- Home

- >

- Preservation Archaeology Blog

- >

- A Tonto Basin Journey

(February 1, 2021)—During my time at Archaeology Southwest, I have been afforded the opportunity to expand my research interests. I furthered a study of Hohokam irrigation that I began during my dissertation research, gained new insights into ancient trails, and became familiar with Tonto National Monument (TNM), located on the south side of Roosevelt Lake.

The impressive cliff dwellings at TNM have awed the public and archaeologists alike since the late 1800s, but the monument is more than multistory adobe structures perched on the edges of caves. Below the dwellings are fieldhouse and multi-room sites with coursed-stone masonry walls. Those structures were the focus of my work on the monument, and they soon became the first step in my Tonto Basin research journey.

It Began with Background Research

The starting point for beginning archaeological study in a new area is reading… a lot of reading. Fortunately, I was not starting from scratch.

In the early 1900s, Roosevelt Dam’s construction and operation submerged much of the floodplain along the Salt River and Tonto Creek beneath what is now Roosevelt Lake. Federal laws mandating archaeological mitigation or avoidance did not exist at the time, so we have only fragmentary information about the ancient riverine settlements before the lake enveloped them.

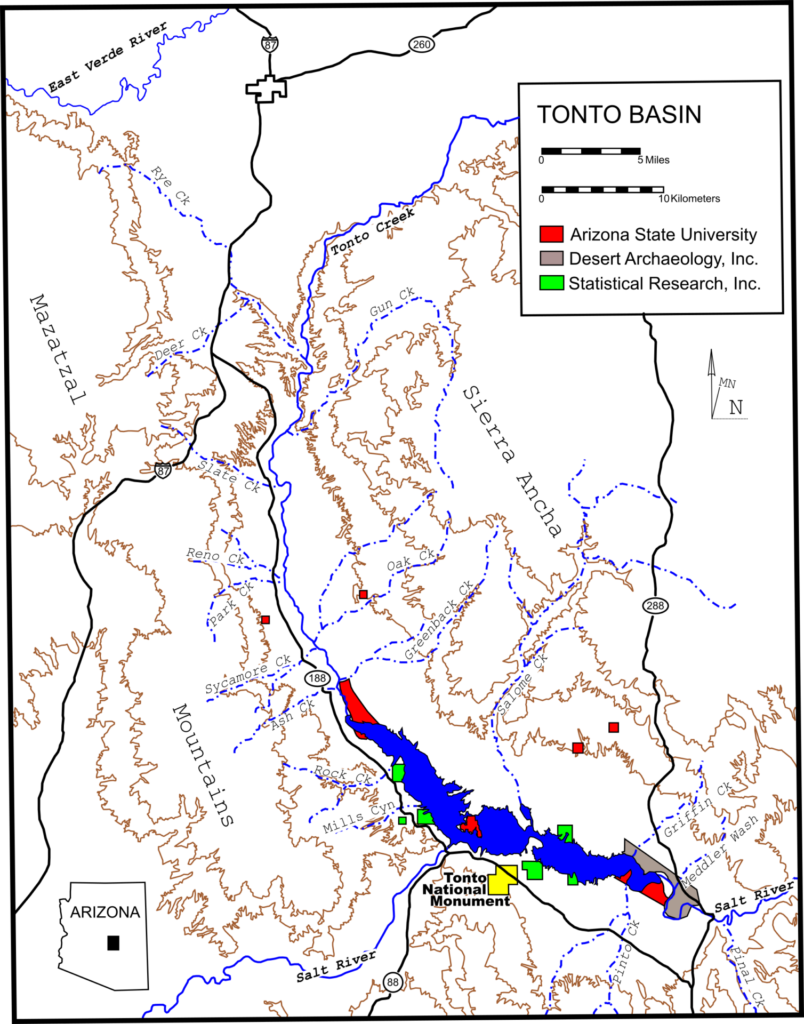

In the late 1980s, the Bureau of Reclamation (BOR) decided to increase Roosevelt Dam’s height. This time, BOR archaeologists were determined to document sites threatened with submersion during the impending high-water level. Three major projects—Roosevelt Platform Mound Study (RPMS, ASU), Roosevelt Community Development Study (RCDS, Desert Archaeology, Inc.), and Roosevelt Rural Sites Study (RRSS, Statistical Research, Inc.)—achieved this task.

The artifacts collected and documents generated during those projects are stored at the Archaeological Research Institute (ARI; now the Center for Archaeology and Society Repository) at Arizona State University. As a graduate student, I spent countless hours working there, moving those boxes, completing inventories, and rehousing artifacts into archival-grade containers (so many spiders!). More importantly, I learned the ins and outs of the RPMS project from Arleyn Simon, who was the RPMS Laboratory Director and later the ARI Curator.

That work and those conversations led me to equate the Tonto Basin with Salado, and I was not alone in this view. I have since realized my assumption was based on limited information.

