- Home

- >

- Preservation Archaeology Blog

- >

- Following in Their Footsteps

(November 12, 2020)—One aspect of ancient life in the Southwest that doesn’t get its fair share of attention is that people really got around. Movement was a regular part of life. Such is the case with the contemporary world, as well, in which people regularly zip hundreds of miles in a matter of hours on freeways. But in the past, before cars, wagons, and horses, people still traveled vast distances; the difference is that they did so by foot.

Examples of this are abundant and varied. One is the early-nineteenth-century migration of the Xalychidom and allied Kohuana and Halyikwamai communities from the lower Colorado River valley to the middle Gila River valley. Some of them traveled even farther to northern Sonora before ultimately joining their allies along the Gila. Other examples are the O’Odham salt pilgrimages to the Gulf of California. Those journeys would take anywhere from 4 to 12 days roundtrip, depending on which village one started from.

I imagine walking to the Gulf from my home in Tucson would be challenging. Coupling that distance with the Papaguería’s unforgiving climate and terrain takes the challenge to a totally different level. I think I could do it, as long as I knew which way to go, where to get water, where I could sleep safely, and where I might encounter friends and foes along the way. In other words, I’d need a contingency plan. Some company would help, too. I am in awe of the physical and spiritual endurance of the O’Odham pilgrims who made that journey.

Because most archaeologists working in the Southwest focus much of their time and energy on residential settings—for various reasons I won’t get into here—the spaces in between are often overlooked and underappreciated. Certainly, the archaeological landscape between such centers of past life is comparatively thin…a few pottery pieces here, some petroglyphs there, and maybe a projectile point lost during a hunt long, long ago. It can seem underwhelming to some. But this is the space through which people traveled to get from A to B. Unlike today, they couldn’t fly over it or drive by it. They instead had to walk it, and by walking it they had to experience it in way we don’t have to today.

In most places, studying how people moved about the landscape is a largely conjectural enterprise because footpaths don’t preserve well, except in very specific environmental contexts. The desert pavements in the southern Southwest are one such context, and for this reason we can still see, map, and study sections of Indigenous trails even though they haven’t been used for centuries. Ancient trails were actually one of Malcolm Rogers’s (1890–1960) main research enterprises. He mapped trail corridors stretching from the Peninsular Ranges outside of San Diego to Phoenix’s West Valley. Such routes must have been used to move shell from the Pacific Coast into the Southwest and further east. Today, Interstates 8 and 10 facilitate travel and commerce between these regions much in the way the Indigenous trails once did.

Since 2015, I’ve been heavily invested in exploring, studying, and preserving the Indigenous cultural landscape of the lower Gila River—that seemingly lonely stretch of now-dry river west (downstream) of its confluence with the Salt River near Phoenix. As I’ve highlighted in an early overview of the region, trail networks emblazoned on the region’s black desert pavements are integral threads of the area’s archaeological fabric. Earlier archaeologists such as Malcolm Rogers (noted above) and Julian Hayden (1911–1998) realized this, as well. In more recent years, archaeologists have begun collaborating with local Indigenous communities to better understand the cultural significance of such trails. Notable efforts include T. J. Ferguson and his students’ documentation of O’Odham salt pilgrimage trails through Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument and Andrew Darling’s efforts to correlate trails leading out of the Gila River Indian Community with cognitive maps embedded in Akimel O’Odham song cycles.

As part of my lower Gila research, I have also been documenting trails, both along the river corridor and through the mountainous country that forms the river’s Great Bend. It is this latter area where I want to focus. We have long been aware of a network of Indigenous trails stretching east from the vicinity of Gila Bend to the Maricopa area in the middle Gila River valley. Early explorers described this detour from the river as a shortcut when moving longitudinally across southern Arizona. It eventually took the moniker of the “40 mile desert,” as it was roughly that distance between stage stations (and water sources) at Maricopa Wells and Gila Ranch (now Gila Bend). And there is good reason to believe these early travels and trails followed Indigenous routes, because the earliest explorers employed Indigenous guides to lead them through this unknown country.

