- Home

- >

- Preservation Archaeology Blog

- >

- Focus on the Field Crew: Jason Andrews

(May 1, 2020)—The Lower Gila River Ethnographic and Archaeological Project’s (LGREAP) Focus on the Field Crew series has really shown me the value of listening to people. And I’ve not just been listening—asking has been a critical part of this experience.

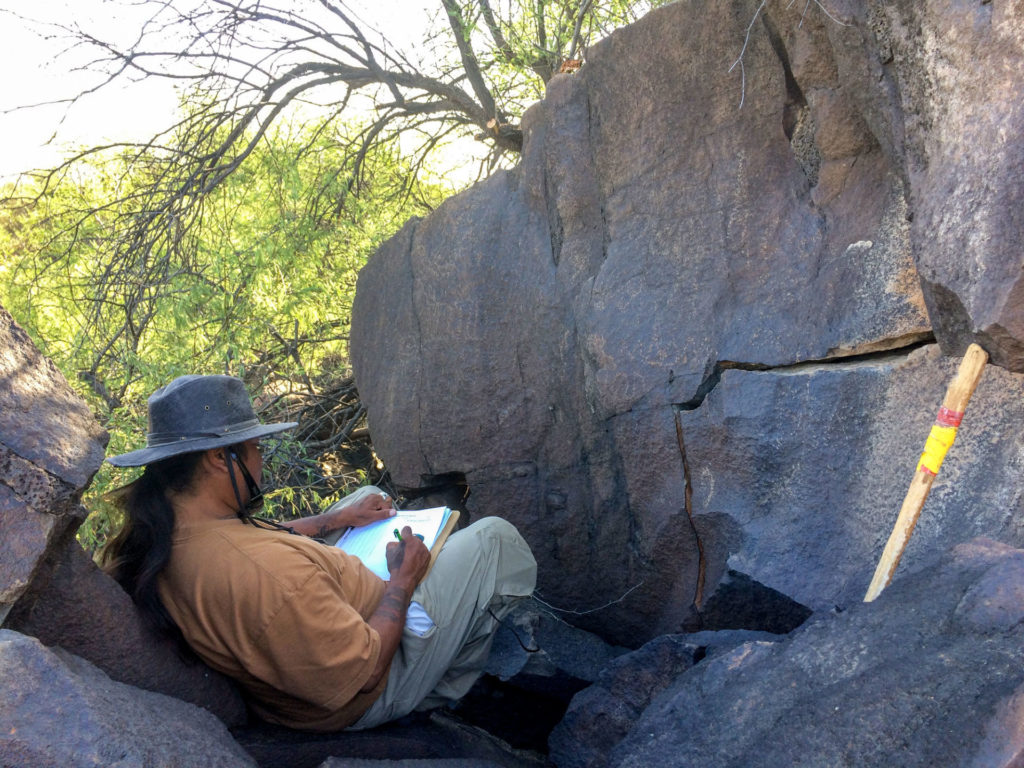

In this fourth and final installment, I talk archaeology with Jason Andrews, a member of the Fort Yuma Quechan Indian Tribe. Jason and I are the same age, and in my earlier life in cultural resource management, I worked on projects in New Mexico in the general area where Jason grew up. So, when we talk archaeology, our conversations are often riddled with nostalgia, as they take us back in time and to much higher ground away from the lower Gila, nearer the river’s headwaters.

As you’ll read, Jason’s life has followed a nonlinear path. He’s tried a lot of things, including a stint in paralegal studies at Phoenix College. Jason is a skilled artist who works with wood and beads and sells his wares at events across southern California. He is also a Bird Singer, which means that families call upon him to help their loved ones pass into the afterlife. He has also become a solid field archaeologist, just like the other LGREAP crew members.

Aaron: What is your first memory or experience with archaeology—with artifacts or ruins, anything like that?

