- Home

- >

- Preservation Archaeology Blog

- >

- What’s the Point: All about Clovis Points

This is the second post in a new series called “What’s the Point?” Allen Denoyer and other stone tool experts will be exploring various aspects of technologies and traditions.

(February 9, 2021)—In this post, I’ll explain how people made Clovis points and what is important to look at in order to recognize them. You’ll see that it’s possible to read a Clovis point like a map.

Background

Over most of North America, 12,000 to 13,000 years ago, ancestral Indigenous people were making distinctive fluted projectile points known as “Clovis points.” Clovis points are easily recognized because of their large size, their exquisite craftsmanship, and the beautiful stones toolmakers chose for them. Although there are regional differences in style, the technology for making the points is the same.

Hunters used these dart points to bring down mammoths and other now-extinct large game animals. Through their mobile lifestyle, people subsisted on these and other animals, as well as plant foods.

Clovis archaeological sites are rare. Points are found at single-episode kill sites, multiple-episode kill sites, campsites, in caches, and as isolated artifact finds. Campsites and caches are extremely rare finds.

Our best information on how Clovis points were made comes from caches. One cache seems to have been with a burial, but the purpose or meaning of other caches is not clear. Caches often contain earlier-stage bifaces, unused finished points, and even some reworked points. Points in a cache typically show a wide range of stone types, often from long distances apart, which suggests these people were traveling great distances to obtain high-quality stone.

Clovis points range in size. At the time of manufacture, the average Clovis point was probably about 4 to 5 inches long. The vast majority of these points were broken when they were used, however, and re-sharpened if possible. Experts think hunters may have used the largest examples as knives or on thrusting spears to finish off an injured mammoth.

Flake Maps Reveal How People Made Clovis Points

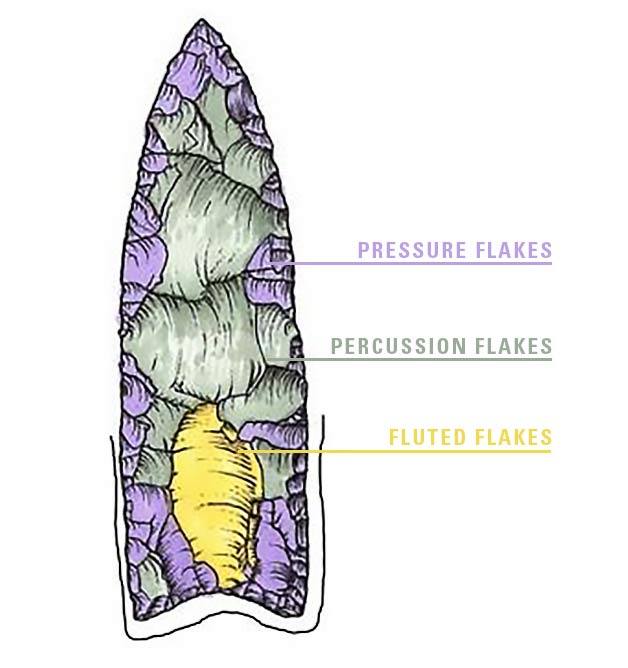

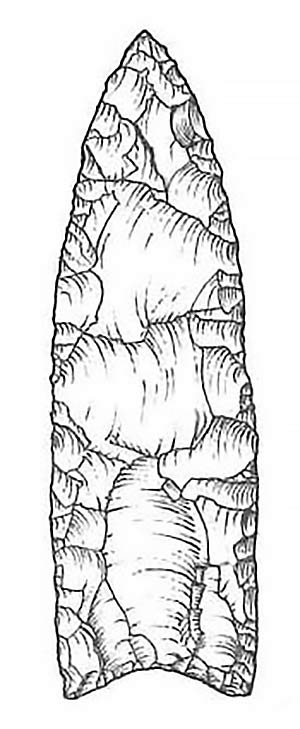

This is an illustration of a replica point that shows a lot of the flaking details you can expect to see on Clovis points. Note the colors, which will guide the following discussion.

Flute Flakes

The yellow flake scar is a basal thinning flake called a flute. Both faces of a Clovis point were often fluted in the final stages of manufacture. In technological terms, this is a percussion biface thinning flake struck from the base. These flute flakes usually extend about one-third of the length of the point. The point bases were thinned for hafting.

The basal margins are heavily ground to about the length of the flutes. The black line outside the point indicates the ground area. Grinding covers the area of the point that would have been wrapped in its haft. No preserved examples of hafted Clovis points have been found.