It Continued by Considering the Tonto-Salado Connection

Archaeological investigations have demonstrated that people have lived in the Tonto Basin since at least the Archaic (5000–1000 BCE), and possibly as early as Clovis. The three major Roosevelt projects, however, focused on a sliver of time that corresponded with the Salado (Roosevelt and Gila phases, 1250–1450 CE). Salado polychromes (Roosevelt Red Ware) and mounds denoting platform mounds and residential compounds were scattered across the surface, so they were the most achievable focus of documentation during the allotted time frame. The foresight of BOR staff was a boon for our understanding of Salado.

Study of the Tonto Basin, and Salado in turn, may be divided into the time before the First Salado Conference and what came after. The 1976 conference brought together leading archaeologists studying the “Salado problem.” The meeting was a watershed event for two reasons.

First, different views on Salado were presented in person in one place. Although strong arguments were made for the origin (migrants or local populations?) and archaeological culture foundation (Mogollon or Hohokam?) of Salado, there was general agreement that the Tonto Basin played a role in the story.

Second, it marked the point when archaeological datasets began to drive understanding of Salado. Before the conference, archaeologists had investigated only a handful of sites in the greater Tonto Basin area, including the TNM Cliff Dwellings, Roosevelt 9:6, Porter Springs Ruin, Rye Creek Ruin, Gila Pueblo, Togetzoge, and cliff dwellings in the Sierra Anchas. In the 1970s, highway and power line projects began the slow, inexorable aggregation of archaeological excavation data. Early cultural resource management-oriented projects—for example, the Miami Wash Project and Reno-Park Creek Project—highlighted the complexity of the Tonto Basin’s ancient history. With the exception of Scott Wood, Stephen Germick, and Joe Crary, research in the Tonto Basin has largely been due to cultural resource management, as represented by the major Roosevelt projects and subsequent highway and utility projects.

The near-century of research linking the Tonto Basin to Salado makes it an inescapable aspect of research in the area. Work leading to the Second Salado Conference, presented in 1992 and summarized in Salado, edited by Jeffrey Dean, has further cemented Salado’s hold on the Tonto Basin.