Jason: My first experience with archaeology would have to be as a young child. In the back of my grandma’s house, my grandfather, he was building an underground storage facility. Like a shelter I guess you could say, and as he was digging that out we came across some artifacts…some pottery and some pot shards. And that’s my first recollection of artifacts, really. And ever since then I’ve always gone out behind my grandma’s house and just looked at everything around there, all the pottery. I used to get in trouble for doing so, but I still did it anyway [chuckles]. But yeah, that’s my earliest recollection of artifacts.

Aaron: And where was this?

Jason: I was about five years old, in Ramah, New Mexico. A place called Pine Hill. That’s my family’s land out there.

Aaron: That’s on the Navajo side of your family?

Jason: Yeah, on the Ramah Navajo.

Aaron: What attracted you to the project we’re working on right now?

Jason: Well, actually my sister works for the Quechan language department, and Manfred [Scott, acting chair of the Quechan Cultural Committee] had come in and told her about this program that was going on and she’s known that I’ve always loved being out in the field, hiking, and just out exploring. So, she figured she’d call her older brother up and she did. As soon as I found out about it, I called you up and emailed you and got the process going. It was mainly my sister, with her mouth, and the desire of always wanting to be an archaeologist. I remember…I don’t know if I told you before…but I had an opportunity a long time ago coming out of high school to go to archaeology school, but I didn’t take the opportunity and I kind of kick myself in the butt for not doing so. It just fell in my lap again.

Aaron: How has your perspective on archaeology changed from when you first began the project ‘til now?

Jason: I have a lot more respect for it. I have a lot more respect for what we do and the labor that goes into it. You know, the work hours, the labor, the different strategies and different things we have to overcome to get to data that we need, that you need, and help you out the best we can. It’s…I guess…it’s just being more…learning more is what’s wanting me to also learn more, to pursue this opportunity that I’ve been given.

Aaron: What do find to be the most interesting aspect of this project?

Jason: Oh man, the hiking and the searching. I like the searching part. The not knowing what you’re going to find, and then when you find it, the…the…what can I say…the excitement of it. Being a part of this history that we’re doing out there, and being a part of our ancestors’ history really, and finding out what they did. I like that aspect.

Aaron: So, those days when we do transects for miles and don’t find anything aren’t very exciting?

Jason: Uh, no they’re not, but they come with the job [chuckles]. It’s part of the job so we have to do it. You know, if we didn’t do that then we wouldn’t have found a lot of those geoglyphs and different stuff that we didn’t know was out there. So we see the good that comes out of that transecting stuff [chuckles].

Aaron: How does this project compare with other types of archaeological research you’ve read about or learned about?

Jason: This one for me is hands-on. You can read, and you can gain knowledge through word or by ear, you know, but to be actually part of it is totally different. To be right in there, in the mix, you know. I like that hands-on, just right in there.

Aaron: What do you see the value or the long-term benefit of this project being?

Jason: What we’re doing…the documenting. You said it before, you know, the archaeologists before didn’t really document and leave a fingerprint for us, or footprint for us to really find. So we, ourselves, are out there trying to complete what they started. I think that’s important for the future. We’re going to be able to leave our fingerprint and…um…a petroglyph so to speak…for others to see what we did out there. We’re becoming a part of what our ancestors did. I think that’s very important, leaving our footprint on top of theirs as well…you know…a kind of re-pecking [of petroglyphs] [chuckles]. I like that we’re gathering this information and saving it and documenting, and preserving it for future reference. Like you said, all we had was a dot on a map that said “pot shards here.” What we’re doing is we’re actually documenting everything, and I think it’s really cool.

Aaron: In what ways do you see archaeology contributing to the preservation of Quechan tradition and heritage?

Jason: Archaeology, like I just spoke on, we’re documenting everything we see out there, you know. For me, myself, I’m just now finding out that my ancestral lands, our ancestral lands, actually go way out there where we’re at. You know, I thought we were just stuck in this little dust bowl over here in Yuma, but I’ve come to find out that we’re way over there in Gila Bend area. You know, I think that’s important for tribal members like myself who didn’t know. We’re actually plotting that horizon for those who aren’t really keen on our culture on this side of the [Colorado] river. You know, like with me, I’m pretty well learned in my Navajo side, but my Quechan side I’m still learning. So, being out there is a big learning experience for me, as well.

