- Home

- >

- Preservation Archaeology Blog

- >

- Societal Change in the Past

(August 18, 2020)—There is no question that these are exceptional times.

We are living not only through the “new norm,” but also through the shattering of established norms. As the not-so-distant past demonstrates, previous generations also faced exceptionally challenging times –disenfranchisement of African Americans and other minorities during the 1890s, the 1918 influenza pandemic, and Japanese American internment and the Zoot Suit Riots during the Second World War, among others. And this has happened throughout history. In this post, we’ll look at an example of societal change from my research.

“Failure” and Its Aftermath

Over the past few months, I’ve been noticing various analysts and commentators claim that the United States is a failed state, or is on its way to becoming a failed state. For example, in the June 2020 edition of The Atlantic, George Packer wrote, “Every morning in the endless month of March, Americans woke up to find themselves citizens of a failed state. With no national plan—no coherent instructions at all—families, schools, and offices were left to decide on their own whether to shut down and take shelter.” Packer was addressing the fact that the failures of the federal pandemic response highlight larger-scale problems with the administration, but his analysis has wider implications.

As an archaeologist, I find this alarm-sounding interesting. Pause for a moment and ask yourself what the word “state” means. Is it, as Dictionary.com defines it, “a politically unified people occupying a definite territory; nation”? Is it Big Brother of George Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four? Is it something in between? Or is it the social norms that structure our lives?

I believe that the “state” Packer and others, such as anthropologist Wade Davis (Rolling Stone August 6, 2020), are talking about is that last option. Social norms—the shared values about what is expected, permitted, or forbidden—are being challenged and rewritten. What will happen to us and our culture if our state completely fails? That is the fear implicit in these recent alarms.

Lessons from the Polvorón Phase

In fact, the past often shows us possible outcomes. In the 1400s, the Hohokam World began to change dramatically. Farmers along the lower Salt River, the area I studied for my dissertation research, were experiencing unprecedented change. Significantly, communities were abandoning platform mounds and apparently rejecting the ideology associated with them, at the same time multivillage irrigation communities were declining and collapsing.

This society was not a state, and archaeologists have debated the use of that term for preindustrial societies, but this era—the end of the late Classic period, circa 1300–1450—may be thought of as a time when a cultural identity ceased and a new one came into being. The end of Hohokam as an archaeological culture was not the end of a people, however. The children of the collapse of the Hohokam World appear to have taken on a different identity, though we are still trying to understand this archaeologically.

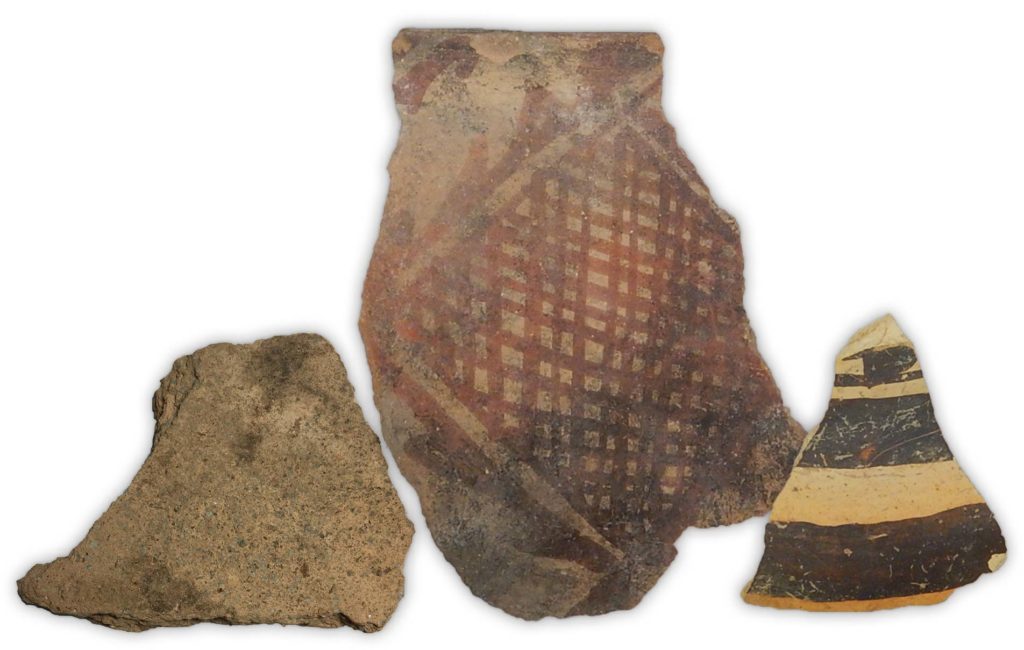

In the post-Classic period, known as the Polvorón phase, people did maintain connections with some Hohokam traditions: they continued using a certain kind of decorated pottery archaeologists call Salado polychrome; they continued using obsidian from sources in southern Arizona for certain tools; they practiced irrigated agriculture, although on a much reduced scale; and they maintained relationships with groups to the west and elsewhere.

