- Home

- >

- Preservation Archaeology Blog

- >

- On Archaeology: Shannon Cowell

(December 17, 2021)—My mom grew up in a suburb of Atlanta during the Civil Rights movement. She rejected her parents’ revisionist Confederacy-worship and raised me with an understanding that every retelling of the past has an agenda. Encouraged by her, I took my first anthropology class, which opened my eyes to the world beyond my small town in rural Wisconsin. Anthropology seemed like a path toward understanding and liberation, a way to do something good in the world. I didn’t understand the colonial legacy of anthropology and archaeology—yet.

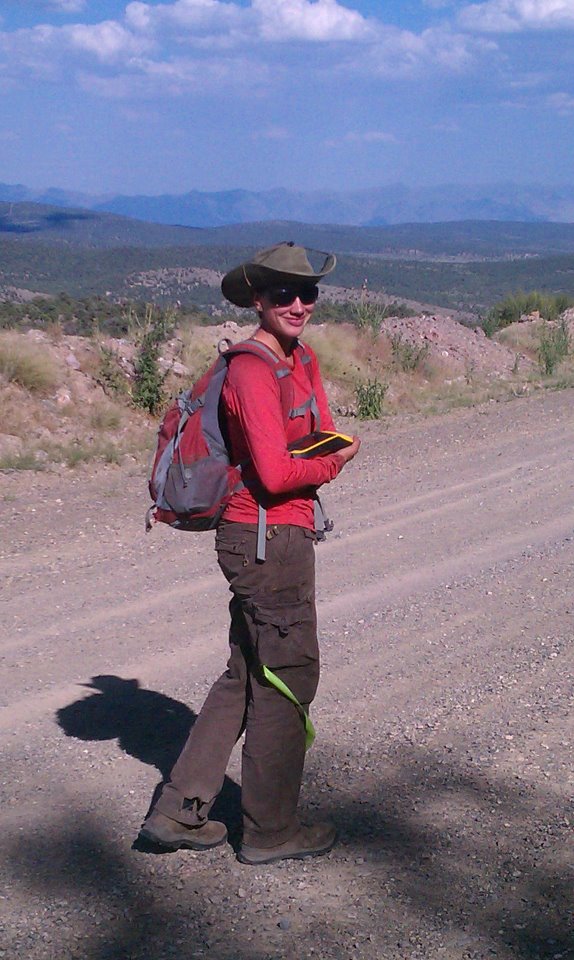

I was confused, disoriented, and totally without a plan throughout my undergraduate experience, so I enrolled in an archaeological field school on a whim. I started work almost immediately for a cultural resource management (CRM) firm and discovered how contract gigs could provide real economic independence, an elusive goal for Millennials like me who graduated during the Great Recession. I submitted my resume to every listing on ShovelBums and ArchaeologyFieldwork, gassed up my Honda Civic, and crossed my fingers.