Aaron: What aspects of Quechan history and tradition are we not accessing through archaeology?

Jason: Hmmm, I would have to say…well, archaeology…in our culture you’re talking about?

Aaron: Yeah, so are there aspects of Quechan history and tradition that archaeology can’t…

Jason: Can’t touch?

Aaron: Yeah.

Jason: Well, there’s our funeral part, you know. We don’t want people digging around our grave sites and such. I guess our tradition is really hidden. Not only in an archaeological sense, but even from a lot of ourselves it’s hidden. I’m trying to touch base on some of that myself [chuckles].

Aaron: How do you think research and the conservation of archaeological materials contributes to the teaching and preservation of traditional Quechan culture and heritage?

Jason: I think, um, what we are learning out there is part of our heritage. We’re actually learning that the battles and the wars that happened out in that area…we’re actually confirming with the artifacts that are being found out there. You know, the stories and the legends that are being told about these battles between the Maricopa [i.e., Piipaash] and the Quechan, and what we’re doing out there is solidifying those legends and those stories. I think that’s very important from an archaeological standpoint for our tribe. We’re putting a seal of approval on it, basically, you know, confirming everything that our elders tell us, these stories. It’s an awesome thing to be part of, to acknowledge and to see. Okay, yeah, these stories our elders are telling us are true, because I’ve seen it.

Aaron: How does Quechan oral history and the archaeology the lower Gila River, which is where we’ve been working, how do they compare? Are they compatible, and if so, in what ways? I think you touched upon that in your previous answer.

Jason: Yeah, they’re definitely compatible. In some ways, like I said, the stories, they’re being confirmed.

Aaron: How well do you think archaeologists and anthropologists, in general, have listened to the concerns and interests of Native communities?

Jason: In past history, not very well. But as of late, you guys are…archaeology is becoming very involved in Native American culture and traditions, which I believe is a great way to start off a relationship with one another, between archaeology and the tribes. We’re working toward the same thing, preserving our traditions, you know. We just preserve it through our stories and songs, and you guys are trying to preserve it through documentation, which is good as well. There are a lot of songs and stories that have been lost due to the fact that we haven’t passed them on. Some stories and some songs that we don’t understand because the elders haven’t told us the stories, but we still sing them. So it’s important that our culture and language include archaeology. They all need to, I think, work together in order for us to move forward. You know, I have a real strong issue with my tribe in how we’re very secretive with the things we do. I don’t think…for me personally, it kind of holds us back from becoming who we really can be. I believe our stories should be shared.

Aaron: Do you believe Native communities should have more of a role in archaeology, and why?

Jason: I believe we should because that’s…I’ve studied, I mean I’ve talked with a lot of people around here on the reservation and they’re like, “why are you learning from a white man your own traditions,” and this and that, and I’m like “well, that’s why I’m out here doing, I’m trying to change that. I’m Native American out here, learning, so I can come back and teach you guys.” So you don’t have that wall, or that barrier, saying just because of the color of our race you can’t be taught this and can’t be taught that. It has to be broken down. For us, as Native Americans, we have to be part of that archaeological aspect because it’s about our people. We need to be able to share scientifically as well as traditionally our culture with others. That’s how I believe. I’m not sure how other people believe, but that’s my aspect. I guess we could grow as a nation if we share a lot more instead of being secretive.

Aaron: Now, you’ve mentioned your Navajo ancestry, and obviously your Quechan ancestry, but you also have O’odham ancestry?

Jason: From Ali Chukson [on the Tohono O’odham reservation], yeah.

Aaron: So, where we’re working, you see archaeologically Hohokam and Patayan mixing, an overlap. Given your unique heritage, and that Patayan is ancestral to Yuman tribes and Hohokam is ancestral to the O’odham tribes, is there anything about what we’re doing that, maybe, speaks to you uniquely or fosters a closer connection to either your Quechan or your Tohono O’odham heritage?

