- Home

- >

- Preservation Archaeology Blog

- >

- Fifteen Pipes

Val Freireich, Volunteer

(June 30, 2021)—Fifteen stone pipes in a plastic bag. Other than potsherds, fifteen of a single type of artifact in one place has been a rarity during my volunteer work on Archaeology Southwest’s Robinson Collection Project.

Fifteen steatite stone pipes. The quantity—and then their quality—struck us as we opened the bag. Patrick Hager (my partner for the day), Jaye Smith (our team lead, and I were amazed. Our initial examination revealed fourteen greenish steatite stone pipes (most complete, a few broken, and some apparently works in progress) and one broken pipe made from an indeterminate type of volcanic rock.

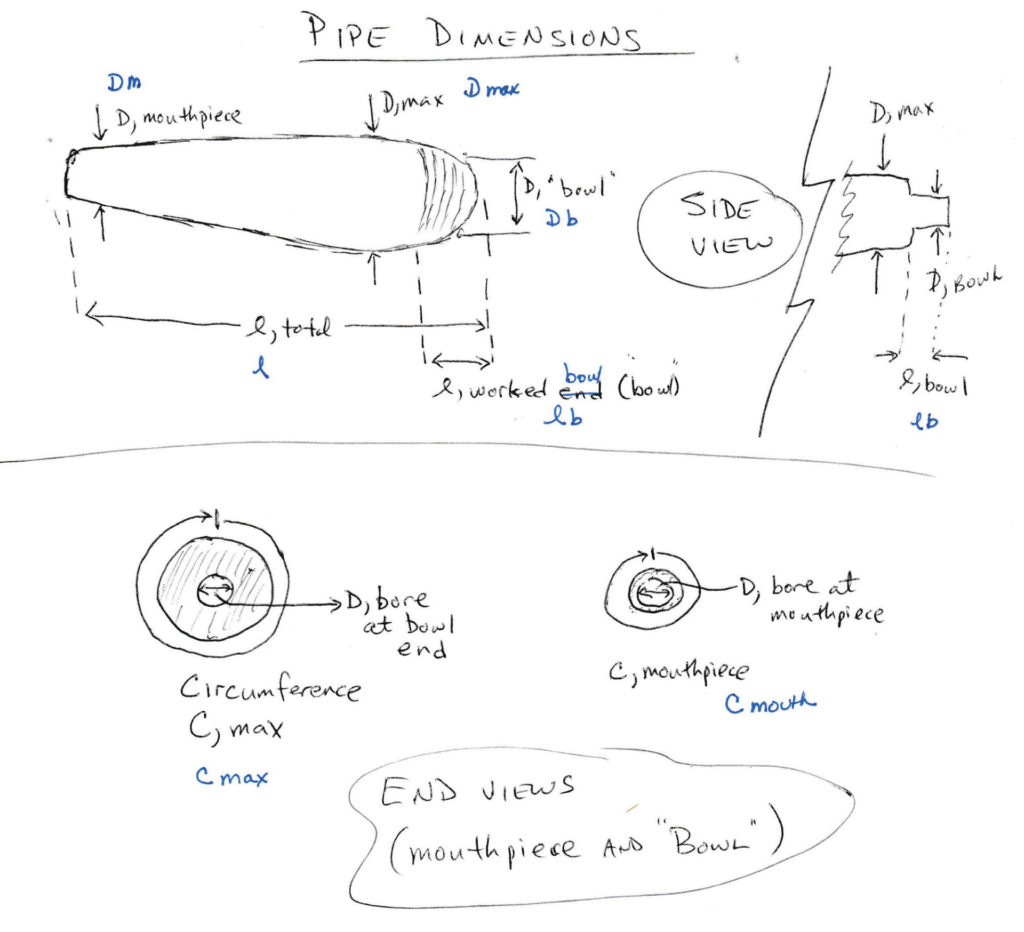

We are lucky—it’s our job to describe each artifact in this portion of the Robinson Collection Project as fully as possible, including metric measurements, so that the information will be accessible and useful to future archaeologists. We spent several hours inspecting and measuring each individual pipe.

Examining the pipes so closely allowed us to see distinct, narrow lines cut into the stone by the pipe-maker, presumably signs of preparation for completing the shape of the unfinished pipes. The quantity of such similar artifacts provided us with experience. With each new pipe, we saw more of the workings and the pipe-maker’s plan and methods. Pat and I would revisit pipes we’d reviewed earlier, with new attention to detail.

Fifteen pipes. Was this the inventory of the person who made them? Is that why there were several apparently unfinished pipes? There was even a preform, a core on which the entire shape had been completed except for the borehole, which had just been begun. There were also broken pipes. Were they “in for repair”? Did the pipe-maker have another use for them?

Fifteen pipes. Most pipes have a bowl, but none of these did. The pipes that we assume are finished have a cylindrically shaped protrusion atop a carefully built shoulder. What purpose did it serve? Is it an attachment point? To what would it be attached? Is this end the mouthpiece? There was no sign of use, of burning, to make the orientation obvious.

I imagine the maker. Patient. Even though steatite is relatively soft, it is still rock, hard to carve. It’s difficult to “drill” a borehole through a 7–9-inch (18–22 cm) stone using only a harder stone. No power drill. Nothing but the human hand and ingenuity. Careful and skilled, but not perfect. There was one pipe—only one—in which the boreholes begun at each end didn’t meet precisely, leaving an occluded half-circle in the middle.

Fifteen pipes. Months of work.

We assume the pipes were meant to be smoked or to create smoke. Tobacco or other aromatic substances (or both) would have been stuffed into one end and lit, although these steatite pipes showed no evidence of burning. Pipes of this type are sometimes called “cloud blowers.” In the desert, clouds are welcomed. Perhaps, though we have no information, these were not intended for personal or ceremonial smoking. On the other hand, the very small ones were surely personal smoking devices, wouldn’t you think? We cannot know with certainty.

We are privileged and honored to document and help care for these objects. We see the pipe-maker or makers and users through the haze of time, imperfectly, however much we strain. We see them through the veil of smoke that might be made by fifteen cloudblowers.

Mary Graham and Valerie Freireich reviewing just-washed objects. Image: Kathleen Bader