- Home

- >

- Preservation Archaeology Blog

- >

- Think Before You Bolt That Rock

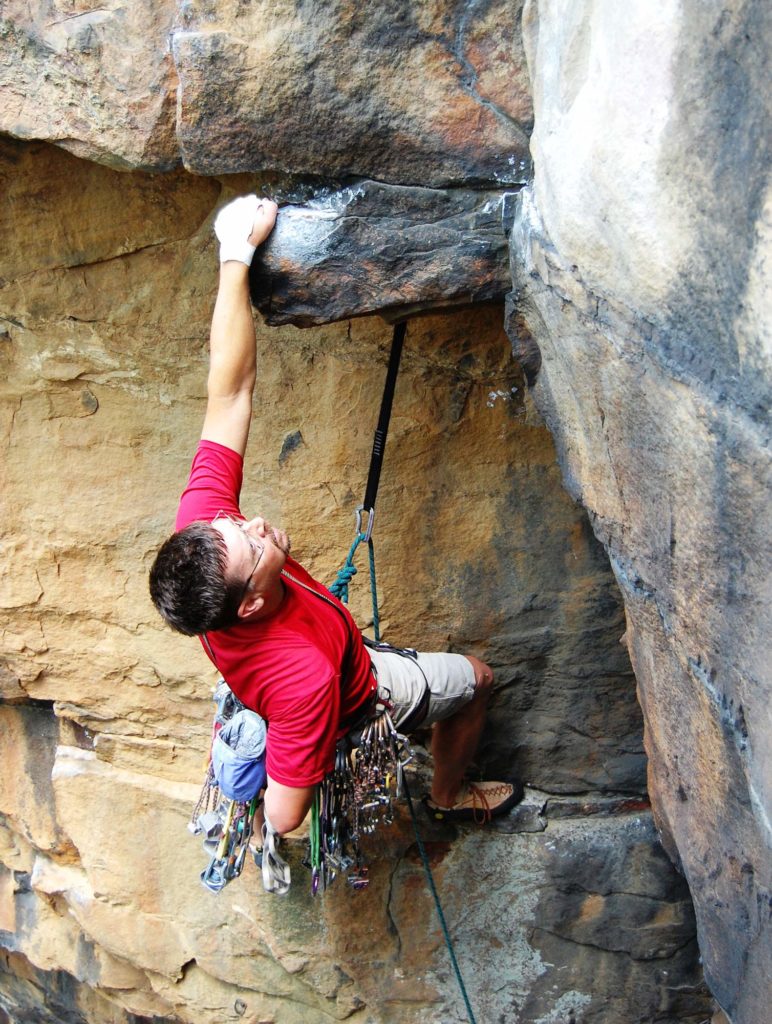

(April 15, 2021)—Two people climb the same stretch of a sandstone cliff face in eastern Utah. Centuries stand between them. Both climbers pause at the same spot, each evaluating the cliff face with their own culturally specific priorities. Instead of taking a moment to evaluate his relationship to the land and its people, today’s rock climber thinks of himself and his afternoon of pleasure. He pulls out his rock drill, points it at the cliff face, and drives the bit into the rock. Mere inches to the right lies a remnant left behind by the Indigenous climber: an anthropomorphic figure with a spear, facing the bolt as if standing sentinel, anticipating this act of violence.

This act was a violation of the Archaeological Resources Protection Act of 1979, and the damage caused can never be fully restored. Even touching a rock art panel can cause irreparable harm.

As a field archaeologist who worked in cultural resource management for more than a decade, I’ve seen some of the worst site damage and vandalism, on repeat, in every state. One project in particular comes to mind when I think of rock climbing damage: a survey surrounding a popular climbing area in southern New Mexico. Pictographs stood beside crevices caked with white climbing chalk and finger grease. Intense foot traffic from campers, hikers, partiers, and climbers denuded rockshelter floors. People left behind gross trash like nail clippers and dental picks. We watched a place we fell in love with disintegrate over the course of a summer.

Rock climbers, your access to public lands is at stake. As an archaeologist with experience in responding to archaeological resource crimes, I suspect that all route-building activities, especially installing bolts, removing vegetation, cleaning rock faces, or removing loose rock, come with a high risk of violating cultural resource laws. Before you bolt and before you climb, ask yourself: Do I understand the context of this place within the local and Tribal communities? Do I have the knowledge required to determine whether this route traverses an archaeological site? If not, stick to the well-known climbing spots, seek out relevant training, and do the work to get to know your community. Access Fund works to promote responsible climbing and maintain access for climbers on public lands through comprehensive “gym to crag” training in stewardship and conservation. (Read Access Fund’s statement on the bolting of a Moab-area petroglyph panel on public land here.)

New outdoor recreationists have seemingly materialized out of thin air over the last few years, and damage to fragile archaeological landscapes seems to be at an all-time high. How can we archaeologists provide better outreach and education tailored to the needs of our many audiences? We need to work to promote Leave No Trace and Visit With Respect ethics in this new generation of public lands enthusiasts. Stop Archaeological Vandalism, an outreach effort spearheaded by the Utah Public Archaeology Network, provides ways for concerned citizens to get involved in site stewardship and report damaged archaeological sites within the state of Utah.

It’s our responsibility as community members and good land stewards to report damage and vandalism to law enforcement, just as this rock climber did. Too often we may assume that someone else already knows about damage, or embrace the cynical assumption that no one cares. Every law enforcement officer and archaeologist is indeed responsible for thousands of square miles of public or Tribal land, and federal land management offices are indeed hampered by a lack of funding and staff, leaving them without the resources to adequately protect archaeological sites. But the squeaky wheel gets the grease, and you lose nothing by filling out an online form or making a phone call.

Remember that freshly damaged sites are crime scenes. Do not launch your own personal investigation or restoration. You will likely disturb forensic evidence. So don’t pull out climbing bolts—report! Let’s inundate law enforcement with reports so they understand how concerned we are about archaeological resource crimes.

No matter where we travel in the United States, we are on the traditional lands of living, contemporary Indigenous groups who still defend their ancestral homeland. Programs like the Ancestral Lands Conservation Corps train new generations of Indigenous young adults in historic preservation, conservation, and land management issues. At a bare minimum, these lands deserve respect; in an ideal world, they deserve remediation from historic and ongoing abuse. This irresponsible rock climber saw a cliff face as a personal challenge, perhaps, and as an inanimate object indifferent to his destructive modifications. But every cliff face, boulder, or ridgeline can be appreciated—without leaving a trace—as a wonder of geology, a shared public resource, a shrine, a story, a home, a place of origin, a being, or a relative.

At SaveHistory.org, we center Tribal perspectives about archaeological resource crime and emphasize respect for the living connections between ancestral sites and descendant communities. We actively seek tips about archaeological resource crimes, no matter the land jurisdiction, and stories from Tribal stewards about why ancestral sites deserve respect and protection.

One thought on “Think Before You Bolt That Rock”

Comments are closed.

Nicely said Shannon! Thanks for highlighting the responsibility we all share for carrying heritage forward for future generations.