- Home

- >

- Preservation Archaeology Blog

- >

- Meals, Bonds, and Paleoethnobotany

“[Humans] don’t just survive; they discover; they create. … I mean, just look at what they do with food!” – Remy, from the 2007 hit motion picture “Ratatouille”

(June 21, 2022)—An important takeaway I’ve learned during my five years of serving tables and bartending in the restaurants of Knoxville, Tennessee, is that people dine together for a range of motives, but it always results in a bond among participants. Whether it be a business meeting over lunch, a family after church, or friends grabbing drinks on a weekend night, the consumption of food and drink between a number of individuals is rarely a socially insignificant matter.

This lesson has been further substantiated by the bonds formed at this field school over lunch at the site, where conversation topics vary from general day-to-day chit-chat to debates over regional pronunciations of certain words. Essentially, eating meals together is not just eating meals together—it entails a breadth of social bonding and interaction. This is an important matter for archaeologists who seek to gain an understanding of the past beyond just material culture, as well as those who seek to apply their scholarship to current issues.

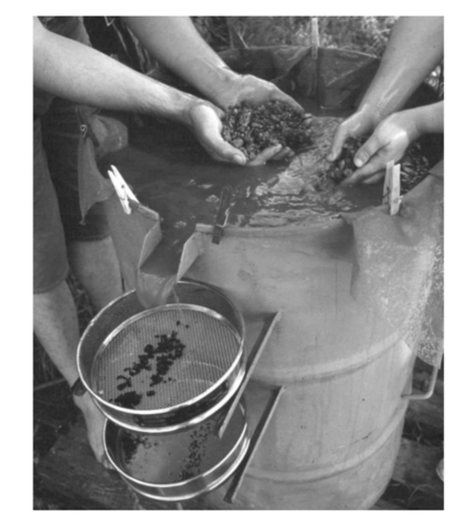

Paleoethnobotany, the subfield of archaeology focused on human-plant interaction, is one means by which archaeologists study foodways. To retrieve plant remains from archaeological sites, soil samples are taken from excavation units and put through a process known as flotation, which separates small artifacts and carbonized plant remains from the unit’s matrix. Through this process, archaeologists can infer a number of things, including sexual division of labor, social power dynamics, the general diets of past peoples, and much more. Once a flotation sample is processed, it is left to dry, then sorted by size through sieves, and finally sorted by taxa.

At Salado sites like the one we’re excavating here in Cliff, flotation samples typically contain corn, squash, gourd, cacti, juniper, pinon, and pine. Recently, we found a preserved cob of corn as well as a particularly large piece of charcoal, which will later be identified in a lab.

To me, one of the most intriguing aspects of paleoethnobotany is the implication its research has for descendent communities, whose diets have been drastically disrupted by European colonialism, industrial farming, and widening food deserts. One of the most important applications in this regard is the food sovereignty movement, which is the idea that local communities can produce and consume the majority of their own foods. This applies to Indigenous communities primarily in that the diets made available through industrial agriculture have had drastically negative health effects, resulting in obesity and diabetes rates towering above national averages.

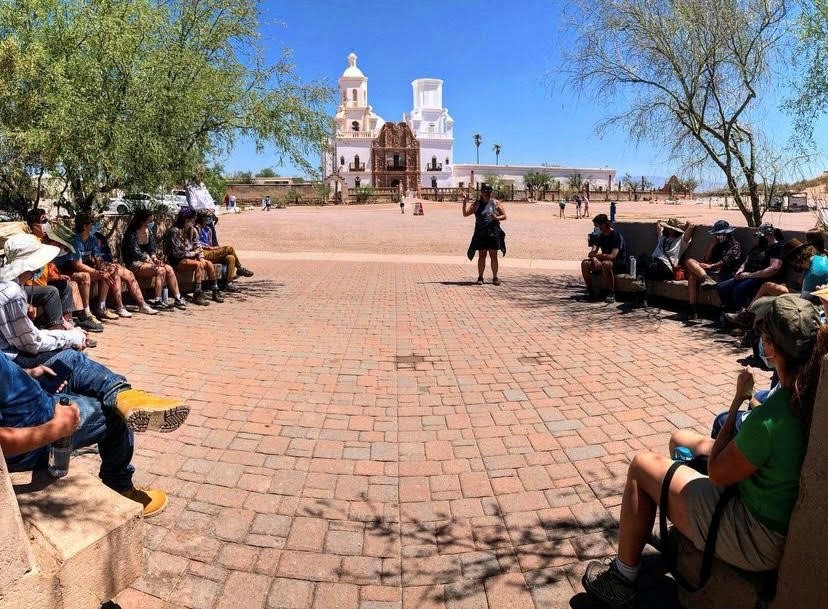

During our tour of the San Xavier Mission, our guest speaker stressed the importance of land stewardship in Tohono O’odham worldviews, which they achieve through their practice of cooperative agriculture. Other Southwestern Indigenous groups strive for food sovereignty by making cultural cuisine more available to community members through organizations such as the I-collective. Through the study of past diets, Indigenous communities are able to incorporate forms of sustainable agriculture, community ownership of food production, and overall, more culturally meaningful meals that encourage culturally important bonds and worldviews.