- Home

- >

- Preservation Archaeology Blog

- >

- George McJunkin: Standing at the Intersection of B...

(March 4, 2021)—Betteridge’s Law of Headlines, credited to British tech journalist Ian Betteridge, goes approximately like this: “Any headline that ends in a question mark can [often] be answered by the word ‘no.’” Examples abound.

Similarly, with regard to archaeology and media reporting, almost any headline containing the phrase “could rewrite history” can be amended with “but probably not.” Again, examples abound.

Still, however rare they may be, exceptions have occurred. Just such a case is that of George McJunkin, ostensible “discoverer” of the Folsom material culture and an impressive figure in his own right. To understand the full importance of the man himself, his discovery, and what all that means to American history, it’s important to understand certain contexts.

The Black Cowboys

It’s difficult to fathom the gravity of this through the lens of time, but the United States of America was barely into its 80s when half of it decided to secede because it didn’t want to give up owning human beings as property—prompting the other half to declare war.

At the close of the war, newly emancipated Africans faced a new set of problems, not least of which was employment. Robust proposals for post-war Reconstruction that included progressive and aggressive assistance for the formerly enslaved died—literally—with the assassination of President Lincoln. President Andrew Johnson took a much more libertarian approach to the topic. To give just one example: During the war, the Union Army had distributed all confiscated lands to the formerly enslaved people who’d worked them. Johnson gave them right back to the former landowners and slaveholders.

In most other respects, President Johnson left the process of Reconstruction entirely in the states’ hands, which allowed them to do things like pass the draconian “black codes” that severely restricted African-American freedom in the workplace and elsewhere. Johnson would eventually earn himself an impeachment for his avowed obstructionism vis-à-vis civil rights; the Civil Rights Act of 1866 became the first act passed over a presidential veto; the Fifteenth Amendment gave Black people the vote four years later; and things started looking up at last—for exactly seven years. Then an intensely debated presidential election resulted in a “compromise” that included the end of Reconstruction and passage of the even-more-draconian Jim Crow laws.

Conditions were better in the northern states before and after the war, but not much better. Although there were indeed jobs for newly freed African-Americans in the north, they were very limited and often underpaid.

Meanwhile, Anglo-Americans had been surging west into lands formerly inhabited entirely by Indigenous, Spanish, and Mexican people. And they weren’t about to do all the hard labor themselves. By 1860, more than 30 percent of individuals working cotton farms and cattle ranches in Texas were enslaved. This inspired many Texans to fight on behalf of the Confederacy, only to discover upon return that much of their stock had drifted into the hinterlands in their absence (this was before the invention of barbed wire), and that the most-skilled cattle wranglers for hire were the very people they’d previously forced into doing the job for free.

Demand for this kind of labor surged when ranchers began supplying cattle to northern states, where beef prices were nearly ten times higher. There were no railroads to transport herds at the time, so they had to be driven by cowboys who lived in harsh and dangerous conditions on the open range for weeks or months at a time. For freed Black laborers looking for steady jobs where they shared camaraderie with (mostly) other Black crew members, the work appealed.

