- Home

- >

- Preservation Archaeology Blog

- >

- What’s the Point: Making an Impact

This is the first post in a new series called “What’s the Point?” Allen Denoyer and other stone tool experts will be exploring various aspects of technologies and traditions.

(December 28, 2020)—In this post, I want to talk a little bit about what happens to projectile points when they are shot. The vast majority of projectile points made in the past ended up broken—which was the expected outcome of hunting with them. Hunters could only count on one shot with a stone point, and though they might get lucky and get more, they had to plan for just one. It’s clear they would have carried a few foreshafts to allow multiple shots without having to stop and work on their equipment.

It is important to remember that projectile points are just one component in hunting systems such as the atlatl and the bow. Dart and arrow points were all hafted to foreshafts, which then socketed into the dart or arrow shafts. When they were shot and subsequently broken, hunters would retrieve the wooden element that could easily have a new replacement point hafted into it. In hunting camp settings, it’s common to find broken bases of points. Sometimes people lost foreshafts on hunts and lost points in camps, which is why we occasionally find complete points.

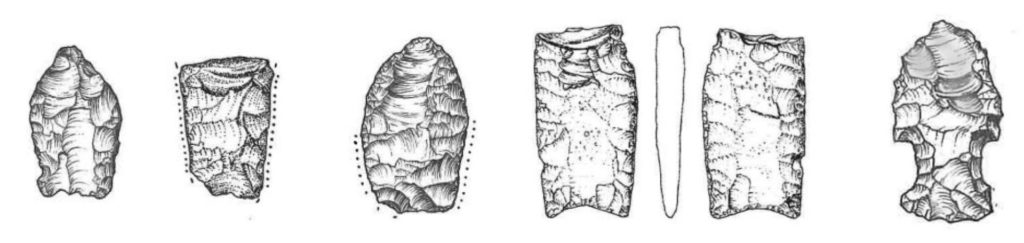

By examining the base of a projectile point, experts are usually able to discern what tradition it was made in and about how long ago it was made.

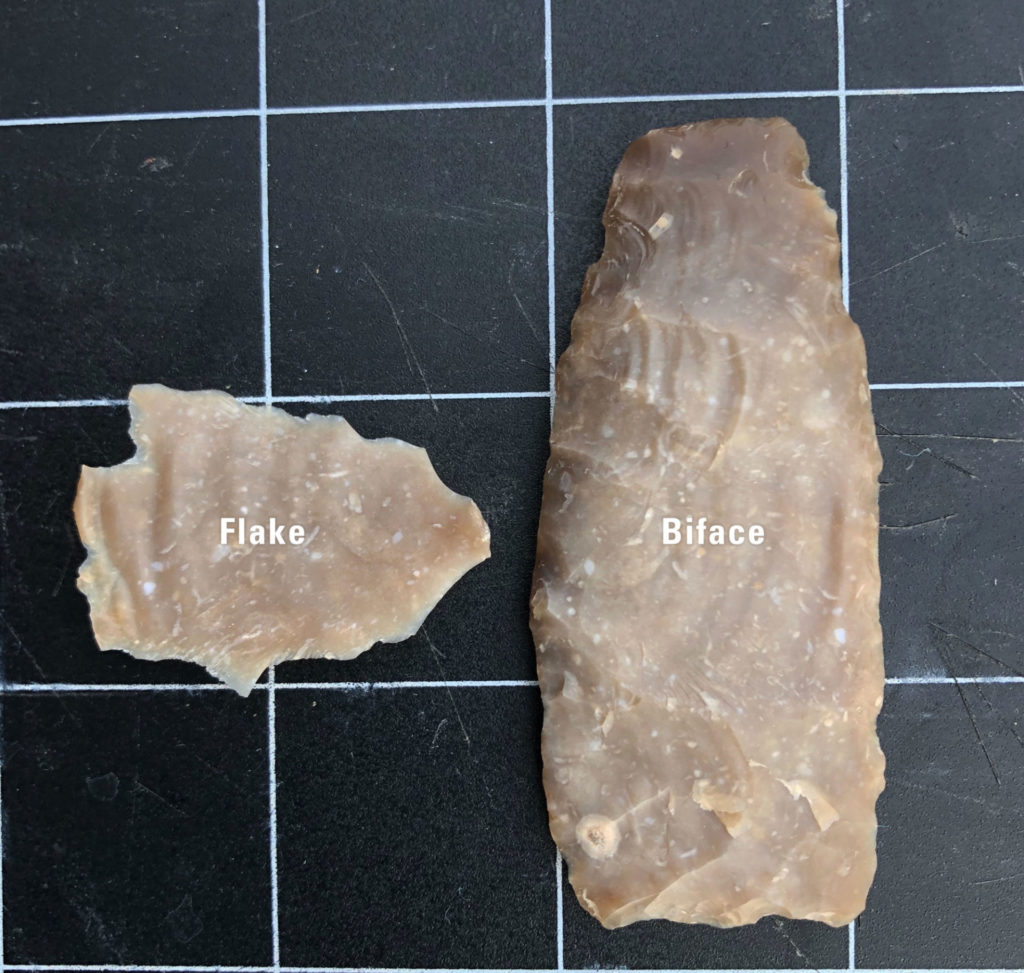

Projectile points are made by the process of striking flakes. Every flake is a wave of energy that travels through the stone to create a fracture. Controlling this fracture allows a toolmaker to shape the rock into a projectile point.

