- Home

- >

- Preservation Archaeology Blog

- >

- An Introduction to the Study of Ancient Ground Sto...

Tessa Branyan, Desert Archaeology, Inc.

(July 30, 2020)—In archaeology, we classify many stone tools that we find as “ground stone” objects. Ground stone objects can be almost any stone or mineral—flaked stone not included—that has experienced some kind of human intervention. This may sound like a pretty broad definition, but that is intentional. Ground stone objects are organized into two groups: artifacts and ecofacts.

Ground stone artifacts are objects that people modified from their natural state through manufacturing or use, or both. This includes modified tools, ritual objects, and personal items, such as ornaments.

Ground stone ecofacts are unmodified objects that people picked up and carried into an archaeological site, possibly for a specific use, for future use, or for their unusual appearance. This is the “human intervention” mentioned in the definition above. Although ecofacts have no signs of use and were not physically modified in any way, they do not naturally occur in or in large amounts in the soil around the site, and potentially originate from material sources from several to hundreds of miles away.

The presence of these ecofacts in archaeological sites miles away from their original sources means someone had to purposefully bring these objects to the sites. Ground stone ecofacts include things such as raw earthy hematite, raw turquoise, quartz crystals, petrified wood, and other natural items.

Why do we study ground stone artifacts and ecofacts? The simple answer is that they can tell us a lot about the past. Ground stone can help us answer all sorts of questions about life in the past, including subsistence and agriculture, trade, population movement, craft production, and technology.

But, really, how can these seemingly simple rocks tell anything about the past? Through scientific analysis! Analysis of ground stone artifacts and ecofacts helps us extract the answers to our questions, and so much more. Ground stone analysis is a multifaceted method that involves an interesting combination of behavioral and technological approaches, ethnographic analogy, cross-cultural comparison, previous archaeological research reviews, and experimentation.

We also use traditional descriptive techniques (weighing, measuring, visual description, etc.) in conjunction with macroscopic and microscopic techniques to identify the objects and determine what activity or activities they were used in. This approach emphasizes the idea that ground stone objects have a life-history and that they are physical representations of past human activity, which not only helps us better understand the ground stone objects we study, but also helps us humanize and individualize the past.

It may be difficult to visualize the life-history of a rock, but it is essential to the behavioral approach in which our analytical methods are situated. The life-history of a stone begins the moment a stone is picked up, and does not end until the object is discarded in the archaeological record, where we find it. We document this life-history by evaluating several variables:

- Stone Selection and Procurement: the type of material the object is made of, the characteristics of that material, and where that material can be found

- Design and Manufacture: the modifications made to an artifact that alter the artifact from its natural state and the methods used to make these modifications

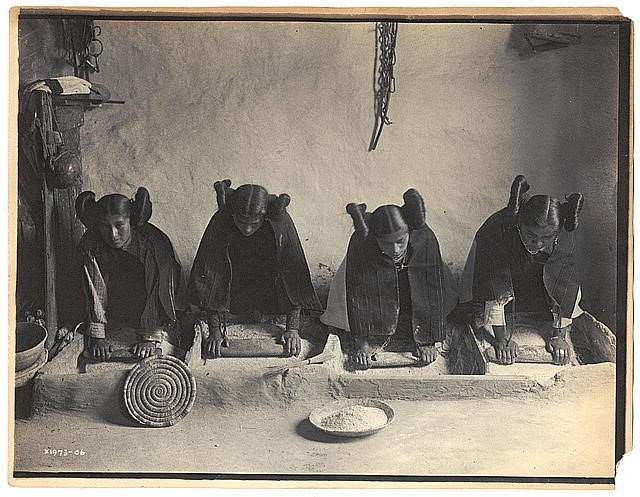

- Use Wear: the type of wear and degree to which a tool was used; wear is defined as the progressive reduction of a stone’s surface, resulting from the relative motion between the tool and a contact surface during an activity (for example, the striations and grain alterations made by a mano used to grind corn on a metate)

- Tool Use: the number and different types of tasks in which a single tool or object was used

- Sequence: the order in which the different activities identified on a single tool occurred

Although we do measure, weigh, classify, and photograph the objects just as in any normal scientific analysis, this life-history model we use to analyze ground stone is the essential building block to interpreting the past. The variables we evaluate during our analyses are designed to provide a framework that we can use to answer the specific questions we have about the person or people who once collected, made, or used the object.

For example, the information we record while evaluating the object’s material gets us thinking about how far a person was willing to go for a specific rock type, what material/sources they might have favored, where this person might have come from, and with whom they might have interacted to obtain what they needed—which can potentially tell us a lot about material accessibility, trade, craft specialization, and migration. Design and manufacture can help us understand the needs and skill of the person who made the tool, whereas use-wear and tool use can tell us what activities the person undertook, what their tool-use habits were, and even what their dominant hand might have been.

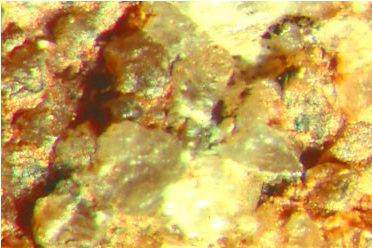

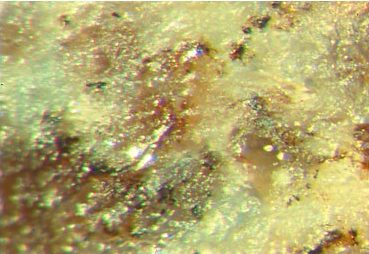

Use-wear is probably the most important of these five life-history variables, because it is use-wear patterns that often tell us specifically how the tool was used. When a ground stone tool is used against another surface, like using a mano to grind corn against a metate, the tops of the individual grains that make up the surface of the tool are physically altered.

But how these grains are altered depends on several factors: the texture, hardness, and durability of both the tool and the contact surface, the presence of an intermediate material (like the corn between the mano and metate), and the length of tool use. These factors dictate how the artifact’s grains change—whether they are crushed, fractured, flattened, rounded, or polished, among other possibilities. These changes can be compared to the natural surface of the stone under a microscope and helps us determine, based on the wear patterns we see, whether the tool was used to work shell, stone, wood, or pottery, for example.

When combined, the different elements of ground stone analysis—the technical analysis itself, alongside ethnographic analogy, experimentation, cross-cultural comparison, and previous archaeological research reviews—help us reconstruct past behavior and better understand the people who once used these tools at an individual level.

Additional resources on ground stone artifacts and ground stone analysis:

Books:

Ground Stone Analysis: A Technological Approach, Second Edition, Jenny L. Adams (2014), University of Utah Press.

The Life-Giving Stone: Ethnoarchaeology of Maya Metates, Michael T. Searcy (2011), University of Arizona Press.

Posts at Field Journal, the blog of Desert Archeology, Inc.:

The Tell-tale Art: Recognizing Use-wear on Stone Tools, Jenny L. Adams (2017), www.desert.com/use-wear/

It Takes Both: Identifying Mano and Metate Types, Jenny L. Adams (2017), www.desert.com/mano-metate/

Peer-reviewed journal articles:

“Experimental Replication of the Use of Ground Stone Tools,” Jenny L. Adams (1989) in Kiva 54:261–272.

“Bringing Stones Tools to Life: The People behind the Rock,” Jenny L. Adams (1996), in Archaeology in Tucson 10(4):1–5.

“An Ethnoarchaeological Perspective on Ground Stone Production at the Santiago Quarry in the Casas Grandes Region of Chihuahua, Mexico,” Michael T. Searcy and Todd Pitezel (2018) in Latin American Antiquity, 29(1): 169–184.