- Home

- >

- Preservation Archaeology Blog

- >

- A Resource for Zooarchaeology and Conservation Bio...

(September 29, 2020)—I’m happy to share news of a new publication some of you may be interested in. Wildlife biologist Stephen MacDonald and I just published Faunal Remains from Archaeology Sites in Southwestern New Mexico, an occasional paper of the Museum of Southwestern Biology, and it’s now available as a free download from their website (https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/occasionalpapers/).

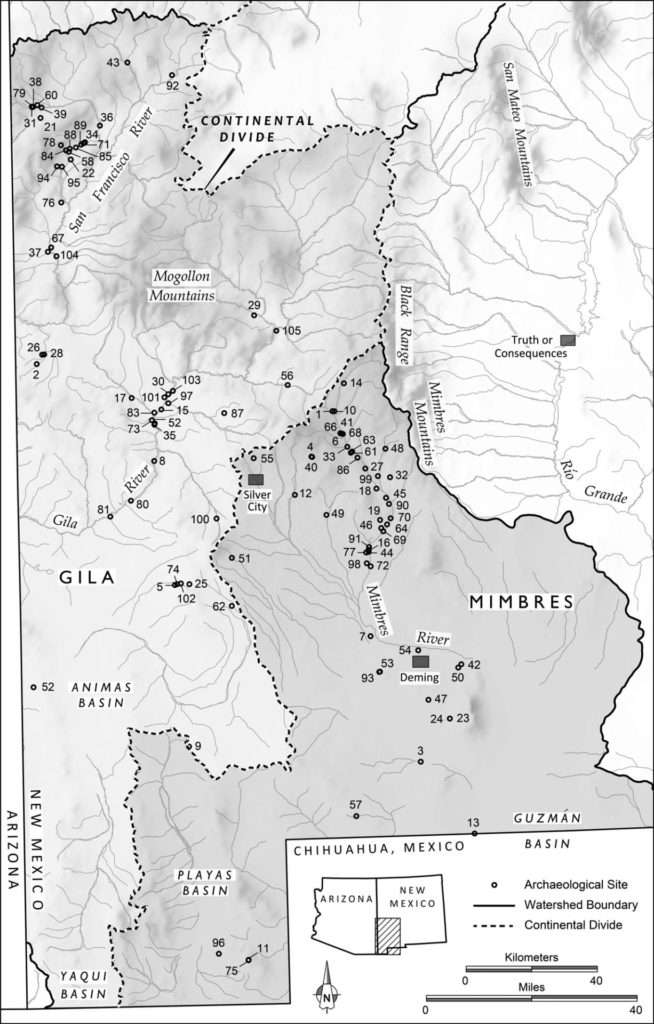

This paper brings together a list of animal species found at 105 archaeological sites in the Mimbres and Upper Gila drainages in southwest New Mexico. This is the first time this information will be all in one place, accessible to biologists, archaeologists, and anyone interested in animal species distributions and how they have changed over time.

Getting to work with Steve was a happy accident. He lives in Gila, New Mexico, near the location of our annual Preservation Archaeology Field School. When we first met a few years ago, we started talking excitedly about the past and present ranges of species like muskrats and beaver and why those have changed. As a zooarchaeologist, I’ve long been interested in ways we can make archaeological data on animals relevant to today’s conservation biology issues. Our conversations led us to realize that it would be very useful to create a reference biologists could use to easily determine where animal species have been found in archaeological sites (and then find the original reports on those remains).

Talking with Steve also made me realize how slowly new information from conservation biology on topics such as mammal distribution or changes in scientific taxonomy gets incorporated into the archaeological literature. Having a convenient place to look up what species have been found in southwestern New Mexico archaeological sites will help zooarchaeologists realize when an animal we’ve identified is an unusual occurrence. That means we can better discuss the identification and its implications in our reports and articles.

Fortunately, the ideas Steve and I were discussing meshed well with another project paleoethnobotanist Michael Diehl and I were working on—collecting and analyzing data from preexisting archaeological projects in the Mimbres Mogollon region (NSF BCS-1524079). Mike and I were busy tracking down documents like unpublished site reports and Master’s theses from decades past and working with collections from older archaeological projects whose budgets hadn’t included analysis of plant and animal remains. Archaeology Southwest volunteer Jaye Smith also spent many hours putting information from old paper files from the Mimbres Foundation’s 1970s excavations into digital form. Thanks to these efforts, Steve and I were able to pull together a large amount of information on animal remains from this region.

One of the most challenging aspects of this paper was investigating reports of species that we were surprised to find in the Upper Gila and Mimbres watersheds. Some of these unusual occurrences should be reexamined by specialists to confirm these decades-old identifications, an effort we hope will be made easier by a table in our paper that lists the repositories where all the archaeological collections are curated.

Other surprising identifications change our understanding of the past distributions of animals, such as yellow-faced pocket gophers (Cratogeomys castanops), which today are not found west of the Rio Grande but extended farther west in the past. Just as interesting are species that seem to be missing from the archaeological record. For example, beavers (Castor canadensis) are reported in archaeological sites from the Upper Gila, but there are no confirmed occurrences of their remains in archaeological sites in the Mimbres watershed. They are, however, present there today, and how they got there is an interesting question for future research. Understanding the historic distributions of different animals and how and why those have changed over time has important implications for how animal populations and habitats are managed today and into the future.

We hope this paper is useful for people in many different fields of study who have questions about where animal species were found in the past. The summary information we’ve collected will lead you to the original reports and allow you to pursue all sorts of questions, including those raised here—and many more we have not thought of.

Thank you to Jaye Smith and to the National Science Foundation (NSF BCS-1524079). Funding from the NSF, National Endowment for the Humanities, and similar American institutions is essential to scientific research, funding investigations that lead to new and interesting insights and collaborations that weren’t on scientists’ radar when they initially proposed their research.