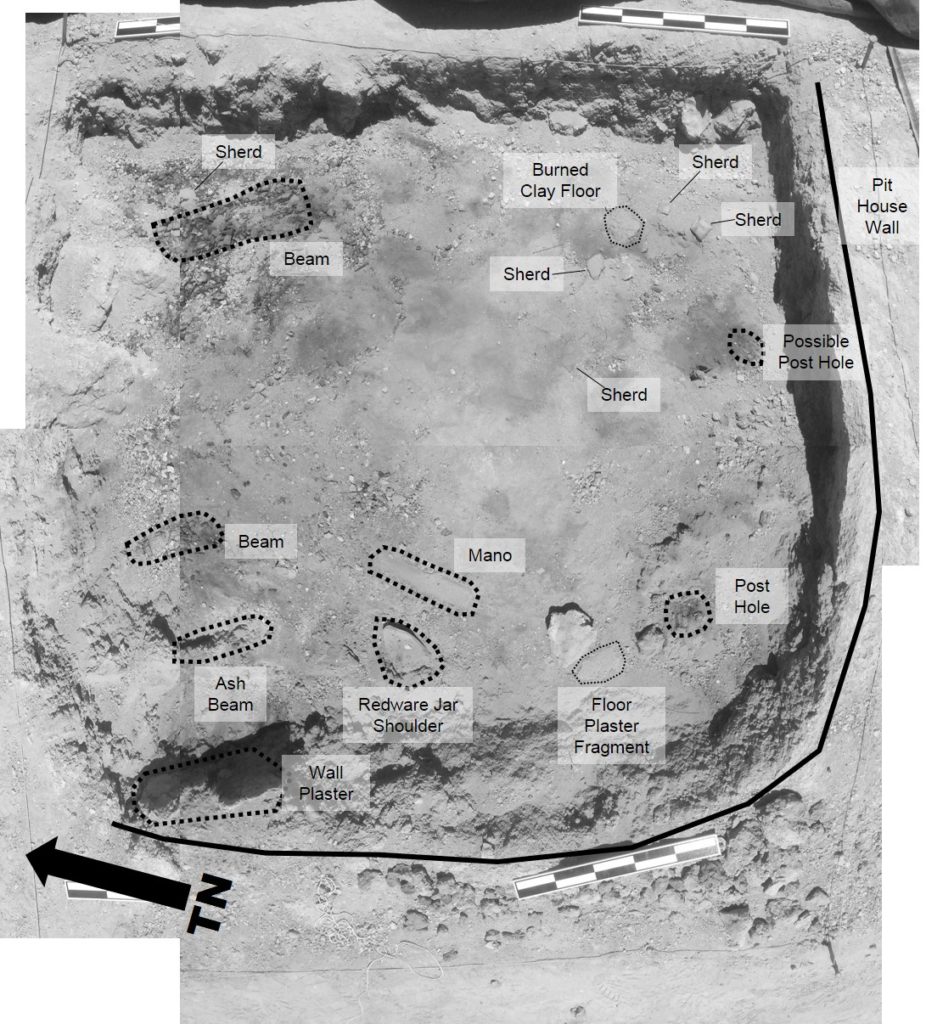

Yet we also see that people began dwelling in jacal (wattle and daub) pithouses again, as they had centuries earlier, even cutting these into the adobe compounds and platform mounds built by their more immediate forebears. They appear to have eaten differently, too. Compared to the late Classic period, it seems that wild plants might have constituted a much greater proportion of the diet—but much more research is needed to establish this.

This was not merely a replacement of some cultural ideas, but actually a profound rearrangement of preexisting traits into a new lifestyle. What other evidence indicates how fundamentally things changed?