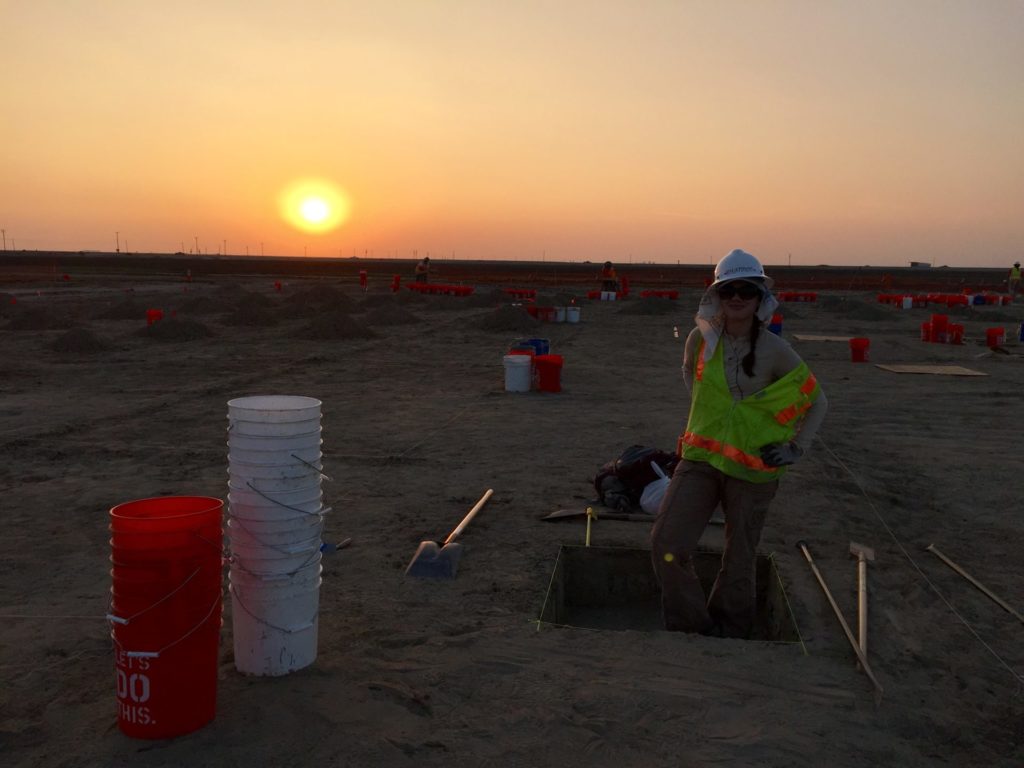

Over the last 12-plus years, I’ve worked in 20 states for about 10 different companies. I’ve waterscreened globs of rusty hull from a Civil War shipwreck in Galveston, uncovered tools made of Knife River chert at a bison kill-site excavation in northern Minnesota, and recorded 1920s cars discarded in gullies near San Diego. I’ve cooked innumerable electric-skillet dinners in sketchy motels and lost my sanity in two remote man camps (more about those below). I’ve been charged by a brown bear in Alaska and shot at twice (on purpose, I believe, on BLM land in Arizona and Oregon… go figure).

I sacrificed depth for breadth, becoming a jack-of-all archaeological contexts and a master of none. I’ve borne witness to a wide cross-section of archaeological sites, environmental issues, and political conflicts throughout the country. The plastic storage tote I use to store my camping supplies is collaged with a collection of bumper stickers protesting the very projects I worked on.

One particular pipeline project in Oregon opened my eyes to the harm archaeology’s regulatory framework (and the petroleum industry) inflicts on Indigenous communities. We were tasked with recording a specific type of feature related to a ceremony still practiced by the Klamath Tribes—and after our recording, these features would be dismantled by Elders to make way for pipeline construction. We excavated in submerged and frozen sediment, busting apart irreplaceable archaeological deposits while rock drills revved their engines right behind us. I found this painful and frustrating, and I felt powerless. I didn’t want to be part of it, but I needed the cash and the promise of a full year of consistent work.

The culture of archaeology can be an unwelcoming and challenging environment. Alcoholism runs rampant, and I carry a mixed bag of joyful and regrettable memories from rural dive bars and hotel parking lots. For some people, archaeology is a way to gain access to vulnerable young people in the isolated, permissive environment of “the field” (#metoo). White-dominated crews and cultures of harassment inhibit diversity of thought and force underrepresented or targeted people to work overtime to manage their mental health in toxic work environments.

So, archaeology already has a brain-drain problem that diverts smart and creative people to more stable fields. If we want to diversify—and we must—then all jobs, and especially entry-level ones, have to become respected, stable, and supported. I’ve been underpaid, endangered, nickel-and-dimed on per diem and mileage, and laid off with no notice by massive international engineering firms. I know the economics are complicated, especially now that I create project budgets, but we have to work together across the board to undo archaeology’s scarcity culture. Being underpaid and imperiled shouldn’t be a rite of passage. Unionize it.

