- Home

- >

- Preservation Archaeology Blog

- >

- Mimbres Architecture (and Tucson Neighborhoods)

(September 14, 2021)—Household architecture has always carried meaning, now and in the ancient past. Almost a year ago, I moved to a Tucson neighborhood built in the late 1950s through 1970s. The numerous repairs I’ve faced ever since are worth it to me because one of the things I love about my neighborhood is only found in older neighborhoods here—each house is different from the others. They weren’t all constructed at once or by the same builder, and generations of owners have continued to modify the houses and yards, sometimes in quirky ways.

Although I enjoy these differences, a quick drive around Tucson shows that not everyone wants such a high degree of variation. Most of our newer neighborhoods have HOA (homeowners’ association) regulations in place to ensure that owners don’t make any modifications that would cause houses to differ from their neighbors to an unacceptable degree. The amount of difference that’s considered acceptable varies, and most newer neighborhoods even have an approved list of exterior paint colors to ensure that houses fit in.

What does variation (or lack thereof) in our household architecture say about us? How does the amount of variation a social group finds acceptable, and the architectural features we allow to vary, reflect the way a society is structured?

In a recent publication, my colleagues Michelle Hegmon, Margaret Nelson, and I examined that question in the Mimbres area of southwest New Mexico. Specifically, we wondered whether there were consistent architectural differences between villages in the broad floodplains of the Mimbres Valley and the drier, more restricted farmlands of the eastern Mimbres area on the opposite side of the Black Range mountains.

One of the hallmarks of Mimbres archaeology is a lack of variation in decorated pottery. Almost all the decorated pottery in Mimbres area villages from 1000 to 1130 CE (Common Era) is Classic Mimbres Black-on-white. This is unusual in the ancient Southwest, where people generally showed social connections to surrounding groups of people by using decorated pottery imported from those areas. Although people decorated Mimbres pottery with many different images and motifs, things like design layout and symmetry were very standardized. Only a limited amount of variation was acceptable in the decorated pottery everyone used in a Classic Mimbres period village. Was architecture as homogeneous? Was the allowable variability in architecture different between the Mimbres Valley and eastern Mimbres areas?

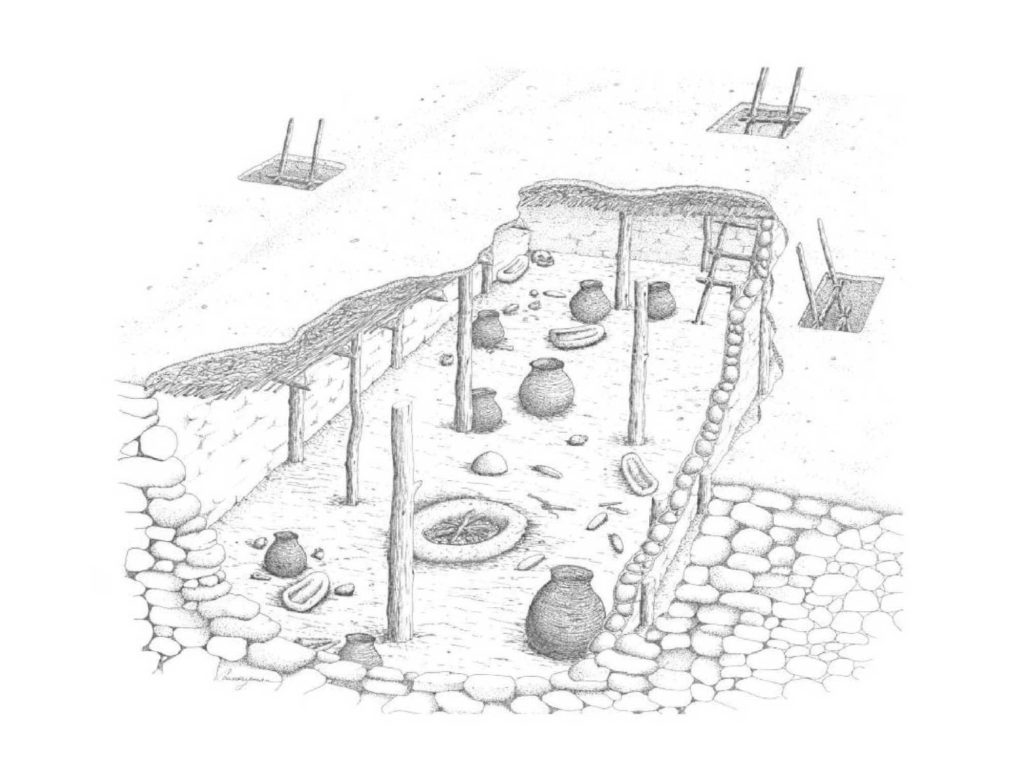

One element that might vary is room size—a variable that depends on what a room was used for and how many people used it. In both areas, people built rooms in three sizes: small, medium, and large. Medium-sized “habitation rooms” contain hearths (fire pits), and each would have been the living space for one household. A house did not have any doors connecting it to other spaces outside the household, and entrances to a house were through the roof using a ladder. Small rooms (less than 8 square meters or 86 square feet) don’t have hearths and are interpreted as storage rooms. Rooms larger than 26 square meters (280 square feet) are uncommon and were used for a variety of special purposes. People living in both the eastern Mimbres and Mimbres Valley areas constructed rooms in this same range of sizes.

Although habitation rooms were mostly in the medium size-category, that didn’t mean all Mimbres houses or households were the same. Most houses consisted of just one medium-sized room with a hearth, but sometimes a house would also have one or (less commonly) two small storage rooms connected to a medium-sized habitation room by interior doorways, an arrangement we call a “flat.”