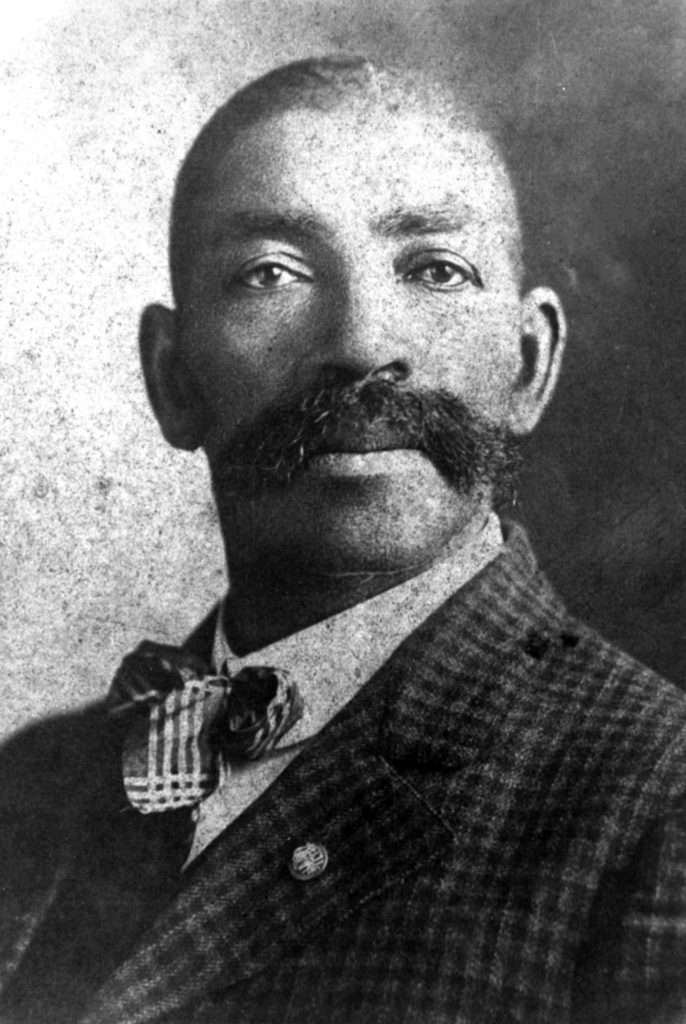

Altogether, historians estimate that at least one in four historical cowboys were Black. Famous—or what should be famous—examples include Bass Reeves, Bose Ikard, Nat Love, Bob Lemmons, and Bill “Bulldog” Pickett.

George McJunkin

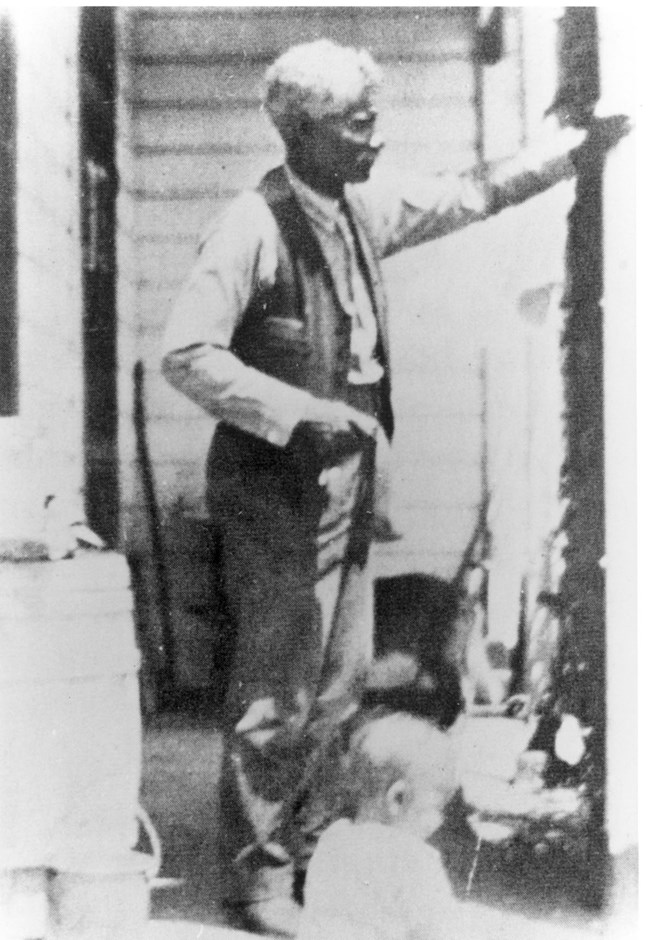

Not often included in that list is George McJunkin. He was born into slavery in Texas in 1851, on a ranch where his father—who’d purchased his own freedom years before—worked as a blacksmith. He learned riding and wrangling from Mexican vaqueros who stayed behind when the men went away to fight in the Civil War, and he heard stories about the aforementioned Black Cowboys from the moment the war ended.

Young George would often sneak away after his chores were done to hear stories from cowboys working the ranch or passing through, and he was fascinated by the equality that seemed to flourish among Anglo, Mexican, and Black cowboys. He also had a sharp and curious mind, and was particularly fascinated by natural history. By 1867, now an accomplished horse-breaker for the ranch, McJunkin left a note saying “tell [my parents] I’m going to be a cowboy and look for a school” and struck out on his own.