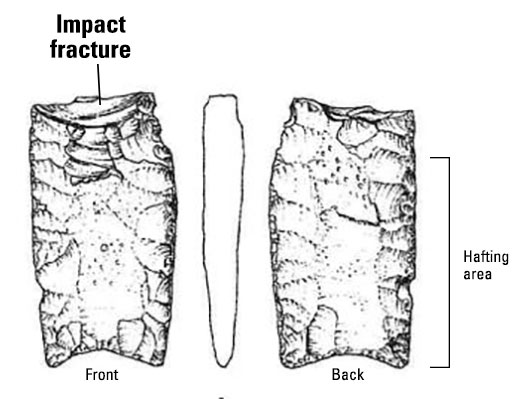

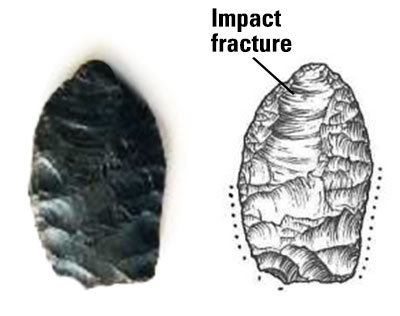

The surface of the projectile point bears the scars of these flakes, which show how the point was made. Some material types show these scars better than others. The scars can tell us a lot about the life history of the projectile point. On larger projectile points—dart points used with the atlatl—it is common to see evidence of sharpening or reworking after a break. Flake scars that originate from the point (distal) end of the projectile point are almost exclusively created through impact.

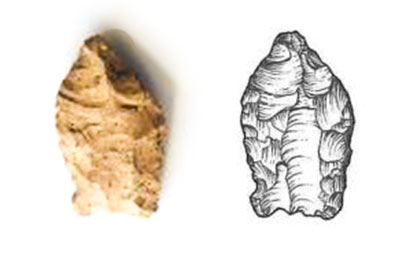

![Impact fracture. There are several different ways points can break. This San Pedro point (2,000 BP [before present]) has some flakes originating from its distal end (the tip). These were created when the point hit something hard, like bone. This impact fracture is multiple flakes, and it does not appear this point was sharpened again. This kind of breakage can occur when the point penetrates between two of an animal’s ribs.](https://www.archaeologysouthwest.org/wp-content/uploads/San-Pedro-impact.jpg)

Another way projectile points break is by receiving too much pressure from the side. This causes them to bend and snap in two. This is a common kind of fracture when making a point. Another way it could happen is if a hunter were to drop a foreshaft on hard ground.

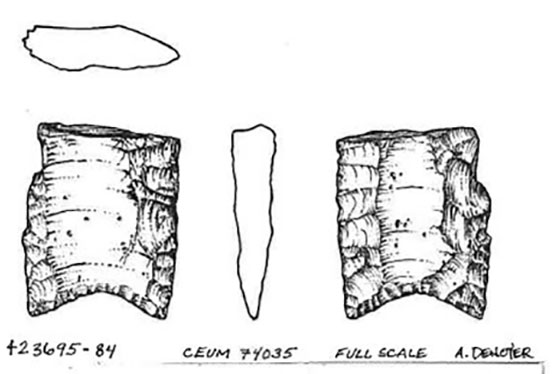

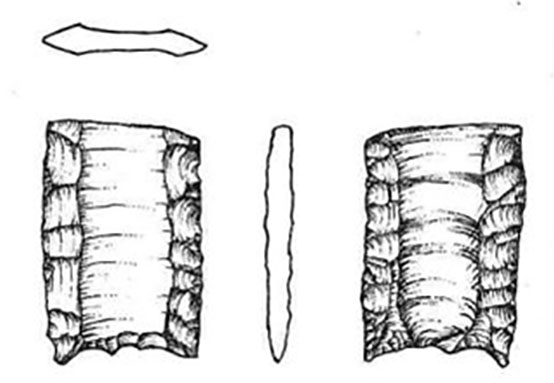

Toolmakers of the Clovis tradition (13,000 BP) and other Paleoindian point traditions ground the hafting areas so that the bindings would not be cut. Clovis and Folsom points (10,000 BP) have biface thinning flakes struck up their bases. This also allowed easier hafting.

The basal portions of projectile points usually help analysts identify their age and what tradition they were made in. These hafting areas may have remained more intact because they would have been wrapped in sinew and some kind of mastic, such as pine pitch.

4 thoughts on “What’s the Point: Making an Impact”

Comments are closed.

Explore the News

Related to This

-

Project Hands-On Archaeology

As always, Allen, fascinating. By the way, what prehistoric site was that laundromat in?

Remarkable, thanks!

Thanks much for this basic yet rarely presented information. Would love to read more from you. Ps I love Bajada also!

Thanks

I have shot flintknapped replicas into trees examining the breakage. One end of the breakage is dished out while the other halted bases breakage always has a bulb. Right at the haft and at the tied sinew. I have found many ancient broken points showing this type of breakage along waterways in streams. This to me suggests the bases had came from trees that fell in leaving only the base thousands of years later as the shaft always has degraded leaving no shaft as always when found. And the blade ends are always dished out.