- Home

- >

- Preservation Archaeology Blog

- >

- On Archaeology: Karen Schollmeyer

Saturday, October 16, was International Archaeology Day. When we can, we like to commemorate IAD with a blog series. This year, several members of our staff are sharing how they got into archaeology, what they thought the field was, how they think about it now—and even what they think archaeology should be.

We’ll have a new post almost every Friday through the end of the year.

(November 12, 2021)—I really like science. When I was 12, I wrote an essay detailing the many reasons I would never, ever, enter the boring, frustrating field of archaeology. Archaeology, I was sure, was the realm of hapless nerds who spent many fruitless months painstakingly searching for an ultra-specific pottery sherd or stone flake they might never find.

I simply didn’t have the patience for that kind of ungratifying labor. I wanted to become some kind of scientist instead…because I really liked science.

Thirty-some years, three degrees, and what feels like a billion spreadsheets and Word documents later, it seems I was wrong about some things. (Except maybe the nerd part, but I’ve embraced that.)

Like many people, I once had the impression archaeology was about things. Archaeology appeared to be about trying to find particular items—special rare objects that would change the way we thought about human history all by themselves. A couple of hours in the McKemy Junior High School library researching my essay for a career-exploration assignment quickly showed me that archaeology was mostly lacking in Indiana Jones-style adventure, and it failed to teach me what David Hurst Thomas has said so well: “It’s not what we find, it’s what we find out.”1 That’s true of science in general, and the archaeology I do now is science. (Sorry, 12-year-old self.)

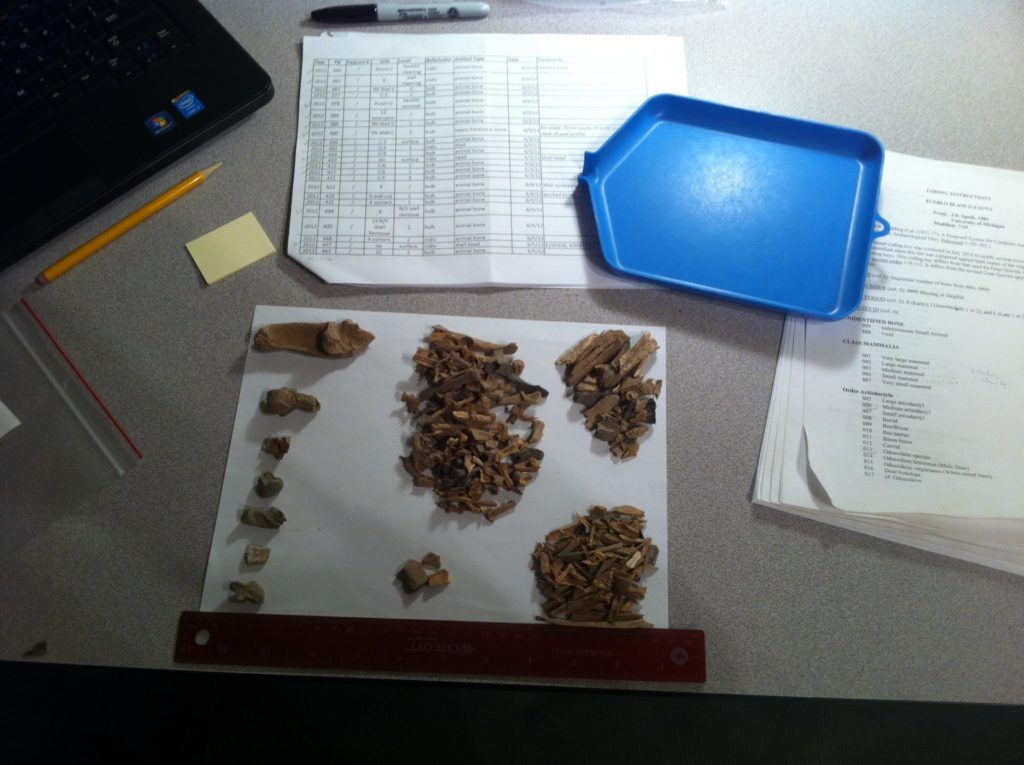

By the time I arrived at Archaeology Southwest, I was the epitome of a person who used superficially boring things to find out interesting information. As I’ve written before, there are few things less exciting than the zillionth piece of smashed deer-sized long bone shaft fragment in an assemblage that’s been sitting in a museum somewhere for years.

But when we add up all those individual pieces of not-so-exciting data, we can see exciting patterns, like how past game animal populations changed in response to the ways people’s houses and villages were spread or clustered across the landscape. We can see ways of using the landscape that let farmers hunt deer and other animals quite heavily around their homes, but didn’t deplete resources at a larger scale that would have led to extinction.

