- Home

- >

- Preservation Archaeology Blog

- >

- Understanding Mimbres Painted Pottery

This guest post summarizes a new article by Michelle Hegmon, Will Russell, Kendall Baller, Matthew Peeples, and Sarah Striker, “The Social Significance of Mimbres Pottery,” which will appear soon in American Antiquity (DOI: https://doi.org/10.1017/aaq.2020.63). This is one of the first publications to use cyberSW, and we’re pretty excited about it! For more information about the article, contact Karen Schollmeyer at karen@archaeologysouthwest.org.

Michelle Hegmon, Arizona State University, and Will G. Russell, Logan Simpson

(September 19, 2020)—You’ve seen the designs, if not the pottery itself. T-shirts, coffee mugs, pot holders, and more are decorated with motifs from Mimbres pottery. They burst onto the scene over a millennium ago in what is now southwestern New Mexico. But by about 1030 CE things changed. People left their large villages and adopted new ways of life. How can we understand this—the development of this spectacular pottery, and then the sudden changes?

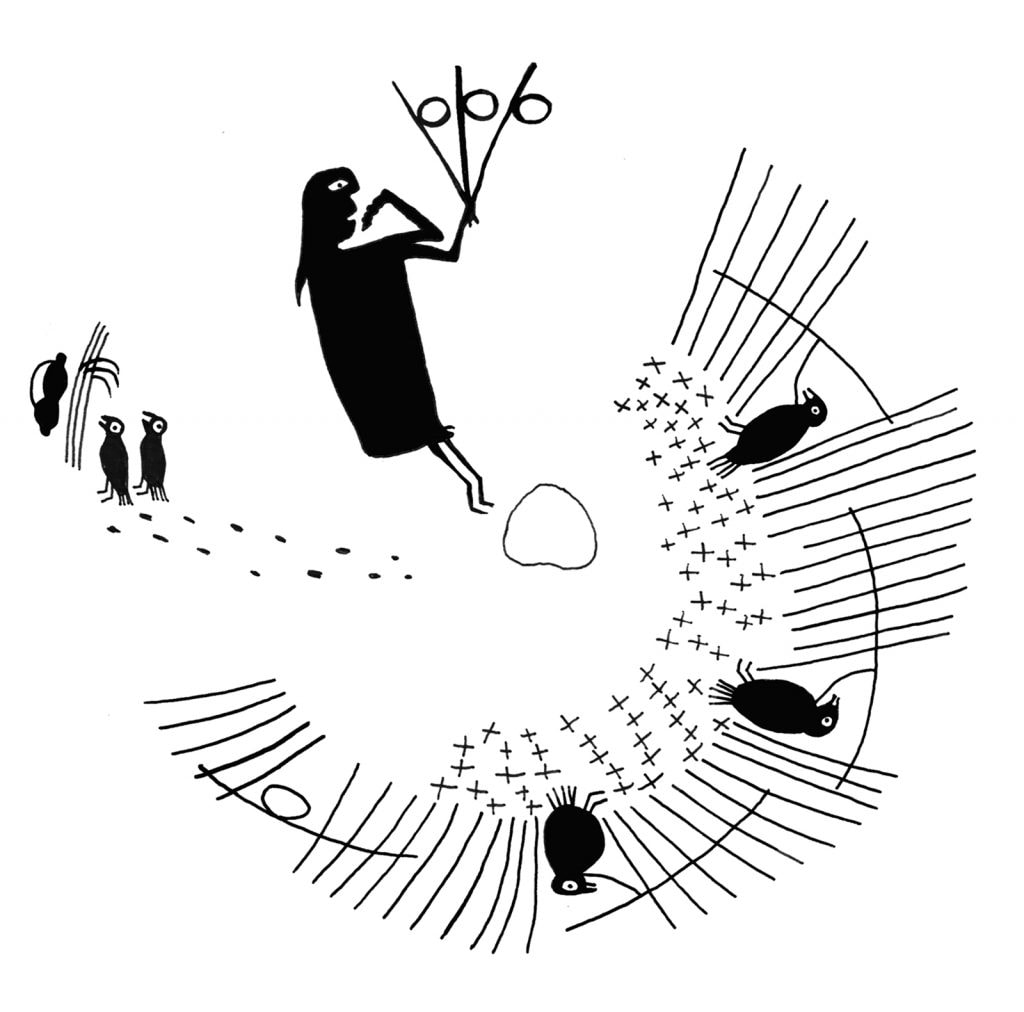

Archaeologists know a lot about what was painted on the pottery: realistic animals, mythological creatures, and scenes from stories. But we know very little about the social significance of these clay vessels and the roles they played in people’s lives. We’ve also shied from the intriguing but difficult question, “Why is it so beautiful?”

Stepping in what we hope is the right direction, we worked with Kendall Baller, Matt Peeples, and Sarah Striker to take a synthetic look at the pottery by drawing together old studies and new approaches. We just published our findings in American Antiquity.

There has been a sense among archaeologists that the Mimbres region was delineated by some kind of boundaries. Now, with data from cyberSW, we can test that idea systematically. We can show that Classic Mimbres sites have almost all Mimbres pottery, whereas non-Mimbres sites have next to none. In other parts of the Southwest, pottery styles gradually taper off—this kind of all-or-nothing distribution is rare.

Mimbres designs have been analyzed before. We have searched for easily recognizable patterns: rabbits here, mountain sheep there. But no matter what we looked at—species, animal habitat, design embellishments—we could not discern any patterns in how designs were distributed. The pottery was made by specialists throughout the region and then distributed across the region so that everyone had the same designs.

Some artists developed distinctive styles we can recognize today. One example is the creation of “negative” images by painting a black background from which white rabbits emerged. Individual styles are also very unusual in the Southwest.

By pulling these threads together and weaving them into other elements of Mimbres archaeology, we’ve been able to better understand, we think, how this pottery fit into Mimbres society. Parts of the Mimbres region were especially good for farming, but this arable land was limited and in high demand. Families that controlled good farmland developed a land tenure system that helped them keep what they had and pass it along to their children. Ancestral claims to farmland were justified and marked with burials, and these often included beautiful vessels. As this tradition developed, potters and painters were encouraged to develop their art.

We think the message shared and communicated by this remarkable pottery was essentially “I belong here.” Vessels were used by long-time residents and new migrants alike, but if someone left the region, the pottery and imagery stayed behind. Mimbres pottery and the messages it conveyed helped bind people with place: “I accept the Mimbres way of life, and you accept me into it. Individually, we are parts of it. Together, we are it.”

2 thoughts on “Understanding Mimbres Painted Pottery”

Comments are closed.

Explore the News

Related to This

-

Project cyberSW

I don’t agree with the notion that the pottery and imagery stayed behind. Take a look at the amount of Mimbres pottery in Dona Ana sites, and Mimbres pottery occurs as far east as the Guadalupe Mountains in Texas, especially around the salt lake on the west side of the range. I attribute the distribution of Mimbres pottery outside of the core area as a product of gifting in association with valley feasts and other events.

As an artist and archaeologist I am inclined to think that too little credit is given to the idea that the designs on Mimbres pots are simply expressions of creativity, perhaps driven by the same competitive urges I witnessed at Acoma Pueblo one summer. Archaeologists are so eager to squeeze sociology out of their artifacts that they offer “just so” stories as if they were fact. Plausibility is not demonstration.