McJunkin gained the respect of several major ranch owners and managers, becoming the wagon boss for the Hereford Park Ranch, manager of the XYZ Ranch, and finally foreman of the Crowfoot Ranch in northern New Mexico. He spoke fluent Spanish, occasionally traded horse-breaking lessons for reading lessons, and was even said to play a mean fiddle.

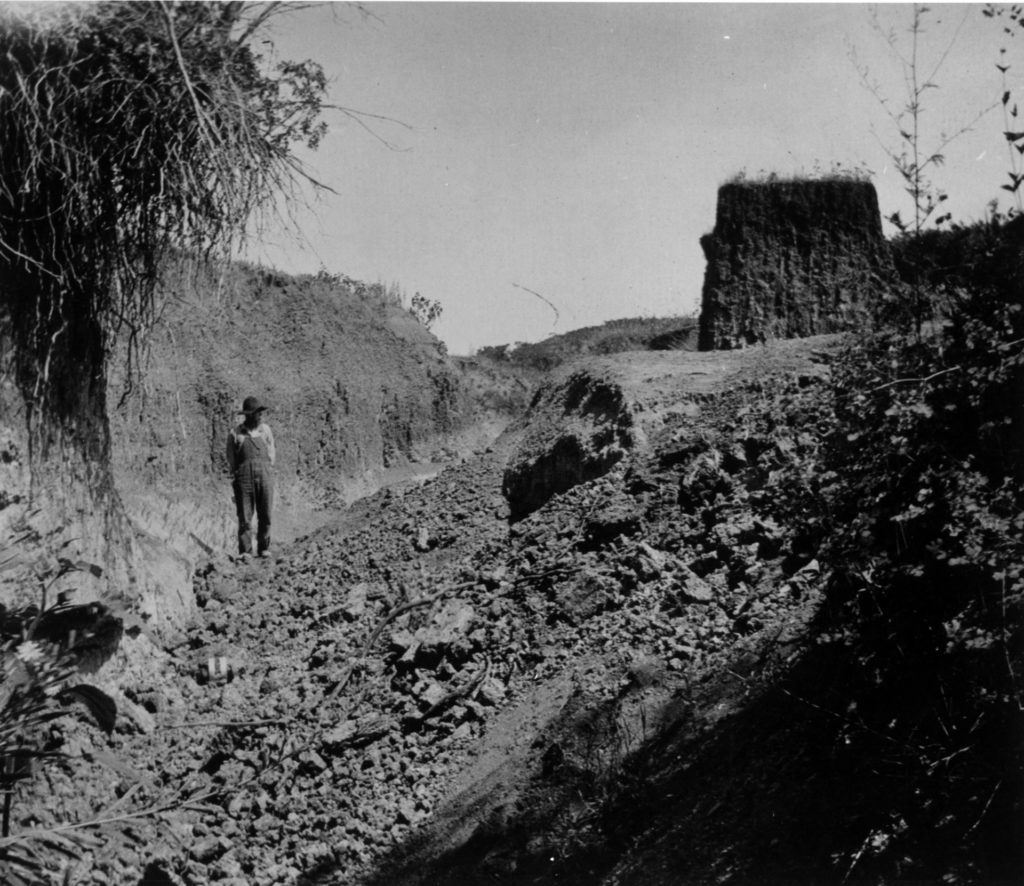

In August 1908, a massive flood destroyed a great deal of Folsom, New Mexico, the town nearest to where McJunkin worked and lived. While checking his fences after assisting the rest of the town with body recovery, McJunkin and his friend Bill Gordon made a curious discovery: Roughly 15 feet down a steep embankment cut back by the flooding, they found large bones that definitely weren’t cattle, and looked too big even to be modern bison.

McJunkin knew the site warranted further evaluation, and immediately set about trying to make that happen. Unfortunately, he died in 1922, before the scale and importance of the find was understood.

