as thoroughly as I would have thought people would have done back in the 1960s or whenever. I feel that we’re doing a really thorough examination of the area, and that’s pretty cool for me, because we’re actually going through and being thorough about it.

Aaron: In what ways do you see archaeology contributing to the preservation of traditional Quechan culture and heritage?

Charles: Well, especially with Archaeology Southwest, it’s like, we’re the only other people that I know of that are actually documenting stuff. Most tribes in the Southwest, it seems like, for the preservation of it, I don’t see my tribe doing a whole lot as far as preservation, as actually having people out there on sites and such. The cultural committee does do a bunch of stuff like that, but I don’t feel as though they do as much documenting of it. I didn’t even know cultural committee was a big thing, or actually was a thing until I saw Manfred [Scott, acting committee chair] and my aunt and the whole committee. I knew people were out there but I didn’t think they were doing as extensive work as what we’re doing now. That’s how I found that out.

Aaron: What aspects of Quechan history and tradition do you think we are not able to actually see through archaeological research?

Charles: It would be nice if everything had a label, if there was like a definite, like a direct correlation to my actual tribe, my actual people. It’d be cool to see Quechan writing on a pottery shard. That way we know it’s part of my history, but a lot of the stuff we find is pretty general I think. As for the pottery, it might have been just a method that they used. There is no definite “this is us,” you know. Something about some of the other pottery we find, it seems more specific to other tribes.

Aaron: What about the petroglyphs?

Charles: Apart from me being out here, in the Yuma area I’ve been recreating for a good time and I’ve never seen petroglyphs. I wouldn’t even know where to actually look for sites. But again, I didn’t have any real background with petroglyphs until I started working with Archaeology Southwest. I couldn’t decipher…I didn’t even know what a petroglyph was until we hit sites that actually had petroglyphs. I was like, “Whoa, this is cool.” I’ve never seen anything like that on my reservation. I never really had the motivation or information to know where they were.

Aaron: How do you think research and the conservation of archaeological sites and artifacts contributes to the teaching and preservation of traditional Quechan culture?

Charles: That’s the thing we’re going to have to start bucking up on our end as far as the tribe. We can document all we want to, but it’s going to take a good crew like the one we have to actually put that information out there to get more of a general interest in that kind of stuff. I feel that with the work we’re doing we can go out and try to influence the younger people and get them into archaeology and either history on the rocks or in the dirt. It’s going to a take a good push on our end to get people interested in things like that, I think.

Aaron: How does Quechan oral history and stories, how do they compare with the archaeology that we’re seeing on the lower Gila River? Do you think they are compatible, and if so, how?

Charles: Honestly, I don’t really have a whole lot of experience with the oral history as far as my tribe. I’m kind of ignorant when it comes down to that kind of stuff. I’ve only been able to learn more through your book, the one you had given me. I was just like, that kind of taught me a little bit about my history. But as far as that, I don’t even know. I didn’t really hear stories when I was growing up about our history and such. Maybe here and there, but I’m pretty ignorant when it comes to stuff like that, so I couldn’t tell you, really.

Aaron: How well do you think archaeologists and anthropologists, in general, have listened to the concerns and interests of Native communities?

Charles: As far as archaeologists go, I feel like they do listen really well. Like some of the military work sites out here, like YPG [Yuma Proving Ground], I’m pretty sure they seem interested, but I don’t think they really care when it comes down to it because there’s a lot of projects that go regardless of archaeologists and surveyors identifying sites before the government goes through and destroys them. I guess that’s a different question…

Aaron: Do you believe Indigenous communities should have more of a role in archaeology and why?

Charles: I think so. When it comes down to it, the areas we live in are our areas, and that’s our history. We should have more of a role because that’s our own personal history. It would be nice to have more Natives in archaeology, but with the times there’s a long…there’s a gap. Things are more modern, and there’s not a whole lot of general interest to preserve that kind of stuff…our history, I feel.

Aaron: So there’s a generational gap?

Charles: Yeah. A lot of our history is dying out. There are certain people on the reservation that do have information, like oral history and their understanding of what’s going on, but when it comes down to it a lot of people have lost interest. It’s just that the times have changed. Our language is dying out. There’s a lot of people on different reservations who don’t even speak their own language. We’re fading out, you know.

Aaron: Is there anything about our fieldwork that is fostering for you a closer connection to your tribe’s history?

Charles: Like I said, a lot of the places where we’ve worked, it seems like we’re in a general area where a lot of tribes congregated. To be able to tell the difference between them all, no I couldn’t tell, but like I said I don’t really have a whole lot of information as far as the history of my people goes.

Aaron: How would you like to see archaeology carried out in the future?

Charles: Honestly, I wish they had more of your work ethic. You’re thorough, you’re on it. I would like to see more people have your kind of mindset as far as preserving the history and the culture of what the land has to offer. I wish more people thought about it like you. I’ve heard a lot of different companies have archaeologists that are just kind of “meh.” It seems like they’re there more for a paycheck, for the most part. A lot of people don’t seem to have the kind of passion that you do. That would be nice to see more of.

Aaron: How has your experience on this project shaped any of your future goals?

Charles: Well, it definitely sparked an interest in archaeology for me. I would actually like to continue on with a higher education in anthropology or something. I wouldn’t know where to start. I have a general idea as far as fieldwork goes, but as far as schooling and actually being in a classroom, I wouldn’t know. I’m looking into it, but again I haven’t continued on with my education in…well, it’s been almost 20 years. But working with you, I’ve definitely developed an interest because I wasn’t really into school. For my high school years, I was just there, but it was boring to me for the most part. But now, with what we’re doing, I’m kind of leaning more towards getting a higher education through college or whatnot. I’m leaning into that. I’m actually looking into different options and seeing how I can get in. I’ve been out of school for almost 20 years, and this is the only thing that has really caught my eye, you know, or my attention.

Aaron: Right on. Well, that’s it for the interview. You got any final comments…final last words or anything?

Charles: Uh…Aaron’s a goat [chuckles]. I mean, I’m just grateful to have been able to be on this project with you as long as I have been. I feel it would’ve been cooler to have had the opportunity earlier, like a couple years earlier. It would’ve been nice to help you out then, but it is what it is and we are where we are. But I’ve definitely enjoyed working with you and Archaeology Southwest and the crew that we have. It’s really nice to have them out there, as a group from a certain tribe. It’s really nice to see that kind of interest in trying to preserve that, and actually being out there and representing our tribe. That’s really cool…I really enjoy that.

This three-year study was awarded a Collaborative Research Grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities (RZ-255760). The NEH is an independent federal agency created in 1965. It is one of the largest funders of humanities programs in the United States and awards grants to top-rated proposals examined by panels of independent, external reviewers. Any views, findings, conclusions, or recommendations expressed in this study do not necessarily represent those of the National Endowment for the Humanities.