- Home

- >

- Preservation Archaeology Blog

- >

- Introducing cyberSW 1.0

Jeff Clark, Archaeology Southwest

Barbara Mills, University of Arizona

Matt Peeples, Arizona State University

Scott Ortman, University of Colorado Boulder

Sudha Ram, University of Arizona

(June 10, 2020)—After some COVID-related delays, including the stranding of a key programmer in Wuhan, we are pleased to officially launch the cyberSW knowledge discovery system (www.cybersw.org).

CyberSW is a collaborative online software platform with tools for searching, exploring, and analyzing the pre-Hispanic archaeological record of the U.S. Southwest and Northwest Mexico. Stimulating research and dialogue among archaeologists, scholars from other disciplines, tribal members, land managers from various government agencies, and the interested public is the project’s key goal.

Protecting archaeological sites on the land is a core commitment. That is why you will read, right up front, at the top of the page where you begin to explore, “Precise site locations have been masked for their protection.” Let us be clear: These sites are not exactly where our maps display them.

What Is cyberSW?

Built on an innovative, flexible Neo4j graph database platform, CyberSW 1.0 is a powerful system for reconstructing demography—population size, density, distribution, and structure. It also enables exploration and analysis of important patterns in the past across the U.S. Southwest and Northwest Mexico. Such patterns currently include the distributions of chronologically and regionally distinctive pottery, forms of public architecture, and obsidian, a volcanic glass that can be geochemically traced to its source.

At present, data in cyberSW are primarily from residential sites that date to 1200–1450 CE, known generally as the late pre-Hispanic period. For sites in the Chaco World, the database includes information going back to 800 CE, with an emphasis on great houses and public architecture. We are in the process of expanding the data repository to include earlier time periods in other regions, especially the Hohokam archaeological culture region of present-day southern Arizona and northern Sonora, Mexico. For example, we recently added data about ballcourts, public architecture known from Hohokam archaeology. Citizen scientist Katherine Cerino has spent almost two years entering feature-level ceramic and architectural data from intensively excavated Hohokam ballcourt sites.

Our ultimate plan for cyberSW is to include all pre-Hispanic archaeological and environmental data at maximum spatial resolution, down to individual features and strata within them. This would bring in faunal and botanical remains, stone tools, rare or exotic objects, and rock art. This is one reason we chose the Neo4j graph database platform—because it readily accommodates new classes of data and analyses. In fact, the possibilities are infinite with this structure, and we hope users will offer suggestions for good additions.

Importantly, cyberSW contains an integrated living data repository managed by fulltime database manager Josh Watts and developer Andre Takagi. These two stewards will ensure that cyberSW is continually updated, revised, and expanded.

For more on the project’s history, content, significance, and future, read “Tell Me More” below.

How Does It Work?

CyberSW is not a digital archive or a virtual library. You don’t have to pour through hundreds of reports and manuscripts for data or develop standardized schemes. Through the generous support of the National Science Foundation (NSF), project archaeologists have spent the past 20 years compiling these data for you and creating data dictionaries that new project results can be built upon.