American Archaeology and Deep History

Meanwhile, American archaeology—still a young discipline at the time—was battling its own understanding of the past, and McJunkin’s discovery would further call into question all that researchers thought they knew about the North American past. By establishing the deep Indigenous antiquity of North America, McJunkin’s discovery helped break down racist and prejudicial thinking in American archaeology.

Because Indigenous peoples of the New World didn’t have steel tools, let alone wheeled carriages or guns, European colonialists assumed they must have only recently arrived. This 18th-century viewpoint—later formalized in the US as the cultural-evolution model of Lewis Henry Morgan—posited that human cultures go through inherent stages of progress. As early as the 1600s, European moral philosophers postulated a tripartite division of human social evolution: hunting or savagery, herding or barbarism, and civilization. It was an inviolable ladder that led in only one direction, with those very philosophers and their culture sitting squarely on top.

Because of this, leading authorities of the day refused to accept a human presence in North America any older than about 3,000 years ago. A convenient view, all things considered—it’s easier to take land away from people who haven’t been around very long and are somehow savage and inferior by Euro-American standards. By such means are groups delegitimized, or dehumanized, or both. (This way of thinking was, of course, also behind the mindset that it’s completely acceptable to import masses of unwilling Africans to tend one’s fields, cook one’s food, and nurse one’s children.)

Take the case of the Moundbuilders. In 1787, just over 100 years before McJunkin would be hired by a New Mexico ranch foreman, Thomas Jefferson published Notes on the State of Virginia and included his own archaeological analysis of the region. Jefferson sought to make sense of the archaeological mounds on his property. The third president of a new nation, slaveholder, and amateur archaeologist excavated a mound on Monticello’s grounds, and, based on his findings—and very much against popular opinion—concluded that the sites were created by Native Americans. Scholarly attention did not return to the Moundbuilders until 1840, just a decade and some before McJunkin was born into slavery.

Ephraim Squier and Edwin Davis undertook their own study of the Moundbuilders and published Monuments of the Mississippi Valley in 1848. They analyzed reports and investigated more than 200 sites. Their conclusions? The savage Indians could not have built the Mounds. The Moundbuilders simply had to be a more civilized—but not too civilized—predecessor, probably from Mexico or Central America. They couldn’t be related to the current Indigenous groups in the region.

In 1873, the Chicago Academy of Sciences opined that it was “preposterous” that “Indians” had anything to do with creating the mounds.

In 1879 John Wesley Powell, of Civil War and Grand Canyon fame, became head of the Bureau of Ethnology, and he hired Cyrus Thomas to further investigate the Moundbuilders. Fifteen years later, after an analysis of 2,000 sites across 21 states, Thomas concluded the mounds had, in fact, been built by Native American ancestors. He’d begun his analysis with strong feelings to the contrary, but the evidence became overwhelming. Finally, in 1894, while a Black Cowboy was breaking horses in the west, Native Americans were credited with the ingenuity of a wide-reaching, thriving culture.

It was a start. But lingering over all that was the Morganian notion that human cultures evolved in a straight line and on a narrow path—and in that perspective, Native American Tribes did not appear to have “gone very far” prior to European arrival. So, they must not have been here for very long.

The Folsom Site

Science has its own history, and every subfield has stumbled through its own process of learning new things. For its part, the Folsom site is often the prime example used to show the importance of archaeological context. The precise location or provenience of an artifact within a site is often more informative than the artifact alone. This quite basic tenet of archaeological investigation was a brand-new concept when Jesse Figgins of the Denver Museum came to examine the Folsom site in 1926, drawn at last by the interest McJunkin had generated.