Similarly, by examining how different numbers of “boring” broken pieces of the same few pottery types are distributed across ancient villages and regions, we can see how migrants cautiously entered a new land filled with established residents who weren’t always very welcoming. We can see how these groups of people settled in together, gradually overcoming their fears to build communities that included everyone. These are things that tell us about the past, but also inspire us to work toward a better present and future.

To me, that’s what science is—examining data to learn exciting things that are not just interesting intellectual contributions to a specialized field, but also have broader relevance for making everyone’s lives better. Most grants that fund scientific research ask applicants to convince the funding agency that their work will do exactly those things. The applications are evaluated and discussed at length by a group of experts in their fields, and only the ones that make a good argument for a broader relevance for their work will be funded.

For me, archaeology is science, and learning new things that are inherently interesting and will also benefit everyone is why I love it. But…what if learning these new things doesn’t benefit everyone? What if it turns out that some of the science is excluding or even harming people? There’s a growing awareness that archaeology has a history of doing that, and readers will see that reflected in this blog series.

Archaeology and many other scientific fields have a history of excluding people, sometimes intentionally and sometimes unintentionally. One way people have often been excluded is through a lack of training opportunities. Early lab work experiences in archaeology have long been volunteer positions, which can sound innocuous until we consider who has time to volunteer and who does not. Working a full-time job while in school, caring for other family members, and juggling many other things can make volunteering for hours each week impossible. Some students simply don’t know to ask about extra opportunities—or they see no one who resembles them doing scientific work, and are led to believe there’s no space for them there. Jobs in archaeology, like most fields, tend to go to people with more qualifications, so people whose life circumstances helped them to do things like volunteer in a lab or pay to attend a field school—not to mention attend college in the first place—are the ones who most often end up in archaeology professionally.

What are we missing without diverse voices? Smart, talented people from lower-income families, people from families where few (or no) relatives attended college, and people of color are profoundly underrepresented in science in general, including archaeology. When the people whose ancestors are about to be studied are not at the table—either among the archaeologists leading the studies, or invited or consulted in other capacities—decisions are made that have negative effects on descendant communities. When people are not at the table, some of the science is missing. Our life experiences influence how we think, how we interpret evidence, and the ideas we come up with, so diverse backgrounds among scientists mean more diverse ideas, more nuanced interpretations, and better work, period.

My teen and tween daughters are starting to have conversations at home about just these topics—privileged categories of knowledge and opportunities that not everyone has equal access to. They can see differences in access to types of knowledge and support among their friends and people they know, and it bothers them. They want straightforward answers, and they are often frustrated when I tell them that if big, complicated problems had easy solutions, they wouldn’t be problems anymore.

Overcoming centuries of exclusion is a big, complicated problem, and so far the solutions we’re working on have been slow, small steps that gradually chip away at it. This can still feel frustrating sometimes, but one of the steps I feel passionately about is training a new generation of archaeologists that includes more of the people who’ve been excluded in the past. Programs like the National Science Foundation’s Research Experiences for Undergraduates (REU) program are one way to remove some of the barriers traditionally underrepresented people face. The REU program provides funding specifically for students to do research with professional mentors, so that opportunities that used to be unpaid (like lab work) or require students to pay even more (like field schools) can be offered as paid student positions.

I’ve been lucky to work with REU-funded students in various capacities over the years, including our archaeological field school, and I’ve become convinced this program is one of the best things the National Science Foundation does. Students have come up with new ideas, perspectives, and interpretations I wouldn’t have thought of, because they’re smart and their different backgrounds enable them to think differently from me, and to see the same data through different lenses.

It sometimes seems like a small step, holding the door to archaeology and research open for a few people at a time to go through as they wish. And yet—slowly but surely, over the years, some of these students have continued in archaeology, earning advanced degrees and increasingly responsible positions in cultural resource management firms. They’re at the table now, part of the group making decisions. They’ll keep moving up into positions where their insights will have more and more impact.

Archaeology needs more than a few people at the table who are able to think of unintended consequences of our actions. We need more people who have the ability to see patterns and make interpretations that someone from a different background from theirs wouldn’t think of. A few people at a time is a step in the right direction, but smaller numbers of voices can get overlooked or drowned out all too easily.

I don’t have a lot of answers, but I know we’re missing a lot of smart people who have skills and insights they’ve gained from the very backgrounds that have traditionally kept them out of science. We’re missing people who can point out more barriers that exclude people, too—barriers I don’t see very well because I haven’t crashed painfully against them.

What archaeology should be is a science that doesn’t keep people out, and that has room for lots of different people whose diverse backgrounds and life experiences enable them to see things from different angles. It should be filled with people who love working together to compare their different views, and who use their differences to build a clearer picture of scientific data, patterns, and the implications of what we learn for making everyone’s lives better. That kind of archaeology is better for human beings, and it’s better science.

And I really like science.

1 Thomas may have already penned this phrase by the time I wrote that essay, but it was pretty hard to find great source material in a place dominated by World Book Encyclopedias and a complete set of the innumerable “Sweet Valley High” novels.