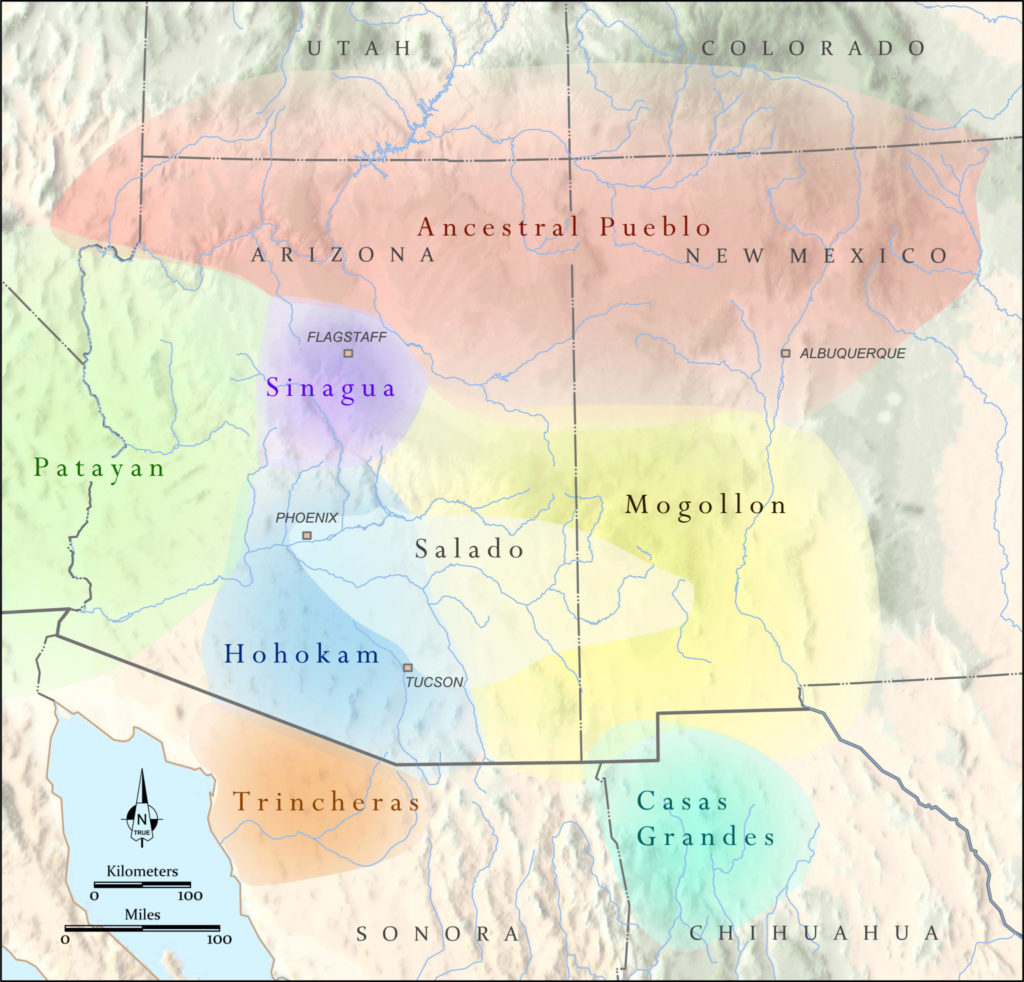

Salado spread across the Southwest during the 1300s and early 1400s, but not everyone accepted it. It appears that people in the Papaguería and lower Gila River did not accept Salado ideology. Archaeology Southwest’s Edge of Salado project, directed by Lewis Borck and Jeffery Clark, as well as subsequent work, has sought to better understand why some chose not to weave themselves into the Salado fabric. Salado was something, but not everything.

Salado in the context of other archaeological culture areas of the Greater Southwest. Map: Catherine Gilman

Then It Visited the Phoenix Basin

My archaeological background is Phoenix Basin Hohokam, with an emphasis on the lower Salt River Valley. Salado is discussed in the archaeological literature of the area, but it is a part of a longer local narrative. The end of the pre-Classic (around 1100 CE) saw people making changes: the ballcourt and marketplace systems collapsed; households transitioned from living in pithouse courtyard groups to dwelling in adobe compounds; families replaced Middle Gila Buff Ware pottery with Salado polychrome pottery; and they began burying the deceased more often than they cremated them.

In short—local farmers started doing different things. What perplexes many archaeologists is why.

Mogollon and Kayenta have a role in Salado of the Tonto, Tucson, and Safford Basins, but not the Phoenix Basin. Architecture and pottery have demonstrated that whatever brought on or spread Salado into the Phoenix Basin was not linked to migration of people from beyond the basin. Salado was something that valley residents chose, but—it seems—on their own terms.

And Now It Forges Ahead

My familiarity with Salado in the Phoenix Basin leads me to wonder what was happening in the Tonto Basin before Salado took hold. From approximately 700 CE to 1100 CE, Tonto Basin residents are considered to be colonists associated with the Hohokam tradition or locals with strong ties to the Phoenix Basin. Although Tonto Basin communities did not build ballcourts, they did live in pithouses (house-in-pit), cremated their dead, used Middle Gila Buff Ware pottery, and organized their settlements akin to the Phoenix Basin.

What happened between 1100 and the beginnings of Salado during the Roosevelt phase is poorly understood. The transitional period has eluded archaeological explanation because what people did was not as distinct as it was before and after—materially, we see this in the fact that they were not making their own decorated pottery.

Stone masonry fieldhouses and multi-room structures at TNM and elsewhere around the Tonto Basin should be critical for gaining a better understanding of what was going on in the basin before Salado. Until we pin this down, the question of how Salado came together in the basin remains open. Salado did not suddenly appear one day, but developed over time. My work should help unravel this. To be continued…

6 thoughts on “A Tonto Basin Journey”

Comments are closed.

Dear Chris,

Like you I have been curious about the apparent shifts in lifestyles adopted by the people of central southern Arizona around the 1200s. An article some years ago spoke of the likely exponential use of wood resources in the climax pattern Sonoran desert and how wholesale destruction of the limited supply seems to parallel the appearance of puddled adobe, internment of the dead instead of cremation, and imported pottery; all of which are tied to wood availability. Is this theory still given any credence among archaeologists today?

From Chris: Yes, resource depletion continues to have credence among archaeologists. A recent study by David Abbott, Doug Craig, and others (American Antiquity Vol. 84, Pt. 2, pages 317-335) found that population stress and wood usage may have contributed to the shift from pithouses to adobe compounds at Pueblo Grande, but regional and macro-regional social processes likely had a bigger impact. The shift to adobe/masonry structures ca. 1100 CE occurred across different environments within the Hohokam region, so I suspect that wood depletion would be one of many factors. A replication of the Pueblo Grande study in the Tonto Basin is needed to understand the architectural transition there.

I have a theory about the Tonto Basin … worked there at O’Rourke’s Camp and prehistoric sites with ASU and Soil Systems in the early 1980s. Would love to share my preliminary data – very rough, but I have been out of the area for years. I am planning on being back in the near future and can share.

Chris, are there any t-doors at Tonto sites?

From Chris: There are T-shaped doorways mentioned at a cliff dwelling in the Sierra Anchas and to the east, and at a compound on the southside of the Salt River near Pinto Creek. There are a few doorways remodeled into “half T-shaped”, like an upside down L, at the TNM cliff dwellings.

Hi Chris,

Im hoping you could present a power point lecrure to the Taos Archaeological Society in Oct or Nov? Please write me Phil Alldritt at taoscuba@hotmailcom if this is possible.

Thank you