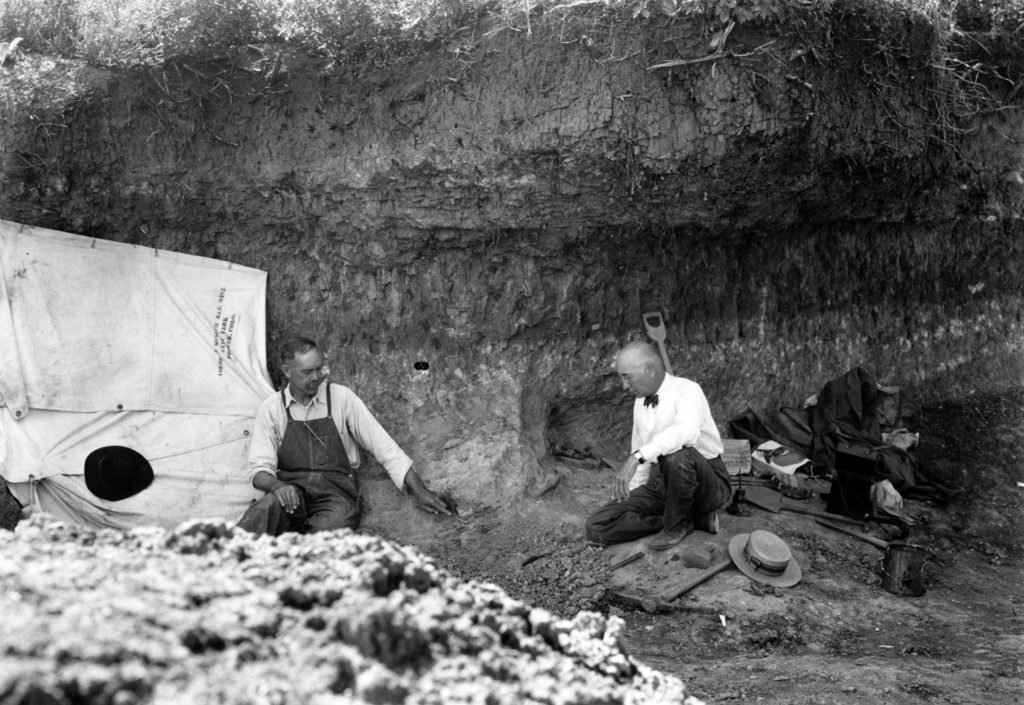

paleontologist Barnum Brown on September 4, 1927. © Denver Museum of Nature & Science

Figgins was looking to collect samples of the extinct Bison antiquus for the museum, and wasn’t particularly interested in a potential archaeological site—again, it never occurred to most “experts” at the time that people were in North America that long ago. Still, when people started talking about projectile points in and near the site, Figgins called the excavators to instruct them to leave the points and bones in place so they could be studied together. Thus, when a fluted point was discovered tucked into the ribs of the Bison antiquus, local archaeologists—including A. V. Kidder of later Pecos and Bears Ears fame—came to investigate. Given the point’s location between the ribs of a long-extinct species of bison, the conclusion was unavoidable: People had been in North America for at least 10,000 years. History books would indeed have to be rewritten.

The subsequent discovery of Clovis just a few years later would set the clock for initial population of the Americas back by another several thousand years, and at this point the amount of sites with confirmed pre-Clovis dates continues to set it back even further. But Folsom was the first. The chance discovery of a Black cowboy with a sharp mind who knew better than to pilfer or ignore something of obvious historical importance signaled the demise of a long-held conceit about Indigenous cultures and the concept of cultural evolution.

Our biases as researchers frame the way we interpret the past, and although we are improving past the long-held mistakes of our predecessors, we still fall victim to our biases. Until fairly recently, George McJunkin was rarely identified as the discoverer of the Folsom site in text books or publications. And people are still too quick to credit long-lost white people or even space aliens with the genius of Indigenous ancestors around the world. Challenging these misconceptions, and giving proper credit to the challengers, helps validate what Indigenous peoples have been saying all along: We have been here since time immemorial.

2 thoughts on “George McJunkin: Standing at the Intersection of Black History and American Archaeology”

Comments are closed.

Explore the News

-

Join Today

Keep up with the latest discoveries in southwestern archaeology. Join today, and receive Archaeology Southwest Magazine, among other member benefits.

Great article, interesting read…I believe the passage of time causes loss of correct information for whatever reason, but when this information can be corrected I deeply believe that it should. This is just such a case thank you.

I remember looking up George McJunkin years ago on the internet. Being a avid fossil & history buff , I was interested in more information. I could barely find any articles or pictures of George McJunkin back then. Glad to know that this history will live on and not be forgotten.