In the early 1990s, archaeologists with Archaeological Research Services, Inc. (based in Tempe) carried out a survey to identify potential impacts from the planned expansion and widening of Arizona State Route 85 between Gila Bend and Buckeye. In that effort, they encountered a number of Indigenous trails running east–west in the desert pavement along the western bajada of the Maricopa Mountains, but they did not map them to any great extent beyond the project’s footprint.

The Office of Cultural Resource Management at Arizona State University and the Cultural Resource Management Program at the Gila River Indian Community (CRMP-GRIC) collaborated on the subsequent mitigation. The CRMP-GRIC used the opportunity to expand their ongoing research into Akimel O’Odham and Pee-Posh traditional cultural properties, including trail networks. (Andrew Darling and Barnaby Lewis wrote about this research in Archaeology Southwest Magazine 21[4], and elsewhere.) Accordingly, archaeologists with the CRMP-GRIC, under the guidance of Andrew Darling, mapped a sample of the previously identified trails eastward to the foot of the Maricopa Mountains, ending their pursuit where the desert pavement petered out.

In 2017 and 2018, I worked with a team of volunteers to survey 84 miles of existing roads within the portion of the Sonoran Desert National Monument north of Interstate 8. That project was sponsored by the Conservation Lands Foundation and was designed to assist the Bureau of Land Management with managing potential vehicular impacts to archaeological sites.

Most of the roads we surveyed contoured or cut through the Maricopa Mountains. While surveying one in a major pass at the north end of the Maricopa Mountains, we began to find linear scatters of artifacts comprised almost exclusively of pottery sherds. As we flagged out the artifacts and mapped their distribution, we noticed that the linear scatters are extremely thin and straight, and they align along a uniform orientation. I began to suspect that we were picking up traces of an ancient travel corridor, but the actual trail was not visible due to the loose, unconsolidated nature of the terrain.

As we progressed westward from the pass in the mountains, we picked up another narrow linear scatter of pottery. We tracked this alignment, sherd by sherd, for approximately one kilometer (0.6 miles) until we hit desert pavement. There, at that point, we noticed a footpath impressed in the pavement and oriented at the same trajectory as the artifact scatter. This was one of the trails the CRMP-GRIC had mapped a decade prior. We continued to flag the artifacts, and we found them essentially tethered to the trail and of the same density and composition as what we’d found beyond the desert pavement. At that point, I was confident that we had identified a major trail passing through the Maricopa Mountains, even though the actual impression of the footpath was not visible due to the geomorphic context.