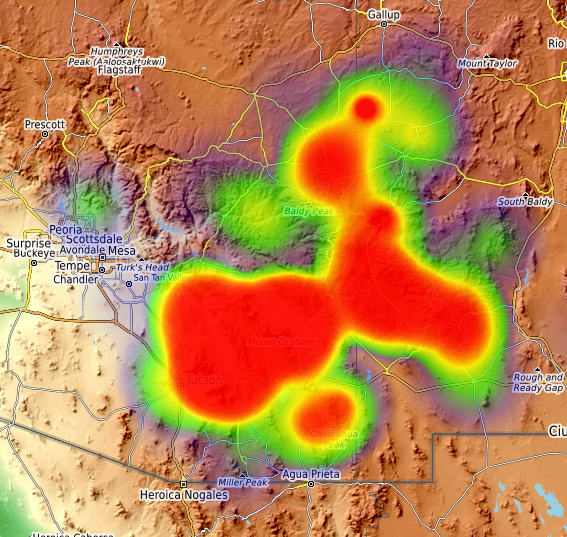

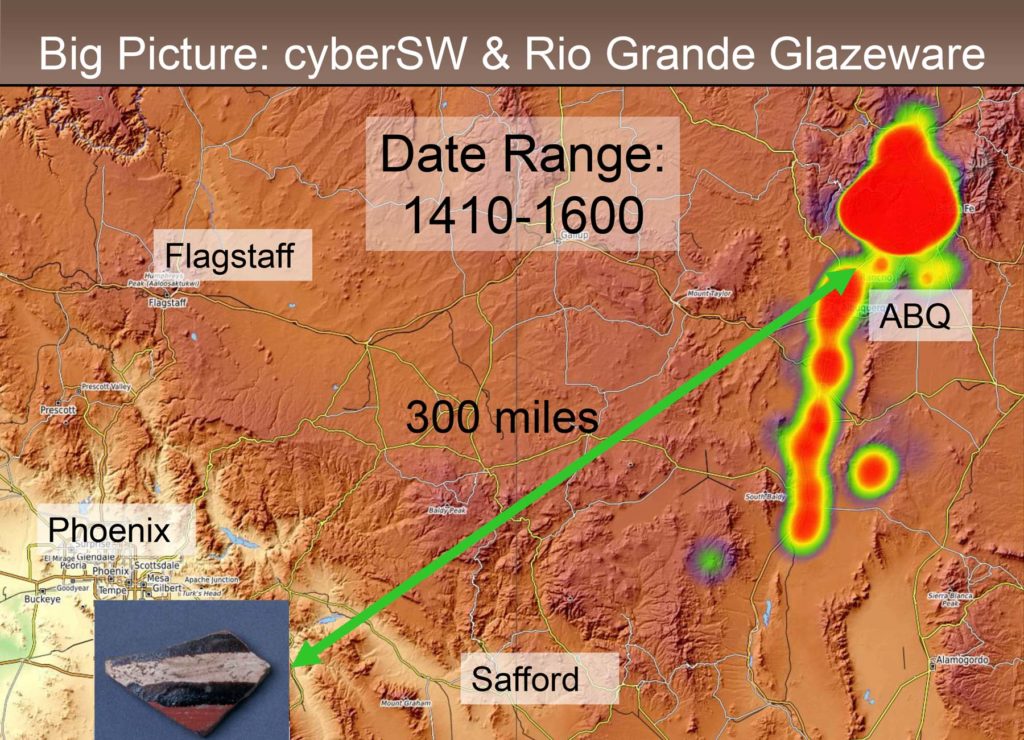

Users can choose a ceramic ware/type, obsidian source, and/or public architecture feature, and the data will be displayed in the format you have selected. Formats include site distributions and heat maps (similar to the all-too-familiar Johns Hopkins COVID site) that may be downloaded as publishable figures, and aggregated tables that may be downloaded as various file types for further analysis.

We are continuing to expand an analytical toolkit that includes a powerful chronological tool developed by Scott Ortman (University of Colorado Boulder) for consistently estimating site occupation dates from ceramic production date ranges. This tool dates sites and site groupings. In addition, you can conduct your own analyses in cyberSW’s personal virtual workspaces. You can also readily obtain the sources of data and download the associated data tables, along with bibliographic information on data sources.

Now What?

Go check it out! Help us make cyberSW even better and more useful.

We strongly encourage users to provide constructive and succinct comments, as well as suggestions on what you would like to see in future versions of cyberSW, to database manager Josh Watts (jwatts@archaeologysouthwest.org).

We think the farther you delve, the more you will find.

Tell Me More

CyberSW integrates data generated by archaeologists working in the U.S. Southwest and Mexican Northwest over the past 150 years, including Cultural Resource Management (CRM) projects on which billions of taxpayer dollars have been spent. The database underlying cyberSW is large and complex, the product of combining synthetic databases from projects funded by NSF projects over the past two decades, including the Coalescent Communities Project (Archaeology Southwest [ASW], Museum of Northern Arizona, Western Mapping, Inc.), Southwest Social Networks Project (ASW and University of Arizona [UA]), Chaco Social Networks Project (ASW, UA, Arizona State University [ASU]), Village Ecodynamics Project (Washington State University, Crow Canyon Archaeological Center), and finally cyberSW (ASW, UA, ASU, and University of Colorado Boulder). University of Arizona–Archaeology Southwest projects have focused on reconstructing ancient social networks through time (see, for example, Archaeology Southwest Magazine Vol. 27, No. 2 and Vol. 32, Nos. 2 and 3). The regional databases generated by these projects have much broader applications, however.

These projects scoured the existing academic and CRM literature in various regions, tracked down obscure and unpublished manuscripts, visited numerous repositories to examine thousands of site cards, interviewed regional experts, and conducted new research to fill data gap areas. The latter efforts include analyzing and inventorying the extensive Robinson Collection from the poorly documented Safford Basin. Led by Jaye Smith, this multiyear citizen science project involves more than 30 volunteers. We envision more citizen science projects like this in the future that will help cyberSW grow.

At this juncture, the cyberSW repository contains information on more than 25,000 pre-Hispanic settlements. Data have been compiled and systematized on more than 13.7 million ceramics from more than 120 wares and 800 types that are linked to nearly 9,000 type name/spelling variants. In addition, more than 10,000 geochemically sourced obsidian artifacts from 73 obsidian sources are in the database. Finally, information on hundreds of public architecture features are in cyberSW, including great houses, great kivas, platform mounds, and ballcourts.

CyberSW provides integrated access to the largest (to our knowledge) archaeological research data repository in the U.S. Southwest and northwest Mexico. After a simple registration process, it is available free of charge to any researcher, citizen scientist, tribal member, land manager/owner, or other individual interested in regional archaeology—with the caveat that site locations have been geo-masked to prevent misuse. The effort saved in compiling and standardizing ceramic, obsidian, and public architecture data should revolutionize and stimulate archaeological research, as well as facilitate interdisciplinary research.

Although there is still plenty of room for expansion and revision, cyberSW 1.0 provides a strong foundation for future generations of archaeologists to conduct synthetic research with a strong empirical grounding. The incalculable amount time spent “reinventing the wheel” by individual researchers compiling and systematizing similar or overlapping data sets can now be redirected toward more productive research pursuits. Projects that use the standardized typologies developed for cyberSW can be easily added to the data repository, breaking down project-specific silo walls that are a huge obstacle in our discipline.

2 thoughts on “Introducing cyberSW 1.0”

Comments are closed.

CyberSW will be a great help for the REA Rapid Ethnographic Assessment Projects that we do for different projects on our Pueblo.

Directed here for volunteer opportunities. Retired PH.D. with skill in statistics. I read Spanish.