Jason: Well, as a matter of fact, a lot of the designs in the petroglyphs that we’re seeing a lot lately, I see a lot in my Bird [songs], in the singing that I do. As a matter of fact, just this past week I documented a petroglyph of a gourd that was scratched onto the rock. An actual gourd. And I was telling my friend, you know, I was like, “These guys did it way back then. You know, they used those gourds way back then.” This had to be at least the 1800s, because of the scratching, you know, at least the 1800s. So, a couple hundred years of throwing the gourd [gourd “rattles” are integral to Bird Song], and I was just telling her, like, you know, it feels good to be part of that tradition of a Bird singer. It’s continued. It’s survived, and to see that out there on the rocks, and our diamond designs, everything. It’s just beautiful. So that’s what touches me out there, you know, being, seeing those designs and being able to connect with that Bird side and, knowing what it is, it’s…awesome.

Aaron: How would you like to see archaeology carried out in the future?

Jason: I like the way we’re doing it. We’re not touching and we’re not digging. I also like that Lidar stuff [chuckles]. I like that hi-tech stuff. I think we could learn a lot if we dove more into hi-tech, I guess. What’s available to us out there, compared to what was available to the archaeologists back then when they had to dig. Nowadays, we don’t have to dig. You know, we have the radar, the Lidar, all that good stuff. I think it is promising for archaeology in the future to gain more and more knowledge by not even penetrating the earth. You know what I mean?

Aaron: Yeah. So, how has this experience shaped your future goals?

Jason: Oh man, this is…this is…Aaron, this has opened up doors that I’ve been waiting for. You know, I’ve done it all, from automotive, EMT, carpentry, plumbing, a little bit of everything…all kinds of jobs. And out of all those jobs, I’ve never wanted, or waited and yearned to go back to work. I look forward to going back to this. I’ve never had that feeling with any other job. It’s awesome to be able to put my foot in the door in something I’ve always wanted to do. And I know now that it’s going to be something I’m going to continue to do, with the schooling and…it’s something…it’s something I told my mom and my friend here, this is what I am. This is who I am. This is what I want to be. I feel like the Creator put this opportunity before me for a reason, and I can’t just let it slip out of my hands again. Thanks.

Aaron: Yeah. Awesome. Great. So, that’s the end of my questions. Before we go, is there anything that you want to add or any questions for me?

Jason: Um, no. I’d just like to add that, you know, thank you Aaron and Archaeology Southwest for giving us, as a people out here, the opportunity to get to learn this archaeology and be a part of [it], you know, because a lot of us don’t know what goes on as far as the archaeological field and preservation of our culture and our artifacts. There’s only a chosen few out here that do know, and it’s good that a lot of us that are not in that circle now know and are willing to share this knowledge with our people.

Postscript: Since the interview, Jason has enrolled at Arizona Western College in Yuma to further his studies in archaeology. He was also accepted to the 2020 University of Arizona–Archaeology Southwest Preservation Archaeology Field School in Cliff, New Mexico. Although that field school was cancelled as part of the university’s effort to combat the spread of the novel coronavirus, Jason plans to attend the 2021 field school.

As was the case with other LGREAP crew members, Jason’s exposure to “archaeology” happened at an early age, and as part of a family experience. This differs from my first exposure as a child in southeastern Ohio, where I had no idea who made the chips and arrowheads I found in farm fields. To me, archaeology was the making of “otherness,” because the people who left those things behind had been displaced hundreds of years earlier, something my history books didn’t include and something my community couldn’t really acknowledge. What has really come through these interviews is that, for the LGREAP crew, as members of a descendant community, archaeology can be about connection, continuity, and affirmation. It comes down to who’s doing the talking.

This three-year study was awarded a Collaborative Research Grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities (RZ-255760). The NEH is an independent federal agency created in 1965. It is one of the largest funders of humanities programs in the United States and awards grants to top-rated proposals examined by panels of independent, external reviewers. Any views, findings, conclusions, or recommendations expressed in this study do not necessarily represent those of the National Endowment for the Humanities.