Occasionally, people built their houses differently, presumably to reflect different family structures. In both areas, some houses consist of a “duplex”—two habitation rooms, each with a hearth, connected by a doorway. Perhaps these were built by larger households in which smaller family units each prepared their own food. And sometimes, people built “large suites” of interconnected habitation rooms and other kinds of rooms, an architectural choice that reflected more complex family arrangements for a larger household.

In other words, there was no single acceptable house configuration within each village. Different household architecture co-occurs within villages, across both the Mimbres Valley and eastern Mimbres areas.

Within people’s houses, room hearths might also reveal meaningful variation, because they would not have been seen much by people outside the household. Interestingly, people in both areas built their hearths in a variety of styles, including rectangular or square hearths lined with adobe, cobbles, or stone slabs, and round hearths lined with either cobbles or adobe. Each hearth type could either be inset down into the room floor, or could include a “collar” sticking up above the floor.

We did find one difference between areas: Rectangular hearths fully lined with neat, well-fitted stone slabs were not used in the eastern Mimbres area. In the Mimbres Valley, some hearths of this type also have rectangular slab-lined floor vaults—long narrow pits in the floor—built near them. Rooms with these floor features have been interpreted as ceremonial spaces, so it’s interesting that people in the eastern Mimbres area did not have them.

Changes in architecture over time also varied between the two areas. In the Mimbres Valley, nearly all large Classic Mimbres period villages have the remnants of earlier, Late Pithouse period villages underneath them. Archaeologists think village residents continued to live in the same locations over this time period while changing their architectural style. In the eastern Mimbres area, some of the larger villages have Late Pithouse structures underlying them, but others do not. It seems likely that fewer people lived there during the earlier time period, although we’ve also done much less research on that period.

At the end of the Classic Mimbres period, social changes and the architectural shifts that accompanied them were also slightly different between the two areas. In the Mimbres Valley, most people left the large Classic Mimbres villages around 1130. A few chose to stay for a short time in their old buildings, but began using imported decorated pottery—a choice previous generations never made. Decades later, in the Black Mountain phase, farmers began building a new style of adobe pueblo and using different pottery. These adobe pueblos were not built on top of the Classic Mimbres villages, although some were close by. It’s not clear whether or how much continuity existed between these builders and the Classic Mimbres period farmers before them.

People in the eastern Mimbres area made different architectural choices at this time. Rather than staying in their villages after 1130, a large proportion of residents moved into their former field houses (part-time residences in farming areas) and remodeled them into year-round homes. People remained in the resulting hamlets for a generation or two, but then stopped leaving architectural traces archaeologists can identify. Farmers’ residences are not archaeologically visible in the area again until many decades later.

Two patterns emerge from this comparison. One is that although people living in Mimbres villages showed a lot of conformity in some ways—like using the same decorated pottery and living mostly in medium-sized rooms with a hearth—there was also acceptable variation in how people could set up their households. Some had more rooms or differently connected rooms to accommodate different family structures, and the shapes of people’s hearths also varied. In some ways, this is reminiscent of Tucson’s newer neighborhoods, where the outsides of homes must all look alike but residents shape the private spaces (indoors and in their backyards) in many different ways to suit different family sizes, configurations, and needs.

The second pattern, which we discuss in more detail in the published article, is that although the differences between eastern Mimbres and Mimbres Valley architecture are fairly subtle, they do reflect a larger social difference between the two areas. The Mimbres Valley has archaeological evidence for an intergenerational land tenure system in which some families or lineages had greater access to the most productive land. This includes persistent use of the same villages, the same burial locations, and the same rooms and groups of rooms over time in the Mimbres Valley, as well as more highly visible ritual architecture. The subtle architectural differences in the eastern Mimbres, with less evidence for persistent places and for ritual structures, suggest a less strongly developed intergenerational land tenure system there.

Perhaps the less dense population of the eastern Mimbres area didn’t lend itself to the formation of a strong land tenure system or other lasting intergenerational differences in access to resources such as food, raw materials, or ritual spaces. Perhaps this difference also accounts for the difference in how people changed their strategies with the end of the Classic Mimbres period: It was socially easier for eastern Mimbres area families to remain in the area and move to existing fieldhouses than it was in the Mimbres Valley, where a smaller proportion of the population stayed in place at their ancestors’ homes and others left the valley altogether.

It’s an interesting possibility to think about as I move through Tucson. I can’t help but notice the subtle and very unsubtle ways in which people choose to vary the more publicly visible parts of their homes, and I think about what those differences might show or hide about the people living inside.

Author’s note: this post briefly summarizes the research in the recent Kiva article, “The Classic Mimbres Period in the Eastern Mimbres Area: Evidence from Ceramics, Architecture, and Settlement” (https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/00231940.2021.1949799) by Michelle Hegmon, Karen Gust Schollmeyer, and Margaret C. Nelson. If you don’t have institutional access, I’m happy to send you a free author’s copy (email me at karen@archaeologysouthwest.com).

Without both generous individual landowners and public research institutions, synthetic long-term archaeological research like this would not be possible. This work was supported by private landowners (including the Turner Foundation and the A-Spear Ranch), our universities, and by the National Geographic Society (grants 6980-01, 6612-99 and 52113-94) and the National Science Foundation (BCS-0508001, BCS-0542044, and BCS-1113991).

One thought on “Mimbres Architecture (and Tucson Neighborhoods)”

Comments are closed.

Very nice summary made particularly enjoyable by the comparison to current home building patterns. It enhances the sensation of discussing real people, not generalized ancestors/inhabitants.