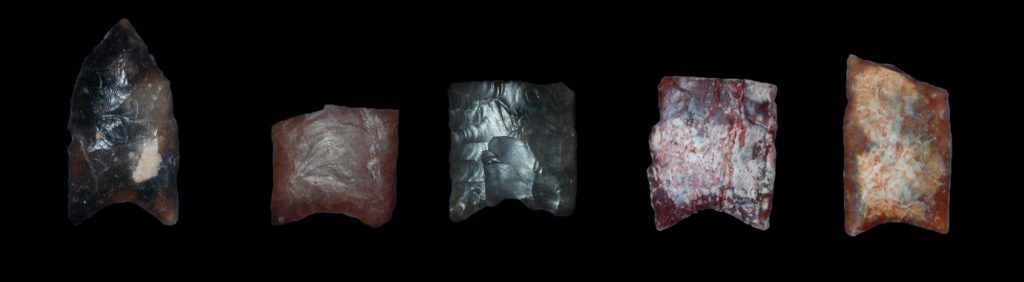

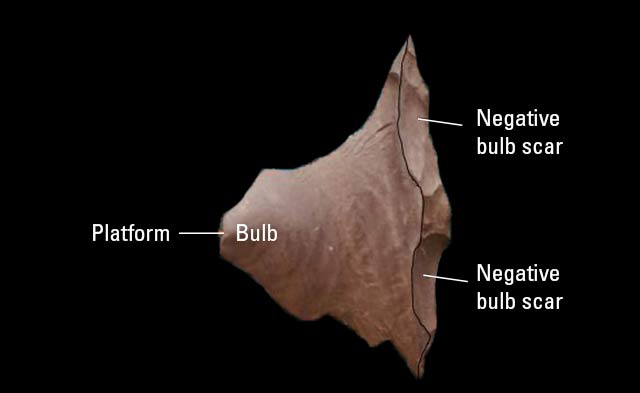

Here are some examples of fluting and flute flakes. Flute flakes are very distinctive.

Percussion Flakes

The light green flakes are called percussion flakes. These were struck during the earlier stages of manufacture, using an ivory or antler tool (which flintknappers call a billet). Those strikes left broad flake scars across the biface. The wide spacing between flakes allowed faces to be thinned with only three or four flakes, sometimes.

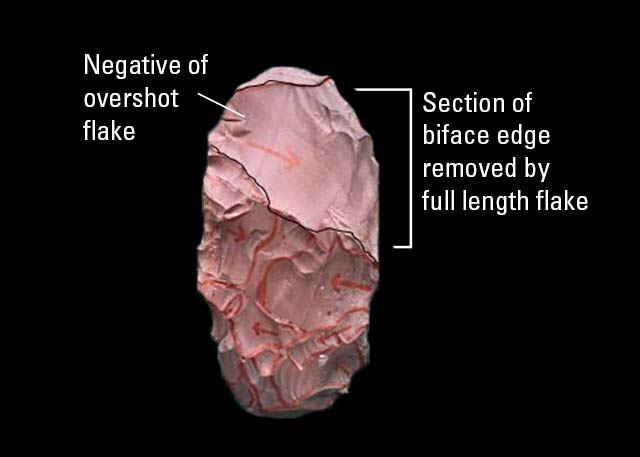

People used early-stage bifaces as cores for striking the large flakes that would become points and tools. Overshot flakes travel all the way across bifaces and remove some of the margin on the opposite side of the biface. This is a common thinning strategy in Clovis.

|

|

|

Pressure Flakes

The purple flakes are pressure flakes from the final finishing work on the point. Some points show very little pressure flaking, and others show much more extensive pressure flaking.

It appears that Clovis points often started out mostly percussion flaked. Through use and reshaping, they came to have have more extensive pressure flaking across their surfaces. Clovis knappers took care to preserve the flute scars, and did not pressure flake across them if they could help it.

The final step was the heavy grinding to margins of the base. This was done to all finished points, and is a good indicator that the maker considered the point to be finished.

12 thoughts on “What’s the Point: All about Clovis Points”

Comments are closed.

Doggone it, Allen Denoyer, we’d better get back to having your flintknapping classes soon or I’m gonna go crazy. Someday–SOMEDAY–I’m gonna get good enough to at least do a passable Clovis point–one that doesn’t start out at four inches and end up one-half-inch.

Very helpful diagrams! Thanks for sharing your knowledge.

GOOD STUFF!!

I have found a perfect Clovis point. The one u only have resin cast of, but a real one

Are the flutes symmetrical on both sides? Having about the same shape and length? Are true points exhibit wear or polishing by erosion or wear?

Do you have any pictures of the tools used to make the Clovis point. I would like to compare them to the store tools that I have found

For question 4

The flutes on Clovis points tend to match up pretty well, but there is tons of variation. You can have one face with a really nice flute, while the other side barely has one at all. Some have multiple basal thinning flakes on them. Clovis points can be reworked and most of the flute scars get obliterated.

If the point was on the ground surface for a long period of time, many of the stones they are made out of will weather and develop a patina on them.

Some stone weathers very fast and dramatically.

Clovis knappers ground the basal edges of there points heavily, this is not weathering.

I hope this helps.

Is it possible to find a clovis point that has no basal grinding. I may have one.

Can you tell me if a Clovis point can be double ended, or no flute? I would like to send you a picture of an arrowhead found in northwest Arizona

Hmm…I just stumbled on your article, and looking at the pictures and descriptions, I believe I have what I’d always thought to be a large spearhead, but now think that it may in fact, be a very large Clovis point. It’s about 9″ x 3″ and entirely whole. It was given to me by my late mother several years ago, who had found it on her property at the southernmost tip of Baja California Sur, in Mexico. Could you offer a suggestion as to how I might be able to have it authenticated?

I once ran into you on the Tiger chert quarries. I recently found a great methed to make Clovis: Get 2 slats of oak 10 to 12cm long, shapped as if cut from a yardstick. Pitch glue 2 wood buttons onto one end of each board. Wrap the tip of preform in leather then sandwich it between the boards and wrap tight with string. The buttons at the base end, Then flute. It stops endshock completely. Good luck.

I have a Clovis point that I found close to 60 years ago on a glacial sand dune in northwest Ohio. I have full data for it but don’t know if there is a clearing house / organization doing this work collecting data?