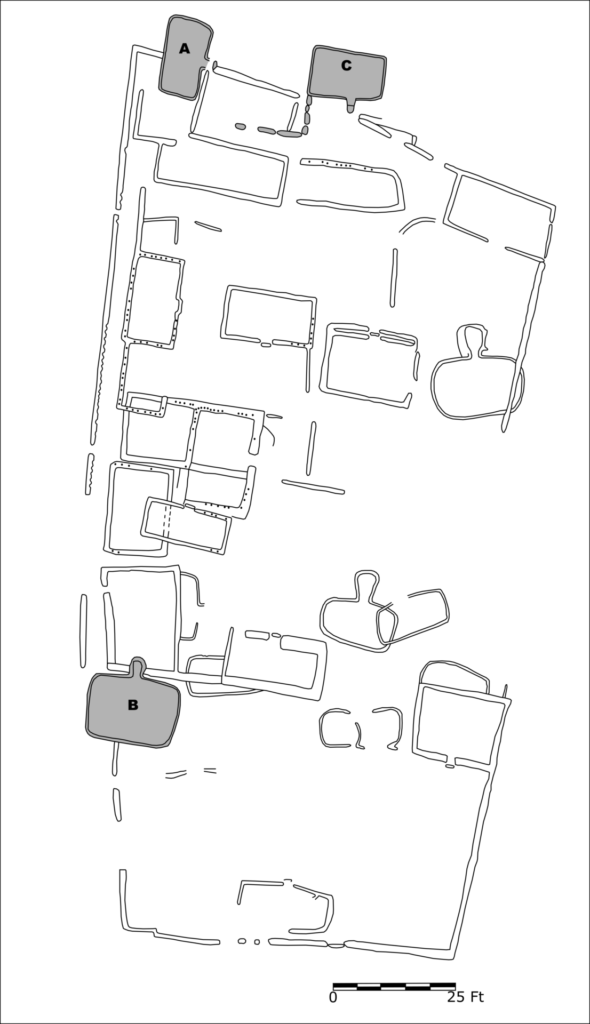

First, although Classic period adobe compound rooms look different from pre-Classic pithouses, the compounds themselves maintained a spatial arrangement similar to earlier pithouse-courtyard household groups, albeit behind walls. This essential household residential footprint did not carry into the post-Classic. Polvorón phase sites do not appear to be as structured as Hohokam farmsteads and larger settlements were. Instead, they appear to be loosely organized and without a clear site plan; they look more like fieldhouse sites.

Second, during the late pre-Classic through Classic, circa 1070 to 1300, tens to hundreds of people lived in aggregated hamlets and larger villages. During the Polvorón phase, however, people lived in low-density settlements that were widely distributed across the lower Salt River and elsewhere in the Phoenix Basin. Residents of these settlements, which probably comprised no more than a family or two, tended agricultural fields near the lower Salt and the middle Gila Rivers and along intermittent water sources such as Queen Creek.

Persistence

So, what does life during the Polvorón phase have to do with our current situation and alarms about a failed state? Those people were, after all, living in very different conditions than our current society—how many people do you know who are solely dependent on the food they grow and collect? Nevertheless, the farmers living along the lower Salt River during this transition experienced not only the erosion of established social norms and cultural identities, but also the replacement of those norms and identities with new ones.

What was it like to live through that? To be a farm family watching society crumble around us while we try to get by, or even survive? Michelle Hegmon and others have attempted to elicit people’s lived experience through an approach known as Archaeology of the Human Experience, which includes several avenues of research—bioarchaeological examination of injuries, for example. Unfortunately, the the Polvorón archaeological record is too ephemeral to attempt this approach.

If this example from the past provides any insight into our current situation, it is that the loss or rejection of deep-rooted social norms and cultural identities is not the end of the story. As Akimel O’Odham traditional history says, when Elder Brother and O’Odham ancestors overthrew the sivanyi living at the platform mounds at the end of the Classic period, their actions allowed a different way of life to emerge. There will be significant changes during a profound event like the failure of a state—some surely very painful, some rending the very fabric of cultural identity—but people will persist.

Chris Caseldine writes about the Polvorón phase in the new issue of Archaeology Southwest Magazine, “The Casa Grande Community.” Learn more here.

3 thoughts on “Societal Change in the Past”

Comments are closed.

I don’t see how this transition cannot be defined as the collapse of a state, with resulting disintegration of conditions. A state is not simply a collection of norms or people getting along together. It requires authority. As a single example, the engineers who built the massive Hohokam irrigation system had to be people of enormous stature and authority. When that state collapsed a complex urban life disintegrated into isolated pit houses, with I assume, great loss of capacity to maintain food supplies for many. It is comforting to think every subsequent social organization after social disintegration is equally good but would we think so if our state were to collapse?

This reminds me of my high school English class where we compared everything to a chair. Life is like a chair because…..A, Life is like a chair because….B. The author is to be commended for their imagination and confirmation bias skills..

Excellent analysis of material remnants. Have you worked with folks who descend from peoples of the Hohokam World? Presumably your analysis would be enhanced with memories, stories, values, norms identified by them.