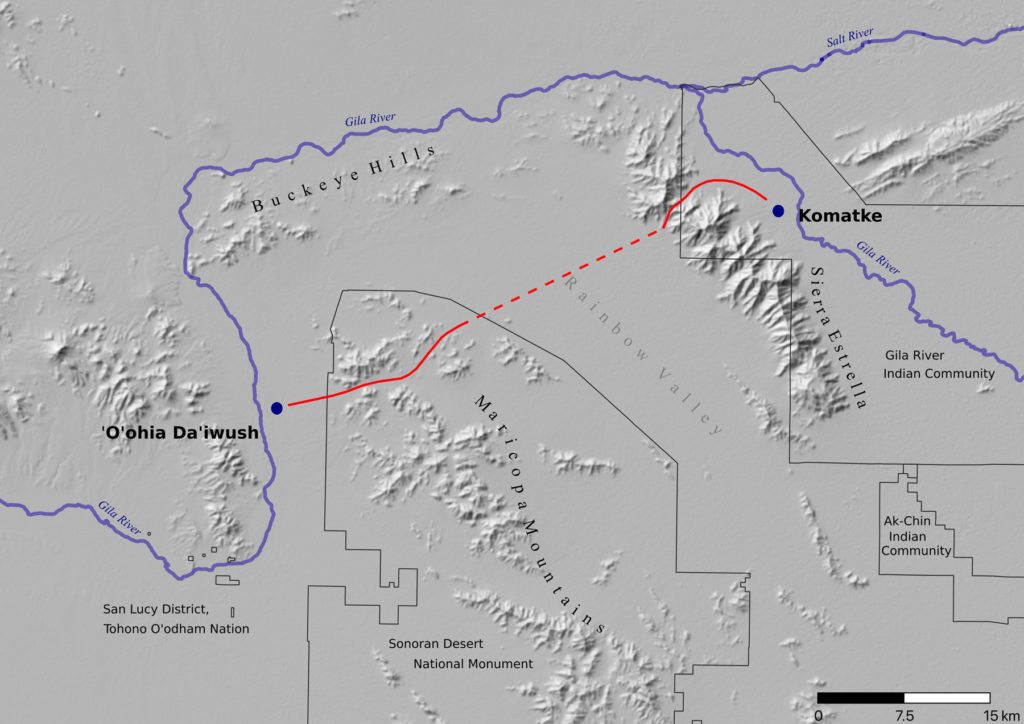

In Andrew Darling’s earlier work, he suggested that a major trail cut off the north end of the Great Bend of the Gila via passes in the Maricopa Mountains and Sierra Estrella. He based this inference in part on the accounts of Father Kino and his military escort Juan Mateo Manje, who in 1699 ventured up the Gila River from the Quechan villages around present-day Yuma on their return to the Mission Nuestra Señora de los Dolores in present-day Sonora, Mexico. They, of course, were led by O’Odham guides over Indigenous trails. Kino and Manje describe leaving the river from the village of San Felipe y Santiago de Oyadoibuise (‘O’ohia Da’iwush) on the lower Gila and cutting east through several mountainous passes before reaching the Gila once again near the village of San Bartolomé del Comac (Komatke).

Komatke is a thriving community in District 6 of the Gila River Indian Reservation, although it is now located on the opposite side of the Gila from when Kino and Manje visited. The location of ‘O’ohia Da’iwush, however, is not as certain because its residents left nearly two centuries ago. Paul Ezell suggested it was located along the river about midway between present-day Gila Bend and Arlington. That location is roughly due west of the pass in the Maricopa Mountains where I had linked the “trail-less trail” of artifacts with the footpath mapped by Archaeological Resource Services and CRMP-GRIC.

Based on these known end points, Darling suggested the trail Kino and Manje followed led them through a pass in the north end of the Maricopa Mountains, across the Rainbow Valley, and through another pass in the Sierra Estrella before reaching Komatke. He supported this position with the fact that the trails CRMP-GRIC had mapped led from the suspected vicinity of ‘O’ohia Da’iwush to the pass in the Maricopa Mountains. And from the other side of the Great Bend, CRMP-GRIC had also mapped a major trail extending westward from Komatke and through a pass in the Sierra Estrella. From these points, it was a matter of connecting the dots.

During my survey in the Sonoran Desert National Monument, I was able to extend physical evidence of this trail from its west end near ‘O’ohia Da’iwush to the heart of the Maricopa Mountains, giving credence to Darling’s suggestion. From there, however, it and the country through which it runs remained tierra incognita. I suspected that additional segments could be found and traced, but any such effort was beyond the scope of that project. Fortunately, last year the Gila River Indian Community awarded Archaeology Southwest a grant in support of our effort to continue tracing this trail through the Maricopa Mountains. After a delay due to COVID-19, we’ve finally been able to begin the fieldwork.

During the weekend of Halloween, I spent two days tracking this elusive trail with Archaeology Southwest CEO Bill Doelle and Preservation Archaeology Postdoc Chris Caseldine. Back in 2018, I had tracked the trail to a wash where I lost all trace of it. From there, though, I suspected it went either one of two ways; we just needed to find the next trace of it in order to resume the mapping. As we neared the end of our first transect, I spotted a single pottery sherd on the ground, our first artifact find of the day. From there, we began laying out pin flags as we found another, and another.

Within a matter of minutes, I knew we had found a trail segment. The flags marking the pottery pieces began to line up like a trail of bread crumbs—at least that is how Chris described it.