In stark contrast to Skylar Begay’s blog post about his Elders, every single one of my grandparents and great-grandparents had a looting story to share with me when they learned I was an archaeologist. They told me stories about picking up raw chert in canyons in Texas, combing plowed fields for arrowheads in Missouri, and collecting artifacts from a village site eroding into the Ochlockonee River in Georgia. I think collecting Indigenous artifacts was a way for them to appropriate “localness” and affirm their connection to the land as white settlers. It was disrespect and destruction veiled in reverential fetishization. From cruelty to cluelessness, settler colonialism has many manifestations.

In my current role at Archaeology Southwest on a team that responds to Archaeological Resources Protection Act (ARPA) violations, I witness the violence of looting and graverobbing and try to contend with these ongoing effects of colonization every single day. Even though the handful of excavations I’ve participated in have all been legal, permitted projects, I believe I am implicated in the same extractive tradition. Most CRM companies work to avoid and preserve archaeological sites as best they can within the existing regulations, and most of my work has been on low-impact pedestrian surveys, but still, I’ve made a living from managing Indigenous cultural resources without much consent or input from Indigenous people. As Kyle Powys Whyte wrote, I’m still “living in the environmental fantasies of [my] settler ancestors.”

I crave accountability and real change. White archaeologists need to work to differentiate themselves from looters so that we’re more than just looters with lots of paperwork. This means repatriating stolen ancestors and cultural items, collaborating with communities on research projects, and recognizing Indigenous peoples’ rights to free, prior, and informed consent. In the future, I hope to work with and for Indigenous heritage experts, like the Tribal monitors and archaeologists I’ve worked with on CRM projects over the years, and I’d like to see these experts become more empowered and involved from start to finish.

I’d also like to see more archaeologies (and ethnographies) of whiteness, white supremacy, capitalism, and environmental violence. As we dismantle settler-colonial mythologies, we have to replace them with honest histories that critique, clarify, and heal. I’ve had a few pesky research questions about man camps bouncing around my head for years. These are isolated, gendered places associated with boom-bust resource extraction that become nodes of harm to Indigenous lands and communities. I’ve lived in them, and I’ve recorded hundreds of them on survey, I think—the whole West was and is a man camp. Our ARPA work ties into these themes; looting and graverobbing are longstanding settler cultural traditions of extraction and erasure for personal profit that can be traced back to the Pilgrims.

I hear over and over again that ARPA is toothless. The more I play pretend lawyer and learn about our justice system from my experienced colleagues, the more I fear that too many of our laws and practices are decades behind current concerns and values—especially Indigenous concerns and values. I can see a few places where ARPA could benefit from saber-toothed amendment dentures, if we’d like to stretch the metaphor to its limits. But I need to do some serious work to move beyond singing Schoolhouse Rock! off-key to myself in my office.

What I love most about archaeology is that it can help answer questions about the 99.999 percent of all human lives excluded or misrepresented by authors of written histories. I think we owe it to society to find more creative ways to bring archaeology into public discourse. For example, I had no idea that Indigenous people still lived in my home state until I took a very specific 300-level anthropology class in college, American Indians in Wisconsin. The history we learn in grade school in the United States is still deleterious, dangerous propaganda. We should focus on creative outreach and explore new mediums and audiences.

I struggle with impostor syndrome as a woman in archaeology with lots of room to grow and learn, and I also acknowledge that in many areas I am indeed a colonial impostor. In the end, everything we do should lead to returning decision-making and jurisdiction back to Indigenous people. But I think white archaeologists can justify our existence if we are aware of the agendas hidden in research and regulations, find better ways to care for communities, and stand up to the entities who want to party like it’s 1899: industries hell-bent on destroying culturally significant landscapes and the entrenched political movement deeply invested in white supremacy, deregulation, and climate denial.

2 thoughts on “On Archaeology: Shannon Cowell”

Comments are closed.

Thank you, Shannon, for telling it like it is, for saying what needs to be said out loud. It gives me hope for the future to imagine that you are not alone in your thinking and your ideals.

Wow, what an excellent essay. Your diverse experiences and values have brought you a lot of wisdom. I suspect you have found a good home at Archaeology Southwest.