From there, we were off and running (more like rapidly walking). Over the remainder of the day, we mapped a nearly continuous and straight line of pottery sherds for nearly a mile and a half. Amazingly, and just as I had remembered it, the pottery was confined to a narrow corridor 10 to 15 meters wide (about 30 to 45 feet), with literally nothing outside of it. We resumed our search the following day and were able to trace the artifact trail another mile. By the end of the weekend, we had extended the trail completely through the Maricopa Mountains. And as we worked west-to-east, we noticed (unsurprisingly by that point) that our trajectory pointed directly to the pass in the Sierra Estrella where CRMP-GRIC had mapped the trail leading to Komatke. The only thing separating us was the wide Rainbow Valley.

While tracking the trail, I couldn’t help but imagine what it would have been like to walk all the way from Komatke to ‘O’ohia Da’iwush, or the other way around. It’s evident that people dropped a lot of pots along the way. Are the sherds remnants of canteens? The abundance of pottery along the sections of trail we’ve mapped speaks to the sheer volume of traffic that flowed along this conduit over the centuries it was used.

But also interesting are the types of other things we’ve found along this trail. Although 99 percent of the artifacts are pottery sherds, there is the occasional piece of flaked stone. Chris found a fragment of a metate with seemingly no purpose being in the pass of a mountain range many miles from the nearest village. I’ve found a couple shells undoubtedly from the Gulf of California. Did they fall out of someone’s basket tumpline? But what Bill found within three hours of his first day on the project takes the cake: While attempting to find the next sherd, he looked down in a totally untelling and inconspicuous place, and lying there he saw a shiny flat rock sitting on a bed of sand.

Noticing a small hole drilled into it, Bill immediately knew what it was and shouted, “I’ve found something you might want to see.” I walked over and saw a flat pendant made of schist, ground along its margins. As Bill turned it over, we noticed the underside was covered in a layer of dirt. Looking a little closer, we noticed some red paint under the dirt; Bill had found a painted schist pendant sitting for who-knows-how-long along a faint trail in the middle of seemingly nowhere.

We placed the pendant back where it had been, painted-side down, just as we had found it. The rest of the day, I kept replaying in my mind a scenario of someone walking that trail centuries ago with a necklace bouncing off their chest with every step. For some reason, the knot holding it together came loose, and the jewelry fell to the ground unnoticed. Perhaps they didn’t realize it until they got to ‘O’ohia Da’iwush, or Komatke. That necklace meant something to someone. I imagined that feeling, and that sense of loss.

Whether that’s what happened or not, that’s where my mind went. That’s how I connected with that place, piece, and time, probably because I can relate to losing a cherished object. It’s simple experiences like that that make all the difference in this line of work, and it gives me peace of mind knowing that pendant is still out there where someone left it or lost it so long ago, and where it ultimately belongs.

6 thoughts on “Following in Their Footsteps”

Comments are closed.

This is absolutely wonderful! Thank you, Aaron! And cheers to your helpers, Bill and Chris.

Thanks, Aaron! A great story and new advance in our knowledge of the Southwest!

Thanks for taking me along the journey- minus the sunstroke.

Great detective work by all! The lost red pendant along the Komatke trail would make an interesting historical novel.

Excellent article. While on survey in 1974 (TG&E El Sol-Vail) we documented several apparently prehistoric trails, some west of the Sierra Estrella, including one where I found a complete Salt Red jar laying beside the trail.

Wonderful article, I am working with Gerald Ahnert a little eyes on ground for him, Aaron on the latest Desert Track I have been studying the picture of the prehistoric trail up the bluff near Oatman Massacre site, now I cannot see this on google earth, I recently been out their and still could not find it, your picture is so vivid the trail up the slope should be as easy to spot as the one on west side of Sears Point, am I missing something or did you Lidar the pic? Maybe u could drop me a clue or two thanks for all your work and recently been looking for evidence of Burke’s Ditch for Gerald Ahnert and out to Burke’s Point, thanks again